TRAINS, TEMPLES, AND

HORDES—GOZAIMASU! (continued)

Bruce David Wilner

July 2001

Tue 22 May Back to top

We woke up at 3:00AM after a fitful sleep, but at least I

managed to squeeze in a six-hour uninterrupted block, along with

a decent dream. "Lucky us" is my first

thought—there have been no earthquakes since we’ve

visited. Come to think of it, as many times as I’ve been in

California, there have never been any earthquakes during my

visits. Maybe I’m a good-luck talisman, or maybe such

catastrophes just aren’t that frequent, but I haven’t

even felt a tremor, and I had understood that these are quite

common—indeed, everyday—occurrences in the Japanese

archipelago.

We chitchat upon waking, since it’s too early even to

hunt for breakfast. (Though Tokyo

had enough early-bird breakfast establishments in the business

district, the same is evidently not true of this part of Kyoto.)

Cheryl notes that, though signs here are geared toward aiding

English-speaking visitors, foreigners who come to the U.S. are

essentially screwed. (We will witness this firsthand when we get

back to JFK and find all-English signage and guards barking

English instructions at bewildered Japanese visitors.) Of course,

Japan has its share of linguistic ethnocentrism: in convenience

and fast-food stores, they keep talking at us in

Japanese—seemingly out of harmless, ingrained

politeness—though they know we don’t understand a word.

My, the Japanese are such creatures of habit! Cheryl then notes

that Kyoto reminds her of Niagara Falls. The analogy is quite

piquant: a lovely place, noted for beautiful scenery (whether

natural or artificial), becomes popularized and sells out to the

tourist trade, bringing crowds, noise, and trash and leaving only

yesteryear’s memories.

I can’t believe we go home

tomorrow, and I praise God for helping us this far—with

Cheryl’s diligent planning, a fair dose of luck, my middling

(albeit enthusiastic) grasp of kanji, dynamic

gesturing, and the kindness of strangers, we have done very well.

I can only focus on the fact that my own bed lies waiting for me,

forty hours away. What a machayeh it will be (pardon my use of

an arguably esoteric Yiddish term) to crawl into our own

king-size bed with its thirteen-inch-thick mattress and

butter-soft pillows! We are now counting what remains of our

Japanese money; it isn’t much, but it should be enough to go

on. Since I’m a spendthrift, Cheryl only gives me the

equivalent of $20, keeping more than $100 for herself. Credit

cards won’t help, I think to myself—then I realize

that, even though this is supposedly a cash-only society, the

Japanese must use credit cards at some time, inasmuch as a

Persian rug at Isetan was priced at ¥1,580,000 and the largest

bill in circulation is only ¥10,000.

Since it’s now 5:00AM, we flip through various TV

channels, including the CNN Headline News in English and the BBC

news. Once again, there are nature shows set to music on several

channels. Still another channel shows the same scenes we caught

yesterday morning of a stretch of riverside freeway passing by

the Stock Exchange in downtown Osaka,

with moderate traffic whizzing past in the pitch blackness. The

scenery looks rainy, and it appears that it will rain all day

today (our last touring day) and tomorrow (the day we fly home).

The weather report (“weather” is rendered as “sky breath")

displays Celsius

temperature ranges superimposed on the cutest block graphic of

the four major Japanese islands. I’m worried about the rain

ruining my nice yellow suede Birkenstock clogs (I guess I’ve

been lucky that such sunny-weather shoes haven’t been ruined

yet), so I figure I’ll pick up some rubber flip-flops if I

can find a pair of sufficient quality to support a full

day’s walking tour. (I would have brought a pair from home,

but there just wasn’t room in the suitcase, since I had to

bring all sorts of crap that I never once used—or even

looked at, for that matter.) Now, rubber can be sweaty, but that

doesn’t matter in the rain—plus, the

flip-squeak-flop-squack noise of wet rubber flip-flops will

distract and piss off the other tourists, which should prove as

entertaining in Japan as it does in a museum or public library at

home.

displays Celsius

temperature ranges superimposed on the cutest block graphic of

the four major Japanese islands. I’m worried about the rain

ruining my nice yellow suede Birkenstock clogs (I guess I’ve

been lucky that such sunny-weather shoes haven’t been ruined

yet), so I figure I’ll pick up some rubber flip-flops if I

can find a pair of sufficient quality to support a full

day’s walking tour. (I would have brought a pair from home,

but there just wasn’t room in the suitcase, since I had to

bring all sorts of crap that I never once used—or even

looked at, for that matter.) Now, rubber can be sweaty, but that

doesn’t matter in the rain—plus, the

flip-squeak-flop-squack noise of wet rubber flip-flops will

distract and piss off the other tourists, which should prove as

entertaining in Japan as it does in a museum or public library at

home.

We head down to the station to hunt for something to eat. We

pass the usual array of vending machines and marvel again at the

variety that they offer: fruit and vegetable combinations;

peculiar teas; various brands of coffee (Wonda, Suntory Boss,

Georgia); spring water and vitamin-fortified mineral water

preparations; even the distasteful sounding Calpis and Pocari

Sweat beverages—which sell like hotcakes despite their

names. The humidity of Kyoto makes

these beverages a vital and welcome commodity. I should point out

that I never once patronized a beer vending machine, though both

Asahi and Kirin provided them. We find a kiosk open at the

station and load up on goods. The girl must have fucked up, as

I’m at a loss to otherwise explain how we could possibly

have obtained two plates of hot (microwaved)

chicken yakitori, a shrimp and noodles dish, a large

bottle of water, and an umbrella (only available in white)

for the rock-bottom sum of ¥887 ($7.10).

Heading back to the hotel before our full-day tour with

nighttime extension, we push the button that says, "Push

button to cross street," but, just like the similarly

labeled buttons at home, it does nothing. We see the most

peculiar rock video on TV at 7:00AM, in which a Japanese girl

with a long blond wig, being photographed by an immaculately

suited black man, is holding a nine-banded armadillo under her

arm as she belts out the tune. The hallway muzak is now a lame

rendition of "Angel of the Morning." Returning to the

lobby for our morning pickup, we see numerous older women in

kimonos: evidently, weddings are held frequently at this

hotel even though the place is clearly geared toward tourists. We

chuckle when we find that the Odysseys Unlimited tours ($4250 per

person excluding air fare) share the same pickup points,

buses, and destinations as the Japan Tourist Bureau tours that we

copped for $1750 per person (including air fare).

Here we go. Our guide, Toshi, will accompany us to one temple

and two palaces, though after lunch we will visit three temples

and no palaces. (Navigation among these sites is easy, since Kyoto is a planned city whose streets follow

a grid pattern—unlike the willy-nilly conglomeration that

was Tokyo.) Toshi starts off her dialogue with a historical

error, boldly declaring that Kyoto was the world’s

longest-serving seat of government (it served as capital of Japan

from 794 to 1868). Rome comes to my mind as a contender. Now, per

my calculations, Kyoto (formerly Heian-Kyo, or “peace tranquility capital"

) was the Japanese

capital for 1074 years, but Rome was capital of its empire for

1229 years (from 753 BC to AD 476). I broadcast these

dates—in addition to my frequent one-liners—making

certain that everyone in the bus can hear me and be impressed by

the handsome, wisecracking polymath with the puppy dog eyes, the soupçon

of gray hair, and the loud black-and-gold leopard T-shirt.

Presently, our Myojyo ("bright star"

) was the Japanese

capital for 1074 years, but Rome was capital of its empire for

1229 years (from 753 BC to AD 476). I broadcast these

dates—in addition to my frequent one-liners—making

certain that everyone in the bus can hear me and be impressed by

the handsome, wisecracking polymath with the puppy dog eyes, the soupçon

of gray hair, and the loud black-and-gold leopard T-shirt.

Presently, our Myojyo ("bright star"

) bus pulls up in

front of Nijo Castle.

) bus pulls up in

front of Nijo Castle.

We must place our shoes in the

rack (and our umbrellas in the basket) before entering the

facility because, once again, only socks or skin may touch the

floor.

Diversion on Japanese language:

Nijo Castle is a “national treasure"

and is so marked. In other contexts,

"national" is rendered as "nation

stand," such as in "nation stand public park"

and is so marked. In other contexts,

"national" is rendered as "nation

stand," such as in "nation stand public park"

. There are also what are known as

"quasi-national" parks, and these are somewhat

differently labeled, "nation firm public park"

. There are also what are known as

"quasi-national" parks, and these are somewhat

differently labeled, "nation firm public park"

. The group

entrance to the castle—for some reason—is

labeled "group

body entrance"

. The group

entrance to the castle—for some reason—is

labeled "group

body entrance"

.

Next linguistic diversion or

previous

.

Next linguistic diversion or

previous

Nijo Castle is beautifully

decorated. The rooms are carpeted with tatami mats,

though there is no furniture, since the emperor disliked used

furniture and threw it all away when he took ownership of the

castle in the 1800s. The Buddhist ceiling themes seem discordant.

All of the walls were richly painted by masters of the Kano family and are breathtakingly beautiful.

The themes include birds (crane, peacock, and eagle), trees

(pine, cherry, and peony), and mammals (leopard and tiger). The

leopard and tiger are anatomically imprecise, as they were

painted from skins—not from the living animals—because,

according to Toshi, “those animals do not live anywhere near

Japan.” I inform her that Siberian tigers are found in North

Korea and Manchuria (and later find—when checking my

Macdonald’s Encyclopedia of Mammals [New York:

Facts on File, 1984]—that leopards range there as well), but

she doubts my testimony. Shit, when I was six years old, I could

take you around the Bronx Zoo and point out the aoudad and the

gharial and the binturong, so don’t tell me where

fucking Siberian tigers don’t live!

Some rooms have dioramas featuring fully costumed, life-size

mannequins to show what life in the castle was like. An intricate

system of rank was in place at that time, so the emperor’s

messenger sits on a portion of the floor that is raised several

inches above the shogun’s

deck, whereas the shogun

sits above his subordinate daimyo, and so on. The dummies

show that the daimyo

wore long trousers—longer than their legs, in fact—so

that they could only shuffle along and thereby presented less of

an assassination risk to the shogun (who could clap his

hands at any time to summon the samurai who hid behind a door

only meters from the shogun’s

back). This reminds one of the scene from the Shogun TV miniseries of

Anjin’s first audience with Tokugawa. When we see a diorama

depicting the shogun’s

umpteen wives and courtesans, I remark to a Japanese couple

behind me, irome! ("erotic!"—literally,

"color eye!"

), which draws a

hearty laugh.

), which draws a

hearty laugh.

Walking outside the castle, we study the mechanism that

underlies the "nightingale floors." Each walkway is

balanced on the points of a number of iron nails that bend

slightly when their loading varies. (The creaking and squeaking

serves to warn the paranoid occupants of ninja sneaking in for a

nighttime attack—though it also woke the whole place if

someone had to sneak out for a drink of water or something less

savory.) A rock garden out back looks peaceful to me, but the

guide declares that it is considered martial by virtue of the

vertical stones peppering the pond, which supposedly summon the

image of soldiers ready to attack.

(It’s an interesting kind of "imagery" when you

must be taught what image "comes to mind." I

prefer the kind of imagery that—well, that just comes to

mind.) We are ready to attack the bus after standing out in the

rain, which has increased to a steady, miserable downpour. En

route to our next location, we hear the same three or four facts

that we have heard from every guide: Tokyo used to be called Edo; Tokyo means

“eastern capital”; Kyoto means “capital

city”; Emperor Meiji (Meiji was his reign name, his personal

name having been Mutsuhito) dissolved the shogunate in 1868; etc.

People seem astonished that I either knew these the first time or

remembered them subsequent times. Americans are so damned

ignorant: I really wish that they had bothered to read, say, a

five-page encyclopedia article on Japan before schlepping 8000

miles to visit the blessed place! Such ignorance—plus the

morbid obesity of some of them (you can spot a

high-school-educated Midwesterner from a mile off)—makes it

clear why educated foreigners stereotype Americans so

unflatteringly.

We arrive at the Golden Pavilion. I’ve seen pictures

before, and I have a poster on my living room wall that my

parents gave me. The Golden Pavilion is spectacular, even in the

spring rain (this photo doesn't begin to do justice to it), and I

can only imagine how it must look on a sunny day in late autumn,

arrayed in a fantasia of varicolored maples.

How unfortunate it is that it is also a fraud (the original

pagoda burned down and was rebuilt in 1955, and a fresh coating

of gold leaf was applied in 1988). The pagoda features three

levels: an imperial-style ground floor, a shogun-style second floor, and

a Buddhist-style top floor. Now for the de rigueur

architectural sidebar: imperial style stresses simplicity, since

the emperor need not be ostentatious; shogun style is more

extravagant, striving to demonstrate power and authority; and

Buddhist style is ornate, with intricate filigree on columns and

around windows. The whole is anticlimactically topped with a

"phoenix" that looks like a chicken to me. Just outside

the pagoda grounds, we are again set upon by a flock of

middle-school girls. They give us small origami as gifts

and are thrilled when I present my business card to them,

referring to it by its proper Japanese name, meishi. We

again take the obligatory group photo with everyone holding up

his fingers in the hip-to-be-square "Peace, brother!"

configuration.

Our last stop before lunch is the Imperial Palace (different

from its namesake in Tokyo). One

must make an appointment to come here, and if one arrives late,

entrance will be denied. I didn’t care much for the place,

since we were endlessly lining up in the rain in groups of four

while being warned that we would be arrested if we strayed from

the group. Line up over here, get drenched; line up over there,

get drenched; etc. (Some of us try to form a solid

protective cover from our umbrellas, like an ancient Roman

testudo, but the others are slow on the uptake and fail to

cooperate constructively.) The buildings are of the favored

material, Japanese cypress, and many surfaces are painted orange,

which is a joyful color in Japanese culture.(Though Japanese

culture derives in almost every respect from Chinese culture, red

is the most joyful color in China. I’m awfully glad that the

Japanese went out on a limb this time—though, admittedly, we

did note plenty of red in Japanese festive contexts.) The mundane

gardens here are considered tranquil inasmuch as they lack the

vertical stones of Nijo that, as

Toshi told us, are suggestive of soldiers.

This has been a tiring morning,

and the weather has made it all the more unpleasant. Back on the

bus, we learn some more about the emperor and his symbols. The

emperor inherits three symbolic treasures: a mirror (symbol of

the sun goddess, Amaterasu); a sword; and a jade

something-or-other. The mon, or heraldic charge, of

the imperial family is a 16-petaled chrysanthemum. Commoners are

only permitted to display a 17-petaled (and thus imperfect)

chrysanthemum; this was confirmed when I glimpsed the front cover

of a Japanese passport, which has a 17-petaled, gold-colored

chrysanthemum under the word "JAPAN" on a red

background. (No, I couldn’t count to 17 that quickly, but I

could see that the top of the mon was the center of

a petal whereas the bottom of the mon was between

petals, indicating an odd number of petals.) I almost flip out

when we finally arrive at the Kyoto

Handicraft Center for lunch, since I’m absolutely starving.

I dismount the bus and, realizing that I’ve left my

umbrella, head back toward it. Just then, the tour guide comes

running up to me with my umbrella. (This is actually the second

time in Japan that I’ve lost an umbrella and that it

graciously grew legs and returned itself to papa.) The Center

offered a very generous lunch of dubious quality: meatballs,

chicken, salmon, egg drop soup with mushrooms, lichi nuts,

and at least six more items that I’ve omitted. My, the last

time I ate a lichi nut was at a Chinese restaurant in a

very bad section of downtown Detroit in 1975. About the size of a

large walnut, the lichi has a crispy, dark brown skin that

is easily peeled off to reveal the grayish-white fruit. Its taste

lies halfway between a plum and a pearl onion. Lunch also

includes some truly odd selections, including fried onions on a

stick and a bean paste abomination labeled "Very Delicious

Chinese Cake." The salt and pepper shakers on the table are

reversed (many holes for pepper, one hole for salt). Oh, well, at

least they tried.

There are seven levels of art studios in this building.

Everybody speaks English fluently, and major credit cards are

accepted. It’s clear what’s going on here: bring us

your busloads of rich American tourists, and we will provide a

generous, mediocre-quality luncheon in the hopes that they will

buy some handicrafts. We did actually find some lovely

handicrafts to buy. At one store, we bought a beautiful set of

lacquered coasters decorated in a black and gold bamboo motif,

although we decided to forgo their samurai sword reproductions

and their dolls, which are very overpriced by comparison to the

prices at Mitsukoshi on the Ginza. We strike gold at the Uchida

("inside field"

) Art Company, where

skilled craftsmen are patiently carving wooden blocks in order to

make high-precision reproductions of classic Japanese woodblock

prints, or ukiyo-e. The artworks are printed on handmade

Japanese paper, or washi. Everyone is familiar with

Hokusai’s Under the Wave off Kanagawa, which is part

of his famous series, Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji.

(Even in The Wave, you find Mount Fuji in the distance if

you hunt for it.) We bought some Hokusai, some of

Hiroshige’s Fifty-Three Stations of the Tokaido Road, and some

well-known Utamaro works depicting Japanese ladies in traditional

court attire. It was interesting that the larger hand-carved

reproductions on authentic handmade Japanese paper cost $70

apiece here, whereas plain paper reproductions of lesser quality

cost about $140 apiece at the gift shop in the basement of the Tokyo National Museum. (I guess the

difference comes from the fortune in tolls that the truck driver

must pay to transport the prints from Kyoto to Tokyo.) Our

several purchases amounted to roughly $220, and the boss packed

them with great care and pride for the long trip home. The boss

(just like the lady at the lacquer ware shop) also stamped this

ticket that we had been given. Before we leave the facility, we

present our ticket, which qualifies us for a spin on the

“lottery” machine. I spin until a white ball pops out

and am informed that I won “fifth prize”—a choice

of either this tacky piece of crap or that goofy paper trifle. I

choose the latter and figure that I’ll throw it in the trash

as soon as nobody’s looking. However, trash cans are

extremely hard to find in this country, leading one to wonder how

it can possibly be so clean. (I think the shortage of trash cans

is the government’s way of gently persuading you not to eat

while walking, since you’ll have no place to put your trash

and will therefore have to tote your empty box of tonkatsu

with you for the rest of the day.)

) Art Company, where

skilled craftsmen are patiently carving wooden blocks in order to

make high-precision reproductions of classic Japanese woodblock

prints, or ukiyo-e. The artworks are printed on handmade

Japanese paper, or washi. Everyone is familiar with

Hokusai’s Under the Wave off Kanagawa, which is part

of his famous series, Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji.

(Even in The Wave, you find Mount Fuji in the distance if

you hunt for it.) We bought some Hokusai, some of

Hiroshige’s Fifty-Three Stations of the Tokaido Road, and some

well-known Utamaro works depicting Japanese ladies in traditional

court attire. It was interesting that the larger hand-carved

reproductions on authentic handmade Japanese paper cost $70

apiece here, whereas plain paper reproductions of lesser quality

cost about $140 apiece at the gift shop in the basement of the Tokyo National Museum. (I guess the

difference comes from the fortune in tolls that the truck driver

must pay to transport the prints from Kyoto to Tokyo.) Our

several purchases amounted to roughly $220, and the boss packed

them with great care and pride for the long trip home. The boss

(just like the lady at the lacquer ware shop) also stamped this

ticket that we had been given. Before we leave the facility, we

present our ticket, which qualifies us for a spin on the

“lottery” machine. I spin until a white ball pops out

and am informed that I won “fifth prize”—a choice

of either this tacky piece of crap or that goofy paper trifle. I

choose the latter and figure that I’ll throw it in the trash

as soon as nobody’s looking. However, trash cans are

extremely hard to find in this country, leading one to wonder how

it can possibly be so clean. (I think the shortage of trash cans

is the government’s way of gently persuading you not to eat

while walking, since you’ll have no place to put your trash

and will therefore have to tote your empty box of tonkatsu

with you for the rest of the day.)

The afternoon guides are waiting for us in the lobby of the

craft center. We choose Saito-san, whose first name I forgot,

because her English seems better than the others’. I

don’t care for her much, since she is rather officious: this

can be seen even in her excuse for a "flag"—a pink

pompon mounted on the end of a stainless steel pointer—which

stands in stark contrast to the other guides’ more upbeat

flags (e.g., Donald Duck). We are going to schlep to three

more shrines, and I’ve had it. We arrive at the Heian

shrine—largely painted in "joyful" orange—and

I decide to sit on the steps and wait, since I’m cloyed with

shrines and don’t have enough money to get back to the hotel

to rest up for our scheduled evening extension of our

entertainment marathon. The shrine would turn out to have a

lovely garden, and a nice lady snapped several on-site photos of

Cheryl, whose rotten husband stayed on the steps, resting his

feet and brain.

Diversion on

Japanese language: Heian means

"peace tranquility," with the kanji

for "tranquil"  literally showing "woman

under roof." I’m not sure by what logic they

arrived at this representation. Women figure more

logically in other kanji: "plurality of

women" and "multitude of women" represent

"quarrel"

literally showing "woman

under roof." I’m not sure by what logic they

arrived at this representation. Women figure more

logically in other kanji: "plurality of

women" and "multitude of women" represent

"quarrel"  and "adultery"

and "adultery"  ,

respectively, while my "sister-in-law" is

faithfully rendered "barbarian woman"

,

respectively, while my "sister-in-law" is

faithfully rendered "barbarian woman"

and a

"scheme" or "plan" is represented

by "woman in tree under roof"

and a

"scheme" or "plan" is represented

by "woman in tree under roof"  (you can

just see the woman hiding in the timbers hatching some

iniquitous plot), "scheme" followed by

"within" yielding "information"

(you can

just see the woman hiding in the timbers hatching some

iniquitous plot), "scheme" followed by

"within" yielding "information"

. (Maps of

tourist sites are marked either with the characters

"scheme-within picture"

. (Maps of

tourist sites are marked either with the characters

"scheme-within picture"

[which

would appear to mean "diagram" rather than

"map"] or with the more classical term for "map,"

"earth picture"

[which

would appear to mean "diagram" rather than

"map"] or with the more classical term for "map,"

"earth picture"

.)

My favorite woman-related kanji (from my admitted

chauvinist's perspective) are "marriage"

.)

My favorite woman-related kanji (from my admitted

chauvinist's perspective) are "marriage"  —which is formed from "woman"

—which is formed from "woman"  and

"(male) prisoner"

and

"(male) prisoner"  —and "wife"

—and "wife" —which most appropriately combines "woman"

—which most appropriately combines "woman"

with the

activities for which she is ideally suited, "broom"

with the

activities for which she is ideally suited, "broom"  and

"market"

and

"market"  .

Next linguistic diversion or

previous

.

Next linguistic diversion or

previous

People-watching is fun. While I’m sitting on the steps, a

young Shinto priest walks back and

forth from gift shop to gift shop, looking very chaste in his

white robe, white tabi foot mittens, and white setta.

Another tour guide happens past, leading a tour group in French,

and it strikes me as funny to hear a Japanese person speak

French, though I’m not sure why. A pair of teenage girls

dressed like harlots are leaning on a counter to scrawl prayers

on their ema before posting them on the rack. Meanwhile,

the young boy who is in their charge is running riot, trying to

break the handles off the doors of the shrine with his umbrella;

stabbing his umbrella into the notice boards; and trying to knock

other supplicants’ ema off the rack. (I didn’t

expect to see such shitty—and unchecked—behavior in

Japan.) Then, a teenage guy happens past with his girl friend.

They are so tightly coupled at the arms and shoulders that they

can barely walk without breaking their necks. The young do have

some fashion sense, it turns out: the girl is wearing Birkenstock

Gizeh thong sandals crafted in snow-white leather with brass

hardware, which are avant garde even at home.

Cheryl collects me before the next leg of our trip. I had a

nice little quiet period. Driving to our next station, I notice

that there are many Circle K convenience stores (there were none

in Tokyo), immortalized in Bill

and Ted’s Excellent Adventure as a good place to ask

passersby when the Mongols ruled China. We arrive at a Buddhist

shrine, Sanjusangendo (“Hall of Thirty-Three Intervals"

), named after the

spaces between columns through which one views the 1001

hand-carved Buddhist deities, each of which sports a distinctive

face (or so we’re told).

), named after the

spaces between columns through which one views the 1001

hand-carved Buddhist deities, each of which sports a distinctive

face (or so we’re told).

Diversion on Japanese language:

The character for "interval" is used to express not only physical

spaces or interstices, but also periods of operation of

businesses. To express "hours of operation," we

write "gate

open interval"

, which

looks repetitive inasmuch as all three characters are

based on the "gate" radical. To my surprise, I

find that the word for "image" (seen on signs

that label images of Buddhist deities) is "man elephant"

, which

looks repetitive inasmuch as all three characters are

based on the "gate" radical. To my surprise, I

find that the word for "image" (seen on signs

that label images of Buddhist deities) is "man elephant"

. I also saw "elephant"

on one of my convenience store receipts, in which

context, I’m told, it means "liquid," as

in "cash tendered." It’s easier to learn

the co-significs: I master "emperor" ("white king"

. I also saw "elephant"

on one of my convenience store receipts, in which

context, I’m told, it means "liquid," as

in "cash tendered." It’s easier to learn

the co-significs: I master "emperor" ("white king" , the king

of utmost purity), "pure" ("water blue"

, the king

of utmost purity), "pure" ("water blue"

; pardon my poetic license, by which purity is

associated now with white, now with blue), and—seen

at the fish market in Tokyo—“whale”

("capital fish"

; pardon my poetic license, by which purity is

associated now with white, now with blue), and—seen

at the fish market in Tokyo—“whale”

("capital fish"

, considerations of zoological precision

aside).

, considerations of zoological precision

aside).

Note that, even where I believe I've

found co-significs, it could just be happenstance that

the element accompanying the radical contributed the

right sound. In the preceding example, can I be certain

whether the characters "capital fish" intend

the poetic, co-signific interpretation—"the

life form that is capital among the fish"—or the

pedestrian, phonetic interpretation—"the word

pertaining to fish that sounds like the Chinese word for

capital"? Even the experts aren't always sure which

is the case, so the guiding principle is that, if

thinking about a character as a co-signific helps you

remember how to draw it, then it's a harmless mnemonic

device unless you're a historical grammarian of

Sino-Japanese.

Next linguistic diversion or

previous

We play the shoe game here as well. In order to avoid

confusion (though it’s unlikely that my bright yellow suede

clogs in a large Caucasian size will get mixed up with anyone

else’s), I place a quarter on the exposed heel of one shoe.

(I will return later to find the quarter intact.) We learn about

an archery contest that took place annually on the verandah of

the temple and about a kid who fired something like 13,000 arrows

in a 24-hour period, the majority of which succeeded in hitting

the target hundreds of meters away.

Our last stop of the afternoon is Kiyomizu-dera ("Pure Water Temple"

). The bus parks in a busy

lot, and we must haul up a steep shopping street—lined with

savvy merchants who yell "Discount!" at the top of

their lungs—to get to a huge set of steps that lead up to

the temple.

). The bus parks in a busy

lot, and we must haul up a steep shopping street—lined with

savvy merchants who yell "Discount!" at the top of

their lungs—to get to a huge set of steps that lead up to

the temple.

This must be the mountainside temple that I descried in the

distance through the window while we were eating lunch at the

crafts building.

Tell me the truth, now: Aren't these endless photographs of

temples getting boring? Is this why I paid thousands of dollars

to tour Japan? No! It's for the culture and the lifestyle.

These shrines are about as relevant to the daily life of most

Japanese as the Colonial Williamsburg restoration is to that of

the average Californian.

A mendicant on the street refuses to allow me to take his

photograph (though I later caught one

surreptitiously)—unlike the "mendicant" at Nara,

who wasted no time posing for a shot. Waiting patiently for

Cheryl to complete the tour, I observe throngs of students

(including a group of girls with matching yellow umbrellas)

enjoying their green tea and sweet potato ice cream. Hooking up

with my wife after she tours the temple and heading back

(downhill, fortunately) to the bus, I see a tengu at a

shop down the street. Now, I had thought that Tengu was

just a brand of beef jerky found in the minibar in our hotel in Tokyo, but this shop sells a large wooden

mask that looks just like the character on the beef jerky

pack—a dark red, evil-looking face with a tremendously long

nose. (Research reveals that Tengu are tall, thin

demons that wear geta, whip up tornadoes with their magic

fans, and provoke war and civil unrest to keep humanity in

perpetual chaos.) I ask the lady and receive confirmation

("Tengu?" "Tengu!"). Whatever: I

didn’t buy it. The store also sells used American license

plates, some of them quite old, others with 1999 registration

renewal stickers. I fish through them for a Maryland plate and

show it to the proprietress, loudly declaring, "My

home," in English, but I don’t think she understands.

On the bus, waiting for the last stragglers to return, the

guide warms up to me when we discover that we both speak Spanish.

We chat in Spanish about many things, including her daughter, who

is now finishing her degree at Williams College in Massachusetts.

(Even the Japanese—world-renowned for the

"excellence" of their educational system—send

students to the United States.) Switching gears from Spanish, I

ask the guide how one renders foreign syllables in Japanese

writing that the katakana seem unable to support (for

example, che). Her answer is that one combines a katakana

for the consonant (cha) with a minuscule katakana

for the lone vowel (e). (Normally, a syllable ending in –u

would be chosen to prefix the minuscule, but there is no chu

sound in the katakana—only tsu—so this case is

exceptional.) So, we see that the interpretation of a text

depends upon the sizes of the characters as well as upon

their shapes. Now, how do they make that work with a word

processor, which (in English) allows one to freely intermix

characters of arbitrary size for visual emphasis? It throws a

monkey wrench into the works, that’s for sure!

We finally arrive at our hotel right around 5:45AM, just in

time to rest up for a few minutes, brush our teeth, and wash our

faces before heading out on the evening extension, which will

include a tea ceremony, a vegetarian dinner at a ryokan,

and a traditional Japanese arts show in Gion. There is no bus

this time: our guide, Tamami, jams us into a taxi that makes two

stops (once to synchronize with another taxi, once to pick up

another couple). Miles and Delia are a pleasant, educated, chatty

British couple who once lived in Cyprus and now live in Hong

Kong. Miles is a pilot, and I find "Miles the pilot"

humorous in the same way as "I. Yankem, Dentist,"

"Dewey, Cheatham, and Howe, Accountants," and

"Hotel Costa Plente" (thank you, Three Stooges).

Our first stop is Yoshiima, a more or less authentic ryokan

in the famous Gion section. The building is narrow and

long—the Japanese term this style an "eel’s

bed"—because houses were formerly taxed based upon the

width of their frontage, just like in Amsterdam. Entering the ryokan,

we must remove our shoes, and, once again, nobody even notices

how careful I am to position my shoes toes outward, as a

gentleman should. The eleven of us are split into two groups

before dinner, due to the shortage of space: one group will tour

the facility first, then enjoy a tea ceremony (that’s our

group), while the other will do tea first, tour later.

The ryokan was lovely, with traditional, tiny rooms

carpeted with tatami mats. A glass showcase abutting a Buddhist

altar (butsudan) in one of the rooms housed the most exquisite

dolls modeling samurai warriors in full battle regalia:

which are evidently displayed on Boys’ Day to promote courage

and persistency in one’s sons, as well as dolls

depicting extravagantly masked No actors. Per superstition,

the female dolls (which we did not see) must be removed from view

promptly after Girls’ Day lest the family’s unmarried

girls wind up as unmarriageable spinsters. We did not get to see

the bath or guest rooms, which are upstairs. Of course, the

traditional appearance was marred by the bright green emergency

exit and signal red fire extinguisher signage—which, of

course, are required by law in all guest establishments. The

owner and his son chitchatted about New York, and the son, in

particular, spoke unaccented English like an American. We quickly

concluded that the recession has taken its toll on arcane,

ancient cultural institutions (a geisha evening can cost

$10,000), so the owner of a ryokan has two choices: either

sell the property to a developer (for millions of dollars) or

open up to the more affluent tourists.

We are told to wait for the soft gong sound that will announce

that the tea ceremony, or chanoyu, will begin. We pass

through an atrium—donning slippers, stepping across slippery

rocks, and holding reed baskets over our heads to avoid getting

wet (since it’s raining outside)—and arrive at the

traditional entrance to the tearoom, which is not the apparent

door, but a small square opening at floor level, about two feet

on each side. (I guess obese visitors may use the door to avoid

embarrassing situations à la President Taft in the White

House bathtub.)

We must crawl into the tearoom on our hands and knees in a

carefully prescribed manner. The purpose of the opening, we are

told, is to equalize the classes by (among other things)

preventing the samurai from entering unless he first removes his

sword and helmet. (The samurai was the highest class, followed by

farmers, artisans, and merchants—merchants last because they

were not perceived to contribute substantively to society.)

The tearoom includes an alcove decorated by a classic scroll

painted only in black and white (suiboku-ga) and a pointedly

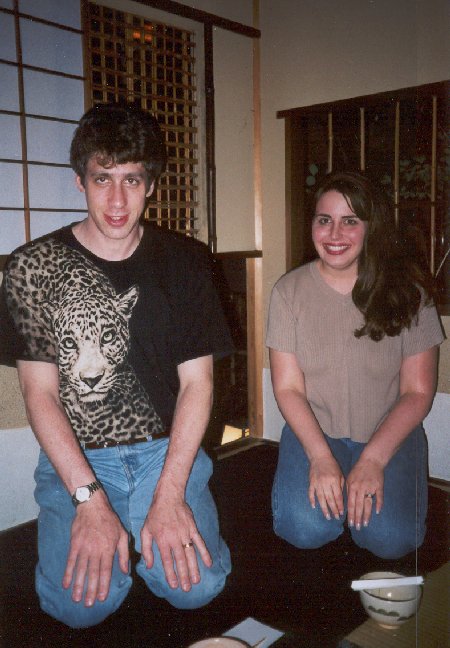

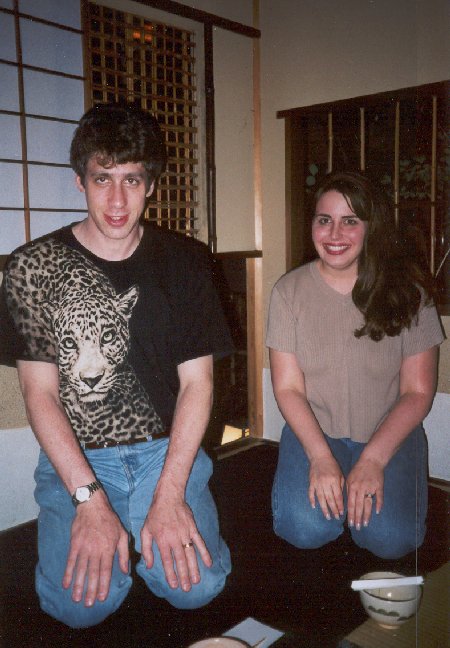

non-fragrant flower. We sit on the floor (kneeling, in actuality,

for this picture):

observing the alcove and the austerely beautiful architecture

and furnishings, and are served one-by-one by the sensei:

who has been studying chanoyu for more than thirty years. Every aspect

of the ritual is governed by a strict code: e.g., the sensei is

careful to present the teacups with the most blemish-free side facing us,

and we must rotate our cups clockwise—twice, that is—before

drinking the rich powdered tea (matcha). Its flavor is deliciously

subtle, almost spinach-like, not at all like that of the shincha

("new tea"

)

that one is served at most establishments. Tea is offered with a

"traditional sweet," served on a toothpick, which

looks—and tastes—like a brown cube of agar-agar hastily

coated with sugar. Cheryl surreptitiously shunts hers to me, but,

unfortunately, I have no one to whom to pass mine.

)

that one is served at most establishments. Tea is offered with a

"traditional sweet," served on a toothpick, which

looks—and tastes—like a brown cube of agar-agar hastily

coated with sugar. Cheryl surreptitiously shunts hers to me, but,

unfortunately, I have no one to whom to pass mine.

The dinner was all vegetarian, in keeping with Buddhist

practice. It included a fried wheat kernel foodstuff (fu), vegetable

tempura, miso soup (the finest I have ever tasted), and some

unrecognizable native plants. We learned about a card game called

hyakunin isshu—similar to Concentration® or Husker

Du®—where each poem-bearing card corresponds to a card that

relates only the final couplet of the poem. As the leader reads a

couplet, if you can recite the whole poem, you get to pick up

both cards. Talk about irony: I sit next to a young nisei

gentleman who used to live in Lefrak City in Queens—right

across the street from the cooperative where I lived for thirteen

years in the 1970s and 1980s! I have so much fun talking to Reed

(who spent several years of his childhood in Japan and now

resides in Atlanta with his wife) that I basically ignore the

tour guide as she leads us out of the ryokan into a brief

walking tour of the vicinity. We see verandahs overlooking a

canal and a shrine to the fox deity, Inari. Interestingly,

although the guidebooks said that I would "often" see

Tanuki, the badger deity, outside drinking establishments, I never

once saw him. (Perhaps he's in hiding because he's upset about being

incorrectly taxonomized: subsequent research revealed that he is

not a badger, but a "raccoon dog," Nyctereutes procyonoides.)

The only thing that attracts my interest more than my lively chat

with Reed is a restaurant that sports a curbside display of

live turtles for sale for ¥12,000 apiece. Watching their long,

serpentine necks writhe, I gather that they are a male aphrodisiac.

We have now arrived at Gion Corner for the

"traditional" culture show. I had thought that Gion

Corner was a section of the city; in fact, it’s the name of

a theater. The place is so phony—including a taped English

soundtrack that narrates the show that sounds absolutely

ancient—that even the name is foreign (Gion Kona, spelled out in katakana,

as are all lowly foreign words). Our suspicions are confirmed

when we note that the large curtain over the stage plugs

Gekkeikan and Takashimaya products in English. The phoniness does

not discourage a group of uniformed middle-school students from

attending, however.

Diversion on Japanese language:

Our English-language program is marked with two kanji

that say "brave

language"

, viz.,"language

of the brave country" (pronounced e-go). The

Japanese mechanism for naming countries and languages is

similar to the Chinese: a Japanese word is chosen that

sounds like the first syllable of the country’s name

and that has a pleasant connotation, and the word

"country" or "language" is appended as

appropriate.

Next linguistic diversion or

previous

, viz.,"language

of the brave country" (pronounced e-go). The

Japanese mechanism for naming countries and languages is

similar to the Chinese: a Japanese word is chosen that

sounds like the first syllable of the country’s name

and that has a pleasant connotation, and the word

"country" or "language" is appended as

appropriate.

Next linguistic diversion or

previous

It’s nice to have Reed sitting near us, since he provides

additional commentary that is quite enriching. One concludes that

what we’re watching—just like its soundtrack—has

been repeated day in and day out, year in and year out, since

they first discovered that tourists would pay for an

"authentic" Japanese dance and puppet show

extravaganza. We learn that the tea ceremony is unchanged since

the 1500s and that the 13-stringed koto is an extremely

difficult instrument to play. (The plectrums with which the

ladies pluck the strings do not exactly look ancient.) Halfway

through the composition, the performers are joined by what looks

like a maiko, who performs a slight dance. We desperately

needed the taped narration, as the show was so tightly

orchestrated that a fresh act was starting up while the previous

one was still going full force. In all, we see the tea ceremony, koto

players, a putative maiko dancer, ikebana (flower

arrangement), kyogen

(a comedy skit), gagaku (medieval court music with dance),

and bunraku (puppet show) in less than one hour—a

veritable three-ring circus. The wife’s camera died during

the show (just like mine did somewhere during the Himeji castle

tour), so now she believes that it’s these shitty $100

cameras—not the operators—that are to blame.

In ikebana, we learn, one must plan three chief points

of the arrangement. However, I was hard-pressed to discern a

triangle, and it is clear that, in any collection of N objects

(flowers, leaves, thorns, rhinoceroses, etc.), there are

quite a number of triangles—indeed, there are ( N3

– 3N2 + 2N ) / 6 triangles, to be precise. The kyogen comic play was

reasonably funny even though we didn’t understand word one

of the dialogue: a daimyo

(wearing the long trousers that prevent him from assassinating

the shogun)

tricks his servants into tying one another up so they won’t

drink his sake while he’s out of the estate for an affair,

but they get into the booze anyway because their fingers are free

and they have enough fractional brains to work synergistically.

The gagaku segment featured flute, drums, and a dancer

wearing a tengu mask; the music was absolutely torturously

dreadful.

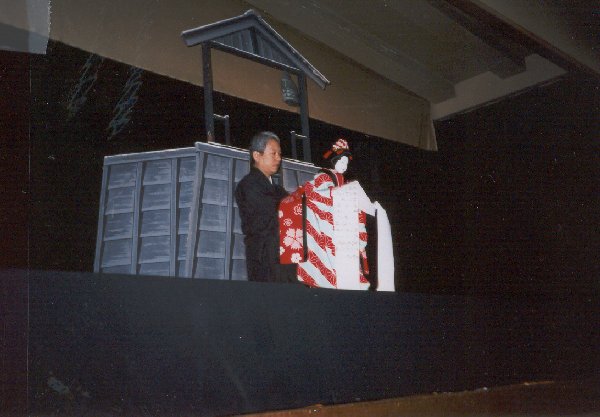

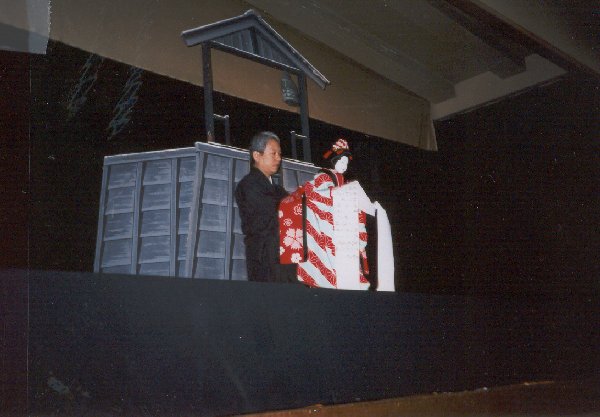

The final bunraku segment related some story about a

girl who climbs the city wall and rings the bell to communicate

something or other to her boyfriend. It was fascinating to watch

a team of three puppeteers, clad from head to foot in shiny black

but obviously in plain view, work in unison to manipulate a

single oversized puppet nearly four feet tall. Among all forms of

theater arts that I have seen, this performance was truly unique,

the four characters plus haunting musical accompaniment making

for a spellbinding composition.

That’s all, folks. On the way back, we noticed another

newfangled Japanese gadget gracing the taxi: a tiny TV mounted in

the dashboard. We got back to the hotel just in time to see

tattooed kids doing skateboard tricks (albeit not very

skillfully, with frequent, apparently painful, touchdowns on

their asses) outside the station. Ladies and gentlemen passing by

are obviously frustrated and embarrassed by this display, but

they try hard not to let the foreigners perceive it. We bought a

few cold drinks, headed back across the street to our hotel, and

fell asleep quickly. This is the latest bedtime (10:00PM or so)

that we’ve managed since we arrived in Japan.

Diversion on Japanese names: We have

seen over and over again that the Japanese name people

and things using very simple concepts from nature

that—to them, at least—sound beautiful. Nishida

("west field") and Yamamoto ("mountain

root") seem nearly as common as Smith and Jones. A

close parallel is found in Jewish surnames, which almost

always come from nature (Blumenthal = "flower

valley," Rosenfeld = "rose field,"

Steinberg = "rock mountain") if they don’t

come from the Yiddish name of the European capital

(Berliner, Moskowitz, Warshawsky, Wilner [Vilnius]) where

your immigrant ancestor was born. If we tried to take the

names of Japanese cities—as dorky as they

are—and apply a bit of creativity to map them into

something resembling familiar U.S. place names, we come

up with:

Osaka

(literally, big city) = Megapolis

Kyoto

(literally, capital city) = Capitola

Tokyo

(literally, east capital) = East Capitola

Hiroshima

(literally, wide island) = Isla Gorda

Himeji

(literally, princess path) = Queensway

Wed 23 May Back to top

We’re going home today. We woke up reasonably refreshed

at 4:30AM. I dreamed, among other things, that somebody reviewed

my Japan trip journal (in which I recorded the basis of this Web

site), calling it brilliant, free-ranging verse. I hope you feel

the same, though I’m sure you think it’s just some

guy’s hack job relating his workaday escapades in

stultifying detail.

A kids’ show airing at 4:30AM shows a woman and a puppet

singing very simple verses, many containing repeating syllables,

while hiragana transcriptions of the verses appear on the

screen. Surely they don’t expect the kids to be up at this

hour watching an educational program—or do they? Switching

channels, even while dreaming of America, we are immediately

reminded that Americans are less honest than some people, notably

the Japanese: we see Senator Joe Lieberman on CNN saying

something like, "Yes, cell phones do cause changes to

your brain tissue, but that’s not necessarily a bad

thing." I’ll tell you what, Senator: you care for your

brain tissue your way, I’ll care for my brain tissue

my way.

Arriving at the train station before the shinkansen tracks are

open, we see the clerk in the booth wiping down the counter with

a cloth—again, evidence that every Japanese regards his job

with the utmost gravity and respect. Once we are allowed into the

train, we grab a quick breakfast at the platform kiosk—in

this case, strips of smoked mackerel atop rice (for me) and

shrimp tempura atop rice (for Cheryl)—each packed, of

course, in a darling little wooden box with a tiny bottle of soy

sauce, a small packet of pickled ginger, and wooden chopsticks.

I’ve droned on enough about the shinkansen, so I

won’t belabor the point. I do notice that most of the people

on the train have just a small briefcase, probably enough for a

day trip to the capital, but we have a huge mass of

luggage—having swelled considerably from its original volume

thanks to all the gifts we bought—and seats in the rear of

the car just in front of the preferred luggage area. Although the

train is nearly empty when it leaves Kyoto, it fills up at Nagoya (the only stop

before Tokyo station). One gentleman in the front row is running

Microsoft Excel in Japanese, which strikes me as

funny even though it obviously shouldn’t. Many men are

wearing the black suits that one never sees in the U.S., and one

young salaryman across the aisle from us—who appears to be

in his early twenties—is chowing down on a Western-style

sandwich, the first I’ve seen on an actual submarine roll

rather than on surgically trimmed white bread.

We arrive at Tokyo station right

on time (of course) and must transfer to the Narita express,

affectionately known as the N’EX. A wheel just broke off our

second bag; perhaps the wife will now learn that,

when you pay twice as much, you get four times as much. The

broken wheel scraping along the floor is driving me batshit. Of

course, the Japanese never notice: they’re too lost in their

private virtual Xanadus. On the platform waiting for the

N’EX, some old guy fishes through the recycle bins to

reclaim a free newspaper, and he succeeds. I sit there scratching

the mosquito bites on my arms. I only got two mosquito bites

during the last week, but one of them is blowing up like a

balloon and I have no Benadryl. I’m still sneezing my head

off—as I have been for days—no doubt the result of the

alien plants that infest the landscape.

I decide to investigate the water fountain that is located

smack in the middle of the platform. The fountain does not have a

spring-loaded valve like an American fountain, but, instead, two

screw valves that are tightly secured. The upper one is loosened

by turning it counterclockwise (as expected), causing it to shoot

water straight upward so that you can conveniently flood your

nostrils and drown (not as expected); the lower one operates in

the same manner, but shoots downward into a basin, allowing you

enough room to stick a bottle or pail underneath. Several

Japanese businessmen heading to the airport individually pose for

a photo with my wife. This strikes me as odd until I realize that

they merely want to capture the experience of having seen a

stunningly beautiful Caucasian woman during their travels in

Japan—which, for all its people, is a very lonely place.

Diversion on Japanese language:

This one takes the cake. I recognize the kanji for

"newspaper" on a recycle bin, and the magazine

slot is next to it. The elements of the kanji for

"magazine" literally mean "nine tree chicken words scholar

heart"  .

Previous linguistic diversion

.

Previous linguistic diversion

I peek into the "green car," the first-class one, on

a passing train, and I find that—although it has two-and-two

seating instead of the two-and-three found in coach—it is

double-decker (one steps down or up from platform level to find a

seat) whereas coach is only single-level. I guess the Japanese

are trying to squeeze as many yen as possible out of their

"first class" service.

Finally, the N’EX arrives. It seems to be two minutes

early: something is wrong. It also flies straight past our

location, so we all run for the train, whereupon a uniformed

attendant promptly kicks us off and tells us to take the next

one. (Of course, I couldn’t understand what he was saying,

but his grimaces and gestures were sufficiently discouraging, and

everyone else abandoned ship, so I can take a hint.) It would

appear that this N’EX train has been split into two

pieces—a front half and a rear half—and each one stops

at precisely the designated portion of the platform.

The N’EX train is quite comfortable and is full of

foreigners. There are generous areas for large suitcases within

easy reach. The train has a map on either end that lights up with

LEDs as you make progress to show you how close you are to

Narita, which is at least forty miles outside town. I gawk at the

scenery—even though I’m quite tired of scenery viewed

from within moving trains—and see 25-story manshon;

the first free-standing gas station I’ve seen in Tokyo; and the Beatles painted in

psychedelic colors on the side of a private house, executed in

such a manner as to be specifically noticeable from the N’EX

train.

We arrive at Narita airport. A

Muslim clad from head to foot in traditional white

garb—looking for all the world like a Taliban

extremist—gives his Japanese host a hugging and kissing

farewell. This so warms my heart that I spontaneously crack the

widest smile, to which the Muslim responds in kind. The unity of

mankind is captured in our eyes: friendship transcends language,

culture, and prejudice. We head upstairs to the sizable shopping

area to eat. I am at a loss to explain why the character for

“north"  marking the north

escalator looks different from the standard character for "north"

marking the north

escalator looks different from the standard character for "north"  . We are

so tired of Japanese food that we dream of sinking our teeth into

delicious—McDonald’s. The McDonald’s upstairs

offers such oddball fare as Teriyaki McBurger and bacon-potato

pie. Also, the staff gives you a number, which you carry to your

table, and they subsequently serve you at the table. Near

McDonald’s in the shopping arcade, a duty-free jewelry shop

("avoid tax treasure stone sell shop"

. We are

so tired of Japanese food that we dream of sinking our teeth into

delicious—McDonald’s. The McDonald’s upstairs

offers such oddball fare as Teriyaki McBurger and bacon-potato

pie. Also, the staff gives you a number, which you carry to your

table, and they subsequently serve you at the table. Near

McDonald’s in the shopping arcade, a duty-free jewelry shop

("avoid tax treasure stone sell shop"

) is trying to unload

a tacky $400 Rolex knockoff, replete with three-pointed crown

logo, called a "Marshal." (I should note that the most

popular wristwatch I saw during our travels in Japan

was—guess what—Seiko.) After dining and exchanging

money at one of the numerous money exchanges (much more grandiose

than the ones at Kennedy or Dulles—and always open),

clearing customs and immigration is a snap. It is as easy to get

out of Japan as it was to get in. What an efficient, friendly,

cheerful, grateful-for-your-tourist-dollars people.

) is trying to unload

a tacky $400 Rolex knockoff, replete with three-pointed crown

logo, called a "Marshal." (I should note that the most

popular wristwatch I saw during our travels in Japan

was—guess what—Seiko.) After dining and exchanging

money at one of the numerous money exchanges (much more grandiose

than the ones at Kennedy or Dulles—and always open),

clearing customs and immigration is a snap. It is as easy to get

out of Japan as it was to get in. What an efficient, friendly,

cheerful, grateful-for-your-tourist-dollars people.

On the plane, the majority of the Japanese read comics

(I’m not sure if they’re manga), which makes me

wonder about either their literacy or the profundity of the comic

as a Japanese literary form. Other Japanese play the most unusual

video games on palm-sized Compaq platforms that I’ve never

seen before. Their menus don’t match ours—the seafood

teriyaki entrée appears on their carte as "sea fresh bowl"

, while garden salad

is spelled out gaden

saraju in katakana. (A Chinese friend of mine

would later tell me that the Japanese shamelessly appropriate

anything and everything if it helps them achieve their

purpose—but it’s hard to believe that they can’t

express the concept of salad with native Japanese words, viz.,

"vegetable assorted dinner precede cold" or some such.)

I’m noticing such things because, naturally, I’m bored

shitless by the plane ride. I’m also not sure why the long

haul eastbound takes thirteen hours—exactly as long as the

long westbound haul—since, when I travel to California, it

takes only 4:15 eastbound as compared to 5:45 westbound. Going to

Japan, we took the great circle route over Canada, Alaska, and

Vladivostok; going home, we appear to be following what looks

like a straight line on the Mercator projection, supposedly to

catch optimum tailwinds. I had the stewardess phone the captain

at one point to ask where we were, and the answer was south of

Kodiak Island. Then I asked if he saw any bears, and I got no

answer from the four-striped iceberg. Typical airline captain, a

dyed-in-the-wool asshole—just because he wears a silly hat,

and presses buttons in the manner in which he has been taught,

and earns half my income, he thinks his shit doesn’t stink.

, while garden salad

is spelled out gaden

saraju in katakana. (A Chinese friend of mine

would later tell me that the Japanese shamelessly appropriate

anything and everything if it helps them achieve their

purpose—but it’s hard to believe that they can’t

express the concept of salad with native Japanese words, viz.,

"vegetable assorted dinner precede cold" or some such.)

I’m noticing such things because, naturally, I’m bored

shitless by the plane ride. I’m also not sure why the long

haul eastbound takes thirteen hours—exactly as long as the

long westbound haul—since, when I travel to California, it

takes only 4:15 eastbound as compared to 5:45 westbound. Going to

Japan, we took the great circle route over Canada, Alaska, and

Vladivostok; going home, we appear to be following what looks

like a straight line on the Mercator projection, supposedly to

catch optimum tailwinds. I had the stewardess phone the captain

at one point to ask where we were, and the answer was south of

Kodiak Island. Then I asked if he saw any bears, and I got no

answer from the four-striped iceberg. Typical airline captain, a

dyed-in-the-wool asshole—just because he wears a silly hat,

and presses buttons in the manner in which he has been taught,

and earns half my income, he thinks his shit doesn’t stink.

We arrive at JFK right on schedule. We clear customs, noticing

that they are much more interested in our possible contact with

agricultural establishments (foot-and-mouth disease!) than

anything else and that only one sniffer beagle—without

his stylish blaze-orange vest—is on duty. After collecting

our 55-pound duffel, we must hotfoot it to the AA terminal, a

nontrivial bus ride away. Even though the plane got in at 3:20PM,

Cheryl has planned our connecting flight to BWI for 8:45PM,

figuring that clearing customs can take a while and that, if

seats are available on earlier flights, we can grab them, whereas

missing a flight and hoping for a later make-up flight is not

an enviable position in which to find oneself. Two punks—who

sport crew cuts and walk like they’ve either got brooms

stuck up their rectums or were born without Achilles

tendons—try to cut the line, and I put them in their place.

While sitting in the newly built commuter terminal area, we

talk to an American couple who had visited France but were ripped

off in a small town of everything but their passports. I would

have bought their seats on an earlier flight from them

(supposedly illegal—but slip behind a pillar and exchange a

few Franklins, and shit happens), but Cheryl decides that they

deserve the seats more than I do after their ordeal. She is, of

course, right.

It’s a zoo at the AA commuter terminal, with late

flights, cancellations, fog, and every schmuck and his brother

trying to get to Boston or Cleveland or Raleigh or Buffalo. I

could bitch and moan, but you’ve all been there before, and

we got home only ninety minutes late, so I’ll spare you the

gory details, which really aren’t all that gory. Hopping on

the bathroom scale after getting home, we realize that the food

must have been healthful even though the portions were

small—despite all the schlepping and sleeplessness, I have

lost two pounds and my wife has lost seven.

Closing Thoughts Back to top

This was our second marathon tour of a very foreign land (our

honeymoon to Israel in 1999 was the first). We could readily

perceive that we were visiting Japan at a transition point where

it is wrestling with the sharp contraction of its record-setting

economy and the imminent demise of many of its most treasured

cultural traditions. Nearly everyone we spoke to yearned in one

way or another for the "good old days." This isn’t

the same old yearning that the old always offer at the expense of

the young—this is very real: Japan only emerged from its

self-imposed isolationism after Mutsuhito took the throne in

1868, so it has charted a meteoric path to success and back.

"It is only with the heart," wrote Saint-Exupéry,

"that one sees rightly; what is essential is invisible to

the eye." I have no idea what the hell that means or how

it’s applicable to this paragraph, but it sounds terrific.

Aside from its crowding, Japan is a very livable

place—more developed, with a greater variety of goods and

services, cleaner, and safer than just about anywhere. If I

couldn’t live in the United States, perhaps I’d choose

Japan. I didn’t see extensive decay and neglect like I see

at home, though the decay and neglect were both there, just

outside official view. Of course, neither did I see the

overwhelming natural beauty that I had seen in all of the books.

Maybe it, too, is there, waiting for the discerning eye to ferret

it out from between the power lines, but where the people

actually live and work, beauty is a hard thing to come by, even

if it is characteristically treasured. The Japanese seem to

lampoon themselves in this regard: so many posters

depicted the Japanese cherry trees in full bloom—as if this

were the everyday state of affairs—though my wife and I know

from observing Washington’s Japanese trees for the past

fifteen years that they bloom for all of a week in early

April (late March if the winter was mild).

The Japanese walk a very difficult, very lonely road. There is

no peace, no privacy to be had. As crowded as I find America

becoming, I will never again consider it anything but a scarcely

developed wilderness, since I don’t have to drive very far

at all to find thousands of acres’ worth of virgin forest.

As techno-sardines, the Japanese live masterfully orchestrated

lives. They could probably live out all their days in the same

five square blocks: as soon as they die, having overdosed on

mediocre-quality sushi procured from the convenience mart around

the corner, they will be interred in that tiny cemetery right

next door to their 20-story condominium tower, only blocks from

the clatter and din of the shinkansen. Amid this painstakingly

organized demi-chaos, they have subjugated the will of the

individual to the will of the collective, though in brutally

efficient and organized fashion—like so many Borg. The

individualism of the young and the tolerance of the older are

both remarkable in the light of this overpowering socialist modus

vivendi.

Whereas we had gone to Israel in 1999 to find our roots, we

went to Japan in 2001 to conduct an anthropological study—to

try to learn how people so different from us, so handicapped by

language and manners, could come knocking on the world

leader’s door only fifty years after having been all but

destroyed. I won’t drone on and on after having woven such a

detailed écriture vérité. The anecdotes have been

presented, the truth bared; accept it or reject it as you see

fit.

Suggested Reading Back to top

In addition to the references that I've cited so far, the

following were valuable for providing both general and detailed

background information about enthralling Japan and its people and

culture. They were already on my bookshelves, gathering dust.

Bowring, R., and Kornicki, P., eds., Cambridge

Encyclopedia of Modern Japan. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 1993.

George, D. W., and Carlson, A. G., eds., Japan:

True Stories of Life on the Road. San Francisco:

Traveler's Tales, 1999.

Pictorial Encyclopedia of Modern Japan. Tokyo:

Gakken, 1986.

Thiro, R., ed., Eyewitness Travel Guides: Japan.

London: Dorling Kindersley, 2000.

Underwood, E., The Life of a Geisha. New York:

Smithmark, 1999.

My wife also bought a number of travel guides, over which she

pored late into the night for the better part of two months:

Gostelow, M., Citypack Tokyo. New York: Fodor's,

1999.

Rowthorn, C., et al., Japan. Melbourne:

Lonely Planet Publications, 2000.

Umeda, A., Kyoto-Osaka: A Bilingual Atlas. New

York: Kodansha, 1993.

——, Tokyo Metropolitan Area Road and Rail

Atlas. New York: Kodansha, 1992.

Several months later, I bought this sumptuous, twin-volume,

$250 opus, for which you may want to wait until after you

return from Japan, but which is unmatched for scope and quality

of coverage and incorporates the most breathtaking full-color

spreads:

Campbell, A., and Noble, D. S., eds., Japan: An

Illustrated Encyclopedia. New York: Kodansha, 1993.

which I followed a year after with another $75 beauty:

Baird, M., Symbols of Japan: Thematic Motifs in Art

and Design. New York: Rizzoli, 2001.

Finally, you can gather wonderful ideas about what to do with

the expensive knickknacks that you bring home from Japan—and

painlessly learn the Japanese names of dozens of household

articles—by browsing:

Rao, P. L., and Mahoney, J., Japanese Accents in

Western Interiors. Toyko: Shufunotomo/Japan Publications,

1997.

Flight Schedule Back to top

DATE / FLIGHT

|

FROM / TO

|

TIME

|

| Tue 15 May American 5160

|

Baltimore-Washington International New York John F. Kennedy

|

6:00AM 7:15AM

|

| Tue 15 May Delta 25

|

New York John F. Kennedy Tokyo Narita

|

10:45AM 3:15PM (Wed 16 May)

|

| Wed

23 May Delta 26

|

Tokyo

Narita New York John F. Kennedy

|

3:15PM 3:20PM

|

| Wed

23 May American 5095

|

New York John F. Kennedy Baltimore-Washington International

|

10:45PM 11:59PM (was 90 minutes late)

|

displays Celsius

temperature ranges superimposed on the cutest block graphic of

the four major Japanese islands. I’m worried about the rain

ruining my nice yellow suede Birkenstock clogs (I guess I’ve

been lucky that such sunny-weather shoes haven’t been ruined

yet), so I figure I’ll pick up some rubber flip-flops if I

can find a pair of sufficient quality to support a full

day’s walking tour. (I would have brought a pair from home,

but there just wasn’t room in the suitcase, since I had to

bring all sorts of crap that I never once used—or even

looked at, for that matter.) Now, rubber can be sweaty, but that

doesn’t matter in the rain—plus, the

flip-squeak-flop-squack noise of wet rubber flip-flops will

distract and piss off the other tourists, which should prove as

entertaining in Japan as it does in a museum or public library at

home.

displays Celsius

temperature ranges superimposed on the cutest block graphic of

the four major Japanese islands. I’m worried about the rain

ruining my nice yellow suede Birkenstock clogs (I guess I’ve

been lucky that such sunny-weather shoes haven’t been ruined

yet), so I figure I’ll pick up some rubber flip-flops if I

can find a pair of sufficient quality to support a full

day’s walking tour. (I would have brought a pair from home,

but there just wasn’t room in the suitcase, since I had to

bring all sorts of crap that I never once used—or even

looked at, for that matter.) Now, rubber can be sweaty, but that

doesn’t matter in the rain—plus, the

flip-squeak-flop-squack noise of wet rubber flip-flops will

distract and piss off the other tourists, which should prove as

entertaining in Japan as it does in a museum or public library at

home.

) was the Japanese

capital for 1074 years, but Rome was capital of its empire for

1229 years (from 753 BC to AD 476). I broadcast these

dates—in addition to my frequent one-liners—making

certain that everyone in the bus can hear me and be impressed by

the handsome, wisecracking polymath with the puppy dog eyes, the soupçon

of gray hair, and the loud black-and-gold leopard T-shirt.

Presently, our Myojyo ("bright star"

) was the Japanese

capital for 1074 years, but Rome was capital of its empire for

1229 years (from 753 BC to AD 476). I broadcast these

dates—in addition to my frequent one-liners—making

certain that everyone in the bus can hear me and be impressed by

the handsome, wisecracking polymath with the puppy dog eyes, the soupçon

of gray hair, and the loud black-and-gold leopard T-shirt.

Presently, our Myojyo ("bright star"

) bus pulls up in

front of Nijo Castle.

) bus pulls up in

front of Nijo Castle.

and is so marked. In other contexts,

"national" is rendered as "nation

stand," such as in "nation stand public park"

and is so marked. In other contexts,

"national" is rendered as "nation

stand," such as in "nation stand public park"

. There are also what are known as

"quasi-national" parks, and these are somewhat

differently labeled, "nation firm public park"

. There are also what are known as

"quasi-national" parks, and these are somewhat

differently labeled, "nation firm public park"

.

.

), which draws a

hearty laugh.

), which draws a

hearty laugh.

) Art Company, where

skilled craftsmen are patiently carving wooden blocks in order to

make high-precision reproductions of classic Japanese woodblock

prints, or ukiyo-e. The artworks are printed on handmade

Japanese paper, or washi. Everyone is familiar with

Hokusai’s Under the Wave off Kanagawa, which is part

of his famous series, Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji.

(Even in The Wave, you find Mount Fuji in the distance if

you hunt for it.) We bought some Hokusai, some of

Hiroshige’s Fifty-Three Stations of the Tokaido Road, and some

well-known Utamaro works depicting Japanese ladies in traditional

court attire. It was interesting that the larger hand-carved

reproductions on authentic handmade Japanese paper cost $70

apiece here, whereas plain paper reproductions of lesser quality

cost about $140 apiece at the gift shop in the basement of the Tokyo National Museum. (I guess the

difference comes from the fortune in tolls that the truck driver

must pay to transport the prints from Kyoto to Tokyo.) Our

several purchases amounted to roughly $220, and the boss packed

them with great care and pride for the long trip home. The boss

(just like the lady at the lacquer ware shop) also stamped this

ticket that we had been given. Before we leave the facility, we

present our ticket, which qualifies us for a spin on the

“lottery” machine. I spin until a white ball pops out

and am informed that I won “fifth prize”—a choice

of either this tacky piece of crap or that goofy paper trifle. I

choose the latter and figure that I’ll throw it in the trash

as soon as nobody’s looking. However, trash cans are

extremely hard to find in this country, leading one to wonder how

it can possibly be so clean. (I think the shortage of trash cans

is the government’s way of gently persuading you not to eat

while walking, since you’ll have no place to put your trash

and will therefore have to tote your empty box of tonkatsu

with you for the rest of the day.)

) Art Company, where

skilled craftsmen are patiently carving wooden blocks in order to

make high-precision reproductions of classic Japanese woodblock

prints, or ukiyo-e. The artworks are printed on handmade

Japanese paper, or washi. Everyone is familiar with

Hokusai’s Under the Wave off Kanagawa, which is part

of his famous series, Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji.