TRAINS, TEMPLES, AND

HORDES—GOZAIMASU! (continued)

Bruce David Wilner

July 2001

Sun 20 May Back to top

Today we head for Kyoto. I’m

awake at 2:00AM after a short dream. Walking to the am pm mart at

3:00AM while Cheryl still sleeps, the only thing on the street is

the occasional taxi—or so I think, until I see a guy buying

two 2-liter plastic bottles of Kirin beer. Even here there are

problems with alcoholism. Beer is also vended on the street, but

you must be twenty to buy it (though this isn’t enforced by

the machine), and, as we will be taught a few days later, sales

cease at 11:00PM (which is enforced by the

machine). I look through the large collection of Japanese comics

at the am pm, hoping to find a Tetsujin 28-go ("Iron Man 28"

—we used to

call him Gigantor when he played on American TV in the

1960s), but I strike out. Since we know that the shinkansen

platforms won’t open until 5:30AM, we content ourselves with

our old friend Shihab Rattansi on CNN news (at least it’s in

English; the other choices are French news and German news). I

also watch a Japanese chemistry ("change

study"

—we used to

call him Gigantor when he played on American TV in the

1960s), but I strike out. Since we know that the shinkansen

platforms won’t open until 5:30AM, we content ourselves with

our old friend Shihab Rattansi on CNN news (at least it’s in

English; the other choices are French news and German news). I

also watch a Japanese chemistry ("change

study"

—peculiarly

enough, not "change science"

—peculiarly

enough, not "change science"

—but akin to

the "ancient study"

—but akin to

the "ancient study"

that means

"archaeology") lesson on channel 4, an evident game

show on another station, and photos of old Japanese rural

life—set to hokey music—on yet another.

that means

"archaeology") lesson on channel 4, an evident game

show on another station, and photos of old Japanese rural

life—set to hokey music—on yet another.

We schlep our luggage to the Yamanote station and then ride to

Tokyo station—which, we have

been told, sees 3600 trains in and out daily. (We can see how the

station could intimidate people who didn’t grow up in New

York or London, but is it really worth it to pay the several

hundred dollars extra that the tour companies charge to lead you

through the station by the hand and bundle you onto the train

like a three-year-old—especially when the place is littered

with English signs?) We still haven’t seen the fabled subway

packers who use poles to tightly pack people into trains at rush

hour, costing many riders their shoes but never their

lives—then again, we haven’t visited Shinjuku station,

which is the most infamous for this phenomenon. We get off the

Yamanote line at 5:00AM and buy a pair of bento

boxes at the kiosk. The boxes hold neatly wrapped sushi,

individual tiny bottles of soy sauce, and hashi

(chopsticks). It’s ironic that, though the shinkansen is new

(opened in 1964), we must haul our huge bags up the steps to the

shinkansen platforms, as escalators are seldom to be found in

this portion of the station.

Our shinkansen arrives a couple of minutes before the

scheduled departure time. The sleek train is white with a

horizontal blue lateral stripe—unlike our old friend, the

Yamanote, which is silver with a green stripe.

The shinkansen’s seating is three on one side of the

aisle, two on the other.

The signs identify the seating choices as "aisle"

(actually, simply "path"  ), "center"

), "center"  , and "window" (literally, "side"

, and "window" (literally, "side"  —the character makes no reference to

glass). There is no carpet. The seats recline, and entire racks of

seats can be rotated to form conversational groups for four or

six persons. The luggage racks overhead ingeniously slope

downward toward the walls so that luggage won’t spill when

the train lists. Cheryl was careful to choose seats that are in

the last row of the car (behind which there is a generous area

for our large suite of luggage) and on the Mount Fuji side

(hoping for a view thereof). There are entrances at both the

front and rear of each car, and markings on the platform indicate

precisely where each set of doors will open. Every other

car has washrooms (both Japanese and Western) and a urinal with a

peculiar see-through window. I wonder about the first-class

"green car" but don’t get to see it yet.

—the character makes no reference to

glass). There is no carpet. The seats recline, and entire racks of

seats can be rotated to form conversational groups for four or

six persons. The luggage racks overhead ingeniously slope

downward toward the walls so that luggage won’t spill when

the train lists. Cheryl was careful to choose seats that are in

the last row of the car (behind which there is a generous area

for our large suite of luggage) and on the Mount Fuji side

(hoping for a view thereof). There are entrances at both the

front and rear of each car, and markings on the platform indicate

precisely where each set of doors will open. Every other

car has washrooms (both Japanese and Western) and a urinal with a

peculiar see-through window. I wonder about the first-class

"green car" but don’t get to see it yet.

We pull out precisely on time, and the conductor presently

marches past. Now, on Amtrak, the guy takes your tickets and

sticks them into a slot above your seat so that he can remember

who’s been vetted and who hasn’t. The Japanese do not

require that, perhaps because they all have the memory of

Kreskin: the conductor checks only once, gives us back our

tickets, and never bothers us again.

Diversion on Japanese language:

Why does every other directional sign say "square face"

? The answer

is that square + face means "direction" or

"toward." The washrooms are marked

"harmonious style" (literally, "rice-in-mouth style"

? The answer

is that square + face means "direction" or

"toward." The washrooms are marked

"harmonious style" (literally, "rice-in-mouth style"

)—meaning simply "Japanese

style"—or "Western style" (literally,

"Atlantic

style"

)—meaning simply "Japanese

style"—or "Western style" (literally,

"Atlantic

style"

). Something

tells me that wa (harmonious) derives from the

name Showa—Hirohito’s

reign—during which era the trains were built. (Actually, I later

learn that the use of wa derives from an archaic

name for Japan, yamato ["big

harmony"

). Something

tells me that wa (harmonious) derives from the

name Showa—Hirohito’s

reign—during which era the trains were built. (Actually, I later

learn that the use of wa derives from an archaic

name for Japan, yamato ["big

harmony"

],

which obviously no longer matches the modern pronunciation of those

characters [daiwa] and therefore properly requires

furigana to annotate it. Kanji like these that are

used only for their meaning—their standard pronunciation being

totally ignored—are called ateji; this term also refers

to the converse situation where the kanji are used solely

for their sound without regard for their meaning.)

Next linguistic diversion or

previous

],

which obviously no longer matches the modern pronunciation of those

characters [daiwa] and therefore properly requires

furigana to annotate it. Kanji like these that are

used only for their meaning—their standard pronunciation being

totally ignored—are called ateji; this term also refers

to the converse situation where the kanji are used solely

for their sound without regard for their meaning.)

Next linguistic diversion or

previous

Looking at the conductor, I realize that it is difficult to

tell the socioeconomic classes apart here. He is probably highly

educated even though he’s a train conductor: indeed, he

looks distinguished. Nearly everyone is dignified and spotless

and has excellent posture. They are Japanese, man, and that means

pride. I’d be willing to bet that, should the national

anthem start playing, they’d all burst into tears.

Most of the Japanese are sleeping on the train, but two

businessmen are eating Western-style food. At least, it’s

their version of Western-style food that, like many other

perceptions of the West, is about thirty years behind the times.

Specifically, the food consists of an unidentifiable sandwich on

lowly white bread, from which all of the crust has been neatly

trimmed—the way I insisted my mother prepare my peanut

butter and jelly sandwiches when I was four. The gentleman in

front of us asks us, "May I please recline my seat?"

before reclining his seat. That would never happen in America. We

are soon reminded of the ubiquity of smoking when the door to the

next car opens and a smoky miasma that could choke a herd of

elephants wafts in.

Through our windows, we get a quick survey of the

overwhelmingly ugly, immense Tokyo-Yokohama

conurbation. We see houses and manshon (high-rise

condominiums, typically twelve to twenty stories) along the

tracks. It seems peculiar to build a luxury high-rise right next

to tracks where trains whiz past at 100+ mph all day and night. We

are really wondering how these encyclopedia and magazine

photographers manage to snap pictures of such stunning natural

Japanese beauty, since we were to see no countryside at

all—and not much beauty—for the entirety of our

330-mile ride from Tokyo to Kyoto.

Throughout the ride, a uniformed kid with a silly hat hawked

drinks, candy bars, ice cream (sweet potato or green tea

flavor—never chocolate), and gift boxes of dreadful

bean-based Japanese confections called wagashi.

(They are indeed odd: I understand that one favorite, called kohakukan-ume,

is a whole plum coated with translucent bean "jelly"

and dusted with flakes of gold leaf. I put "jelly" in

quotes because, to me, jelly should be based on something

delicious, like strawberries or grapes. I always avoid

dessert at Asian restaurants back home; now we see why!)

We are hoping for a view of Mount Fuji, or Fujisan

. Is that

it? I think so. No, wait a minute: I think it’s that

mountain over there. All of this speculation ends abruptly when

we happen upon Fuji. There can be no mistake. This magnificent

snow-capped volcano fills the entire sky. Though the vistas have

largely been spoiled by power lines, this isn’t the case

here (probably because power lines don’t reach the

12,388-foot level). The gentleman in front of us tells us that we

are quite lucky to obtain such a fine view of Fuji, since

it’s usually shrouded in mists and fog. (Of course, the

pictures in books show empty fields near Fuji, not suburbs. They

must have been taken from the rural north of Honshu, not from the Tokaido [“Pacific

Way,” literally, “Eastern

Ocean Way"

. Is that

it? I think so. No, wait a minute: I think it’s that

mountain over there. All of this speculation ends abruptly when

we happen upon Fuji. There can be no mistake. This magnificent

snow-capped volcano fills the entire sky. Though the vistas have

largely been spoiled by power lines, this isn’t the case

here (probably because power lines don’t reach the

12,388-foot level). The gentleman in front of us tells us that we

are quite lucky to obtain such a fine view of Fuji, since

it’s usually shrouded in mists and fog. (Of course, the

pictures in books show empty fields near Fuji, not suburbs. They

must have been taken from the rural north of Honshu, not from the Tokaido [“Pacific

Way,” literally, “Eastern

Ocean Way"

] shinkansen tracks.)

We chuckle at the thought of the other tourists who spent an

entire day driving to Fuji and hiking up its slopes. No way on

earth did they enjoy the stunning view that we did.

Unfortunately, the camera does not capture subtle contrasts and

shadows quite as well as the eye.

] shinkansen tracks.)

We chuckle at the thought of the other tourists who spent an

entire day driving to Fuji and hiking up its slopes. No way on

earth did they enjoy the stunning view that we did.

Unfortunately, the camera does not capture subtle contrasts and

shadows quite as well as the eye.

For hundreds of miles, we see continuous housing, factories,

tiny farms, greenhouses, the occasional rice paddy, then a

high-rise manshon, with only the roofs offering any hint

of japonaiserie. People are working in the rice paddies,

occasionally with flame throwers. Interestingly, we haven’t

seen any livestock at all. The cyan construction equipment

(it’s typically yellow at home) is an interesting twist. We

also see green tea fields, snug little orchards of wasabi

bushes, tiny mountainside cemeteries, and a mountaintop sign on a

particularly ugly suburb—even uglier than York,

Pennsylvania—that proclaims "Chrysanthemum

River Ward"

with the utmost pride. I sneeze, and a lady stares at me in

horror. The Japanese have a real problem with other persons'

emissions, but what am I supposed to do?

with the utmost pride. I sneeze, and a lady stares at me in

horror. The Japanese have a real problem with other persons'

emissions, but what am I supposed to do?

It is clear that there is no zoning here at all. Even in the

city, you will find a rice paddy between two factories; a

high-rise next to a farm; a small cemetery between two

high-rises. It is absolutely bizarre. The Japanese just build,

build, build without regard to any classical sense of aesthetics.

They certainly cherish aesthetics, but aesthetics have had to be

subjugated to the interests of practicality in this tiny country

that has twelve times the average population density of the

United States. Since 70% of Japan is so mountainous as to be

uninhabitable, the population density of the the inhabited

regions is something like forty times that of the U.S. I could

ask, if the Japanese are such a nation of Einsteins, why are

their islands so gravely overpopulated?

We arrive in Kyoto. Kintetsu

station is immense and has an integrated eleven-story shopping

plaza with many shops, but the design is rather poor—you

must walk up and over and down to avoid going through train

gates. Walking down the steps to the street level, I notice the

distinct odor of urine, though Cheryl tells me I'm imagining

things. This is not as clean as Tokyo. Coin lockers outside the

station depict a mother duck and her offspring waddling

along—again, evidence of the Japanese flair for most

peculiar advertisements. We haul our luggage across the street to

the New Miyako hotel (again, Cheryl has chosen an outstandingly

convenient location: this is the nerve center of all Kyoto tours

for every tour company)—while construction workers point at

my wife and say shojo

(beautiful girl). Our room is not yet ready at 9:30AM, so we

leave our bags with the bellwoman (not a bellman!) who handles

the bags with the strength of a sumo wrestler. I call her rikishi

and get a big laugh.

People-watching in the station, I note that the Japanese are

indeed short—though, now and then, some lanky boy reaches

the six-foot-three level, which is about as stratospheric as they

get here. I also see one midget in the Kyoto station, and throughout our trip

we’ve already seen a handful of wheelchairs and one Down

Syndrome sufferer—a sobering reminder that tragedy is

everywhere and that God makes all men as He sees fit.

Cheryl had wanted to catch the

opening ceremony (at 10:00AM) of a department store in Tokyo. We

missed this performance in Tokyo, but we will get to catch the

opening of Isetan here. At precisely 10:00AM, the

doors open, and the entire staff bows and offers "irasshaimase."

We are first in line, so we bear the brunt of this assault. Each

time we pass another staff member, we receive another bow and

another welcome. It gets borderline ridiculous when, as soon as

we enter a new department, the Japanese staffers bow and scrape

yet again. Testing out the free food theory anew, we discover

that, just as at Mitsukoshi, only the vegetables are free: you

must pay for flesh. We had read in one of our tour guides that Osakans go bust on food but Kyotoans on

clothing; perhaps this is true, as we have yet to be impressed by

the food here in Kyoto. The shrimp tempura that Cheryl bought at

the department store is so heavily breaded—like Kentucky

Fried Chicken; nay, like Long John Silver’s chicken strips—as

to be nearly unacceptable. It’s harder to find our way

here, since people don’t speak English as well or as often

as they do in Tokyo. Also, it is crystal-clear that this city is

a tourist rip-off spot: we see shoji for seventy

bucks here that we could have bought for thirty in Kamakura.

Our room was ready by noon. We drew room 863 on the eighth

floor. The room was larger than in Tokyo,

but the toilet had only one flush mode. I was disturbed to find a

hair wedged between the bathtub and the sink and (the next day)

another hair—perhaps it’s mine (does that mean they

didn’t change the sheets?)—between my pillow and

mattress. Looking out the window, I conclude that the five-story

pagoda a few blocks away to the southwest must be the Toji shrine

where Cheryl wants to hunt for antique kimonos and accoutrements

tomorrow morning. Though we had a view of a shinkansen track, the

room was to be pretty quiet until the 3:00AM train thundered

along. Like the station, our room reeks of overt tourist

orientation: English signs predominate, and the Gideon bible is

in English, with Japanese text an apparent afterthought. However,

the décor is an attractive, subdued pink with blond wood

fixtures (like in Tokyo), a minibar (like in Tokyo), and a

decorative frieze with a plum/apricot/cherry blossom motif. It

also includes extra pillows and rheostats on every lamp. Opening

the dresser drawer, we find that the yukata here

has the hotel’s name, and the toilet sandals are grandma

scuffs, not grandpa cross-straps like we had in Tokyo.

Diversion on Japanese footwear: Three

types of thong sandals constitute the spectrum of

traditional Japanese footwear: the straw-soled unisex zori;

the leather-soled men’s formal setta; and the

wooden-soled unisex geta, mounted atop two

horizontal crossbars that elevate the sole several inches

above the ground for ease of walking in muddy terrain.

Men’s sandals have black straps (except for setta,

which have white straps) while women’s have colored

straps. Though setta must be worn with split-toed tabi

socks (foot mittens, as it were), zori and geta

may be worn either with tabi or without, the

latter seemingly predominant. Although we saw geta

for sale, we did not see anyone wearing them, though we

did see zori and setta—as well as

Western-style, rubber-soled flip-flops on younger folks.

We are out on the street again but must return shortly to meet

our Nara tour group. We pass a Honda (vice Acura) Vigor

and a Honda (vice Acura) Legend. (Though popular in North

America, Honda is not a popular brand of automobile here

in Japan.) We are spending lots of time enjoying the signs (at

least I am). Torturing meaning out of written Japanese is like

solving a challenging blend of cryptograms and rebuses.

Diversion on Japanese language:

I have seen umpteen words for "store": "house" , "exchange"

, "exchange"

, "merchant place"

, "merchant place"

,

"shop"

,

"shop"  , "market"

, "market"  .

I have also seen several terms for city, including

.

I have also seen several terms for city, including  and

and  . I have

more fun trying to find co-significs (or apparent

co-significs), which make up only 10% of the kanji.

I discover that a lamp is a "fire post"

. I have

more fun trying to find co-significs (or apparent

co-significs), which make up only 10% of the kanji.

I discover that a lamp is a "fire post"

and a

limousine is a "people rail" (actually, "name rail"

and a

limousine is a "people rail" (actually, "name rail"

). More

context dependencies are evidenced: child means

"little" in "little boy" and

"little girl" but is seemingly used as an

honorific in "gentlemen’s" and

"ladies’" (actually, "man-little usage"

). More

context dependencies are evidenced: child means

"little" in "little boy" and

"little girl" but is seemingly used as an

honorific in "gentlemen’s" and

"ladies’" (actually, "man-little usage"

and "woman-little usage"

and "woman-little usage"

). The to

in Kyoto

(which means “large city”) is pronounced “Miyako"

). The to

in Kyoto

(which means “large city”) is pronounced “Miyako"

when it

appears on the side of our hotel. A bank is a "silver go"

when it

appears on the side of our hotel. A bank is a "silver go"

and mixed

fruit (as in mixed fruit yogurt) is "fruit objects"

and mixed

fruit (as in mixed fruit yogurt) is "fruit objects"

. A newspaper is a "new hear"

. A newspaper is a "new hear"

, which seems

generic enough to mean any number of things. An emergency

exit—even though there is a unique word for

emergency—is the most unimportant-sounding "not usual opening"

, which seems

generic enough to mean any number of things. An emergency

exit—even though there is a unique word for

emergency—is the most unimportant-sounding "not usual opening"

. (I am at a loss to explain why the Japanese

made the evident minor alteration to the Chinese version

of the character signifying "not "

. (I am at a loss to explain why the Japanese

made the evident minor alteration to the Chinese version

of the character signifying "not "

.) Oddest of all is that "occupied"

is rendered as "convenient usage middle"

.) Oddest of all is that "occupied"

is rendered as "convenient usage middle"

. The

Japanese do not express thoughts the way we do. We

learn words, plus rules for combining parts of

speech into sentences; they learn combinations of

words that express specific abstract concepts. This

medium offers nothing approaching the expressive range of

English. How could such a technological giant muster

itself on this preposterous basis?

Next linguistic diversion or

previous

. The

Japanese do not express thoughts the way we do. We

learn words, plus rules for combining parts of

speech into sentences; they learn combinations of

words that express specific abstract concepts. This

medium offers nothing approaching the expressive range of

English. How could such a technological giant muster

itself on this preposterous basis?

Next linguistic diversion or

previous

Back in the hotel, my suspicions that this is a

hotel of, by, and for tourists are confirmed: when I ask

"What’s this thing in the minibar?" (only to end up

accidentally buying it) and call the front desk to cancel my twenty-dollar

Chivas Regal "purchase," they already know that I withdrew a Chivas

Regal—though all I told them was that I wanted to cancel an

item. Studying the room more closely, I discover a

"balcony" that is barely large enough to plant a single

geranium. The windows open to the street with no screen, which is

out of line with the safety-consciousness (fanaticism, even) that

we have seen, e.g., fire extinguishers anywhere you could

fit a red-armored mouse. I turn on the TV and see something

uniquely Japanese: a comedy variety show whose characters include

a sushi chef; a man sporting lipstick and a bra; and a policeman.

They are hanging out at a waterside resort and are engaged in

some zany slapstick, replete with throwing packages and dishes at

one another.

Our tour leaves promptly for the temples and

deer park of Nara at 1:40PM. The tour organizers give each of us

a Bambi sticker to wear on our shirts. I’m getting cloyed on

shrines, truth be known, but there’s a huge Buddha and the

world-famous deer park, so I bite my tongue. Our female guide is

Haruko. The suburbs of this city, more spacious than the

(nonexistent) suburbs of the capital, have real gas stations that

actually occupy land, made conspicuous by flashing red-on-black

LED signs that advertise the prices of gasoline in yen per liter

(three to four dollars per gallon is the average). As each car

stops at the gas station, a team of three attendants lavishes

care on the vehicle. We also see garden apartment complexes that

are closer to American than anything we’ve seen so far. A

few miles outside Kyoto,

we find ourselves in honest-to-goodness countryside, with large

tracts of lightly developed or undeveloped land that even include

virgin bamboo forest.

Arriving first at the

massive Todai-ji shrine—the world’s largest wooden

building—we learn that a Buddhist shrine is never completed

because there’s nowhere but downhill to go from perfection.

The entrance to the

shrine is protected by Unkei’s renowned pair of giant

Buddhist guardian deities (nio, or "virtuous kings"

) brilliantly sculpted in wood—one saying

"ah" and one saying "om" (the first

and last letters of the Sanskrit alphabet, a combination akin to

A—W in Christian symbolism).

) brilliantly sculpted in wood—one saying

"ah" and one saying "om" (the first

and last letters of the Sanskrit alphabet, a combination akin to

A—W in Christian symbolism).

The colossal bronze

Buddha in the heart of the temple is awe-inspiring. One of the

wooden columns exhibits a tight slit, precisely the width of the

sculpted Buddha’s nostril, through which one crawls; the

slit has some vital significance or other, but I wasn’t

paying attention. Again, thousands of middle school students from

all over Japan make the trip nearly unbearable, since an 80°F

day plus throngs of people equals a 100°F day. We try to imagine

how the temple looked before all the gold leaf was weathered off.

En route to the shrine, I hand ¥30 to a

monk with a begging bowl; I hope he was real, not just some

clever character preying on tourists. I start to wonder, since I

recall that his bowl was empty except for my three coins.

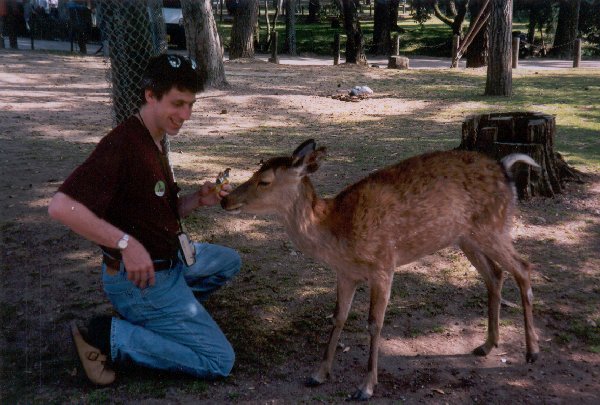

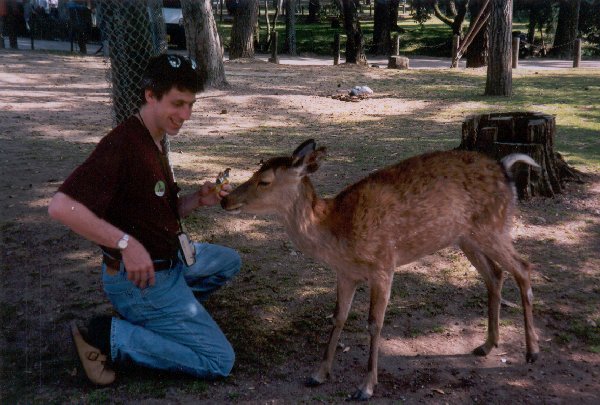

Outside the Todai-ji shrine, we pet and hug the cute

deer, which are called shika. They

are finger-trained and supposedly will rush over to you as soon

as they see you buy crackers at the omnipresent vendors’

stalls. Many bask in the sun in cliques of three to five animals.

One older sweetheart has a cataract. I figure that, since deer

eat apples and also the standard Todai-ji crackers, they might enjoy my Fig

Newtons®, and I am not disappointed: they gobble them up (better

for them than toilet paper, which they also eat—with

gusto—if the bathroom doors are left unclosed) and pose for

adorable photographs.

Of course, you must

watch out for their feces, which is everywhere.

(Speaking of feces, the bathrooms here are marked benjo

["convenience place"

]—which

is considered more than marginally gauche—rather than

"honorable hand-washing room" [o-tearai],

which is how the signage read in Tokyo. Now, though the books say that benjo means "convenience place," I happen to know

that the first character is overloaded with many

meanings—not the least of which is [conveniently enough]

"feces.") Thank goodness it isn’t raining today,

as it’s supposed to do tomorrow, lest the deer and their

"convenience" stink to high heaven!

]—which

is considered more than marginally gauche—rather than

"honorable hand-washing room" [o-tearai],

which is how the signage read in Tokyo. Now, though the books say that benjo means "convenience place," I happen to know

that the first character is overloaded with many

meanings—not the least of which is [conveniently enough]

"feces.") Thank goodness it isn’t raining today,

as it’s supposed to do tomorrow, lest the deer and their

"convenience" stink to high heaven!

Why are the deer so small, even smaller than

the axis deer (chital) from which they’re descended? The

answer is that, every autumn, the priests cut the males’

antlers amid much ritualized spectacle. This is not a good thing

from the eugenic standpoint, since antlers guarantee that only

the strongest, most fit males will be permitted to breed. With

all males equalized antler-wise, every dorky buck gets to breed,

and—since the population is limited—the hardiness of

the species declines over centuries of such intervention. These

deer are so small. I tell our guide that, at home, we have

deer weighing over 100 kilograms that are frequently hit by

suburbanites’ cars, and she can scarcely believe my

testimony.

We now head to the Kasuga shrine, where we see

the standard Shinto

priests and a variety of very ancient trees (some 700 to 1000

years old). After our tour of Kasuga—which also takes us

past a humorous sign that warns of one to avoid aggressive stags

during the mating season—we end up switching buses for some

reason or another to head back to Kyoto. We sit baking in

traffic, passing the prefecture government complex and gawking at

more peculiar cars (including the Toyota Ariel, Toyota Bluebird,

and Nissan Laurel Medalist—the last of which sports an L

logo that almost looks like the one on our Lexuses). We also pass

a Ferrari. It dawns on me that I don’t think I’ve seen

a car more than five years old. I’m not sure why: maybe cars

are legislated off the road when they start to burn uncleanly;

perhaps the Japanese are obsessed with owning new, shiny things;

perhaps they love to blow money on status symbols; or it could be

that they simply take pride in caring meticulously for their

machines, whether they fit in a pocket or in a garage. (My

Chinese friend tells me that the explanation is that the Japanese

sell their cars to the Chinese as soon as they show any wear and

tear.) All I know is that it’s a delight not to continually

stumble across revolting-looking jalopies belching out black

clouds, driven by Hispanics, and featuring a mismatched rear door

and a trunk lid in yet a third color. Our new guide, Kazuko, is

trying to embark on a lecture about the Japanese business world,

but an Indian couple’s young child won’t shut

up—which ruins the tour for all

of these nice, patient customers who paid an arm and a

leg—so I chastise the mother, calling her a sudra,

and the bus is suddenly as quiet as a tomb. Here is what we learn

from Kazuko:

The Japanese salary structure is narrow

regardless of occupational specialty. Whether you are a

university teacher, a tour guide, a bus driver (crisply uniformed

and white gloved, of course), or an engineer, you will earn $50K

in your prime and $90K when you retire. Nowadays, if you can earn

$100K at the age of forty, you’re doing well enough to

attract attention. The life of the office worker is one of

patience; striving to be virtuous; and consideration. If one

wishes to leave the office after only ten hours’ worth of

work, one must apologize to one’s colleagues for leaving

them to shoulder the burden. At least one no longer suffers the

drudgery of an extra half-day’s work on Saturday: like their

U.S. counterparts, Japanese professionals now enjoy a five-day

workweek. The salaryman’s life is shockingly restricted, so

Kazuko’s friends envy her freedom. Though food didn’t

seem outrageously expensive, a small apartment rents for $2500

per month and a seat at the movies costs $15.

Kazuko turns her attention to the mysterious

world of the geisha that has been popularized in recent

literature. A mature geisha is a geiko, and a

geisha-in-training is a maiko ("sweet little hemp

clothes girl," literally, "hemp clothes little"

, though the books

translate it as "dance girl"—which I learn later from an

airport security officer whose given name is Maiko, though subsequent

research reveals that, more than likely, either her name was

paronomastically homophonous or her command of Japanese etymology was

weak). There are only 200 geiko now, averaging in their late

fifties, and only about twenty maiko. The recession has

hit hard: most men cannot afford to pay many thousands of dollars

to be entertained by geisha at a traditional teahouse, or ryokan

(which is not to be confused with an upscale restaurant, or ryotei).

The geiko’s kimono costs ¥5,000,000, or forty

thousand dollars. Ironically, it is difficult for the untrained

observer to distinguish a geiko’s kimono from an

ordinary well-to-do woman’s formal kimono. Nowadays, many of

the maiko seen at temples are fake, as there are thirty or

so studios that will doll up a young lady to look like a maiko

for a quick $200. In the olden days, maiko began their

training at age six on the sixth of June (666 is lucky in Japan).

Since she is only permitted to visit the beauty salon weekly, the

maiko must sleep on an extremely uncomfortable wooden

pillow with a padded, U-shaped depression in order to preserve

her gorgeous coiffure.

, though the books

translate it as "dance girl"—which I learn later from an

airport security officer whose given name is Maiko, though subsequent

research reveals that, more than likely, either her name was

paronomastically homophonous or her command of Japanese etymology was

weak). There are only 200 geiko now, averaging in their late

fifties, and only about twenty maiko. The recession has

hit hard: most men cannot afford to pay many thousands of dollars

to be entertained by geisha at a traditional teahouse, or ryokan

(which is not to be confused with an upscale restaurant, or ryotei).

The geiko’s kimono costs ¥5,000,000, or forty

thousand dollars. Ironically, it is difficult for the untrained

observer to distinguish a geiko’s kimono from an

ordinary well-to-do woman’s formal kimono. Nowadays, many of

the maiko seen at temples are fake, as there are thirty or

so studios that will doll up a young lady to look like a maiko

for a quick $200. In the olden days, maiko began their

training at age six on the sixth of June (666 is lucky in Japan).

Since she is only permitted to visit the beauty salon weekly, the

maiko must sleep on an extremely uncomfortable wooden

pillow with a padded, U-shaped depression in order to preserve

her gorgeous coiffure.

Kazuko said times were better when there were

360 yen to the dollar: there were far more tourists and they

spent much more and tipped quite generously. The least favorable

exchange rate for outsiders was 80 yen to the dollar in 1995;

today the rate is 125, give or take. Another side effect of the

recession is the proliferation of "hostess bars" that

are replacing traditional geisha establishments. Though the tour

books indicate that a hostess is often a glorified prostitute,

Kazuko is quick to correct this misconception: it may take fifty

visits to the hostess bar at $750 a pop before you’ll have a

chance to get into the hostess’s pants. $37,500 is rather a

stiff fee for a prostitute, wouldn’t you agree?

Meandering back through the city streets, we

see yagi antennas and satellite dishes everywhere and conclude

that there is no cable TV in Japan. This, like the absence of

underground power lines, makes sense because of the extreme

earthquake-proneness of the Japanese islands. We pass a McDonalds

(there are reputed to be more than 2500 of them in Japan), but

this one has a subdued brown sign rather than the signal red of Tokyo’s (and

Washington’s!), as Kyoto imposes restrictions on the

garishness of signage out of respect for the softer appearance of

its traditional cityscape. We also pass a traffic accident that

is being attended to by police. The police will interview the

drivers and witnesses and decide which party is X% negligent and

which party is (100-X)% negligent, with the insurance carriers

partitioning the costs accordingly. Accidents are becoming more

prevalent as incidents of road rage become more commonplace.

Popular or not, we heard perhaps two horns being honked during

our weeklong stay in Tokyo and Kyoto. Kazuko’s insurance

premium of $700 per annum seems reasonable to an American (we pay

$2400 per year for a pair of Lexuses with only one speeding

ticket between the two of us in the last three years). Passing a

construction zone en route to the hotel district, we again note the

Japanese penchant for assigning names of juvenile simplicity to big

businesses: the predominant heavy construction firm in Japan, identified

by the signs flanking its work zones, is called simply Daitetsu,

"Big Iron"

—though I suppose one could come up with a

snappier English translation, say, "Ironmax" or "Mega

Metal."

—though I suppose one could come up with a

snappier English translation, say, "Ironmax" or "Mega

Metal."

We arrive at the Kyoto

Hotel in the heart of downtown (“market middle"

), where Kazuko advises us

to leave the bus if we want to grab a quick dinner and meet my wife's

Internet "pen pal," Manabu (more about him shortly). Crossing the

street, we see that the north-south "walk/don’t walk"

sign chirps rhythmically in a monotone, while the sign on the

cross street chirps rhythmically in two tones. This, we learn, is

for the assistance of the blind.

), where Kazuko advises us

to leave the bus if we want to grab a quick dinner and meet my wife's

Internet "pen pal," Manabu (more about him shortly). Crossing the

street, we see that the north-south "walk/don’t walk"

sign chirps rhythmically in a monotone, while the sign on the

cross street chirps rhythmically in two tones. This, we learn, is

for the assistance of the blind.

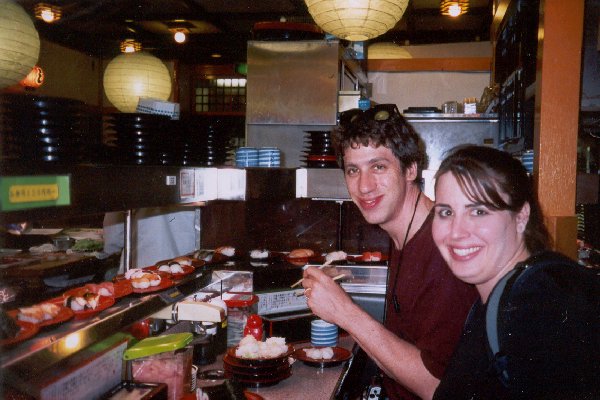

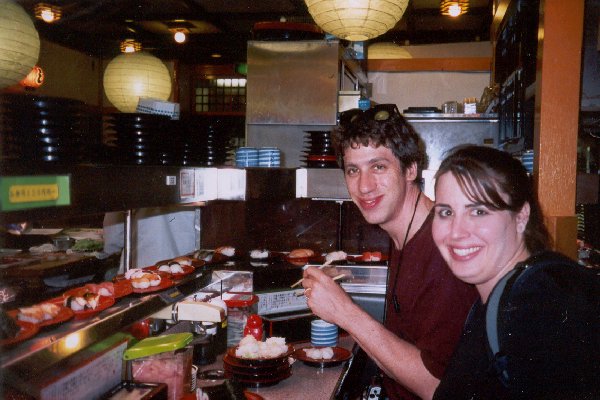

We ate at the Musashi kaitenzushi

("revolving sushi") restaurant where the patrons sit at a

counter and the food revolves on a conveyor belt of interlocking

metal plates like you see at the airport luggage carousel. (The

kai in kaiten  , which means "revolve" in this context, can also

express "repetition," "return," and even "inning" [as in baseball].)

, which means "revolve" in this context, can also

express "repetition," "return," and even "inning" [as in baseball].)

The older version of kaitenzushi used a

"sushi boat," but such bells and whistles have been

done away with, presumably in order to maximize the number of mouths

that can be simultaneously crammed into the joint and stuffed

with squid entrails. Cheryl ate five plates of food, while I ate

eight. I tried some more adventurous dishes, including the

octopus (which is tender and delicious, not like at home) and

some unidentifiable marine gastropods. Cheryl is, as usual, much

more conservative, clinging to the shrimp and salmon choices for

dear life among the dizzying assortment of headless and/or

tentacled slimy things. The other customers find it bizarre when

I scrape off the wasabi, but I find their lack of egos

rather more bizarre. Finally, the chef laughs when I pick up the

revolving Asahi beer can (it’s just an empty sample),

rushing me an ice-cold beer (either 12 ounces or 375 ml, I’m

not sure which) at the most unreasonable price of ¥350.

We walked over toward the subway

station—where teenage boys with earrings and torn jeans are

hanging out—to hunt for the statue of the bowing samurai,

where Manabu told us he would meet us at 7:30PM to give us a

personalized walking tour of the Gion district. In actuality, he

got there at 6:50PM, just a few minutes after we did.

Manabu—whose name means "study"  though he is

clearly no study animal—is 23 years old and recently

graduated from college with a degree in the social sciences. Not

surprisingly, his career options are limited with this

background, and he works part-time at a convenience store, but he

is taking some computer programming classes so that he can get a

good job. I’m not sure whether or not this is typical, but

he has no concept of the price of Japanese cars and has never in

his life visited either Tokyo (330 miles away) or Himeji (75 miles

away). Yet, he has been to the Netherlands. (I wonder what the

Dutch connection is—I met numerous Dutch and Belgian

tourists in Tokyo, and where of all countries does Manabu choose

to travel! I’m sure I’ll figure it out.) Manabu is very

friendly and shy and exhibits typical Japanese manners and

morals: when Cheryl presents him a gift of a Japanese-language

book about tourist attractions in Washington, DC, he almost

faints with appreciation, and when we stop later for a drink at a

convenience store, he is extremely reluctant to allow me to

purchase him so much as a one-dollar bottled water.

though he is

clearly no study animal—is 23 years old and recently

graduated from college with a degree in the social sciences. Not

surprisingly, his career options are limited with this

background, and he works part-time at a convenience store, but he

is taking some computer programming classes so that he can get a

good job. I’m not sure whether or not this is typical, but

he has no concept of the price of Japanese cars and has never in

his life visited either Tokyo (330 miles away) or Himeji (75 miles

away). Yet, he has been to the Netherlands. (I wonder what the

Dutch connection is—I met numerous Dutch and Belgian

tourists in Tokyo, and where of all countries does Manabu choose

to travel! I’m sure I’ll figure it out.) Manabu is very

friendly and shy and exhibits typical Japanese manners and

morals: when Cheryl presents him a gift of a Japanese-language

book about tourist attractions in Washington, DC, he almost

faints with appreciation, and when we stop later for a drink at a

convenience store, he is extremely reluctant to allow me to

purchase him so much as a one-dollar bottled water.

Kyoto, Manabu tells us,

lives by tourism and has suffered greatly since the depression.

Despite the image that foreigners may have, only a few

blocks’ worth of traditional wooden buildings remain in the

historic Ponto-cho and Gion districts.

By the way, the long curtains that hang over the entrance in lieu

of a door—like the brown ones, calligraphed in black, that grace

the following photo—are called noren in Japanese.

The rest either burned

down or were sold for the value of the land. I see lovely

restaurants with outdoor verandahs and beautiful views of the

canal (which used to be clean). The restaurants have melodramatic

names like Ishiriki (“One

Force"

) and "Chrysanthemum

Plum"

) and "Chrysanthemum

Plum"

. By the time we

emerge from the quaint side streets into the busier areas, we

have not seen any geisha. Manabu cautions us to watch out for

pickpockets. We are lucky to see a few interesting sights,

including a protest march (duly led by a policeman) and a

restaurant that charges $80 for a not-too-generous meal of shabu

shabu (a sliced beef "hot pot").

. By the time we

emerge from the quaint side streets into the busier areas, we

have not seen any geisha. Manabu cautions us to watch out for

pickpockets. We are lucky to see a few interesting sights,

including a protest march (duly led by a policeman) and a

restaurant that charges $80 for a not-too-generous meal of shabu

shabu (a sliced beef "hot pot").

Diversion on geisha: Arthur

Golden’s Memoirs of a Geisha (New York:

Vintage Books, 1997) is an award-winning historical novel

about life in the Ponto-cho and Gion sections of Kyoto.

Unfortunately, according to Manabu, many of the details

were concocted. Kyoko Aihara’s Geisha:

A Living Tradition (London: Carlton Books, 1999) is a

highly accurate, enthralling, and profusely illustrated

study of the geisha tradition.

More than once, Manabu expressed embarrassment

that his city is no longer as beautiful as it was in his youth. He seems

to feel a deep, individual shame at this, as if he’s personally

responsible for its decline. At least it’s not as hectic and

unfriendly as Tokyo,

he says. (We disagreed: we thought Tokyo was not so crowded, and rather

friendly—though my standard of comparison is New York. Now, standard

references indicate that Tokyo has nearly twice the population

density of New York [36,000 versus 20,000 persons per square mile], so

the only explanation I can muster is that Tokyo's relative cleanliness

makes it seem so much more spacious.) There are many drunkards on

the streets even though the beer vending machines shut down at

11:00PM. He says that, in general, Japan is going downhill,

probably due to overexposure to the dégagé lifestyle of the

West. Young Japanese no longer respect their nation’s

history and often cannot properly read or write the kanji. Both Manabu and I are in agreement that it

is only a matter of time before the archaic Japanese writing

system is completely supplanted by romaji.

We walk past a pachinko parlor. These are not

quite as plentiful as the travel guides would lead you to

believe. I ventured inside for a moment to try to determine what

it was all about, but the place was so loud, smoky, and offensive

with brilliant neon and flashing red lights that I found myself

nearly knocked backward—as if repelled by a force field. While

we’re all falling asleep on our feet and walking back to our initial

meeting point, we see a vendor’s truck set up on the

sidewalk to offer broiled octopus to go (the truck’s awning

depicts a cartoon octopus wearing a sushi chef’s hachimaki

headband), but Manabu advises us to avoid this food for

sanitation’s sake. He hails us a taxi, bids us a very

friendly farewell, and instructs the driver to take us back to

the Kintetsu station side of the New Miyako Hotel. Unfortunately,

the air conditioning is not on in the taxi and the night air is

quite muggy, but I don’t know enough Japanese to ask the

driver to turn it on. Oh, well, what can you do?

Back at the hotel, our room is indeed

comfortable; my fears that the classical muzak that was playing

in the corridors would be discernible from inside our room turned

out to be baseless. The thick buckwheat husk pillows are snuggly,

and the air conditioning is so ice-cold—even on the low

setting—that I must wake up several times to turn it now

off, now back on when the humidity climbs. Oh, well, who can

sleep anyway in this God-forsaken place where people are thirteen

hours out of synchrony with the real world? In the old cartoons,

one would dig a hole through the center of the earth and emerge

in Japan, where people were walking on their heads. They

weren’t that far off.

Mon 21

May Back to top

I had another decent (though not great)

night’s sleep, as I dreamed before awakening at 3:45AM.

Today we plan to go to Himeji Castle and, perhaps, the Osaka Aquarium. Cheryl

doesn’t know it yet, but our plans are subject to sudden

flux. Just between you and me, I think that Himeji will be a

rough hike, so I don’t really want to go to the Osaka

Aquarium afterwards—since it means yet another train ride and

yet another subway ride—and the 150-mile round trip to and from

Himeji is strenuous enough for a day of “leisure.” Maybe

we’ll go to Minachu on Nawate (the tour books told us about

it) to buy me some nifty zori or geta

thong sandals, or perhaps I’ll buy a new wristwatch at Isetan, since

mine is mysteriously losing about twenty minutes per day.

Our first stop is the Toji shrine flea market, which is held

monthly. As we will learn later from a (Caucasian) American girl

on our tour whose parents live in Kobe, the Japanese flock to

these “shrine sales.” After all, what more convenient

place to hock discount merchandise than in God’s own

precinct? Jesus would not approve. Walking through the quiet

streets at 6:00AM, past the ubiquitous neighborhood dental office

(labeled “tooth

science”

), beer vending machines, a fire station, and a

closed koban:

), beer vending machines, a fire station, and a

closed koban:

we enter the temple grounds, where merchants

are just now setting up prior to the 7:00AM-8:00AM

"official" opening. (Note the sign that advertises

kerosene—literally, “lamp

oil”

—for

sale; the preceding characters, “sun rock,” are presumably the

name of the firm.) I tried to pet one guy’s dog,

but, just like the lady at Ueno Park, the guy evidently perceived

me as an unwelcome intruder into his man-dog relationship. We

scored a gorgeous, century-old silk kimono, stunning black with

floral motifs near the bottom; an obi featuring a komainu

motif; and a second obi featuring a crane motif. All three

garments together cost under $120. I try to jew down one of the

merchants but succeed only in drawing giggles from the shrewd

grandmas as they pick through the piles of garments with their

clever, bony fingers. When I ask one vendor whether the price

includes tax ("tax

inside"

—for

sale; the preceding characters, “sun rock,” are presumably the

name of the firm.) I tried to pet one guy’s dog,

but, just like the lady at Ueno Park, the guy evidently perceived

me as an unwelcome intruder into his man-dog relationship. We

scored a gorgeous, century-old silk kimono, stunning black with

floral motifs near the bottom; an obi featuring a komainu

motif; and a second obi featuring a crane motif. All three

garments together cost under $120. I try to jew down one of the

merchants but succeed only in drawing giggles from the shrewd

grandmas as they pick through the piles of garments with their

clever, bony fingers. When I ask one vendor whether the price

includes tax ("tax

inside"

) by scratching out those kanji in my notebook

and flashing it before him, I draw a hearty laugh. Something

tells me that the government does not participate in the shrine

sale bounty. I stumble upon a statue that I think I recognize

from one of our guidebooks as Kukai, the monk who purportedly invented

the hiragana in the ninth century,

and the confirmatory dialogue with an elderly man ("Kukai?” “Kukai!") tells me that I’m correct.

) by scratching out those kanji in my notebook

and flashing it before him, I draw a hearty laugh. Something

tells me that the government does not participate in the shrine

sale bounty. I stumble upon a statue that I think I recognize

from one of our guidebooks as Kukai, the monk who purportedly invented

the hiragana in the ninth century,

and the confirmatory dialogue with an elderly man ("Kukai?” “Kukai!") tells me that I’m correct.

Trying to find the exit, we have to rely upon

Cheryl’s compass, but it isn’t helping with all the

metal booths everywhere. Finally escaping, we take a taxi back to

the hotel in preparation for our haul by shinkansen to Himeji.

We need breakfast, and not much is open, but

Mr. Donut is rocking and rolling—quite literally. While

lined up to choose our donuts from the wide

selection—featuring, oddly enough, the world-famous egg

salad donut—the audio system is playing the Beach Boys,

"The Wanderer," Neil Sedaka’s "Next Door to

an Angel," and "My Boy Friend’s Back." Is this

what they think of modern American culture? Whatever; we pay for

our treats, receive bows and scrapes, and sit down to enjoy our

"American-style" meal.

Looking at a poster in Mr. Donut, I can’t

figure out what purpose the character for "sun" serves.

I know that it is used to mean "day" as well as

"sun." Aha! It means "Sunday" as well. The

Japanese are using the Chinese designations for days of the week,

putting the single character (without the equivalent of our

–day suffix) in parentheses just after the numeric day:

Sunday = sun

Monday = moon

Tuesday = fire

Wednesday = water

Thursday = wood

Friday = metal

Saturday = earth

I know that English has words overloaded with

multiple meanings, but they seem to make sense. You cannot

convince me—no matter how hard you try—that it makes

any sort of sense for "mother" to mean

"each" when it appears on a Kyoto parking sign, as in, “each 30 minutes, 200 yen"

.

.

Entering the shinkansen waiting area, we notice

that a pair of uniformed attendants is giving every customer a

big bow and an accompanying "Arigato gozaimasu!" but few people reciprocate with a bow. I must

say that this regimented politeness becomes annoying after a

while, and I have no doubt that it comes across as so automatic,

so superficial, that even the older Japanese are occasionally

disgusted by it. I see a fat guy on the Shin-Osaka platform—possibly the

first fat person I’ve seen since our sojourn in Japan began

last week (maybe he’s been eating too many egg salad

donuts)—but this will change now that they have Western

food, including pizza that, according to the shrine sale maven,

is customarily offered with mayonnaise.

There are very few

passengers on this shinkansen, and no conductor appears to check

our tickets. This is the Sanyo line, not the Tokaido line, and I

believe it’s operated by a different Japan National Railways

subsidiary. We notice another difference: perhaps the sensor that

flushes the toilet has malfunctioned, since the commode is

stuffed with paper. I’m shocked to see such a thing in a

public place in Japan.

The countryside is much

quieter here than it was to the east. We pass the new Pearl

Bridge that crosses from Honshu to Awaji-shima on the way to

Shikoku. I think this is the one that charges a $27 toll, a

multi-billion-dollar engineering marvel that spans several miles

and was the subject of a recent documentary on the Discovery

Channel.

It is drizzling when we

arrive in Himeji after a fifty-minute ride, but it quickly clears

up. Though the town is relatively small, there is a bustling

downtown with high-rises just outside the train station. There

are tons of bicycles on the main street, mostly ridden by ancient

people. We pass much statuary on the main street plus the first

pet store we’ve seen in Japan. The puppies inside are

barking plaintively in Japanese, “Please don’t sell me

to a Vietnamese restaurant!” The city abruptly ends as the

storied fortress of Himeji-jo with its extensive, moated grounds

looms overhead.

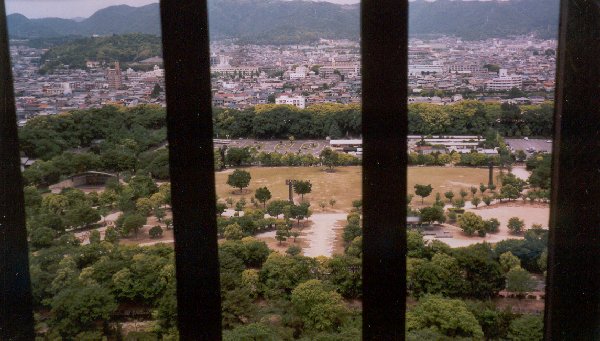

The castle, built in

1600, is imposing, awe-inspiring, magnificent. I can confidently

declare now (and affirm it more strongly after our tour) that

nothing in North America even comes close—and I’ve seen

them all: Toronto’s Casa Loma,

St. Augustine’s Castillo San Marcos, Québec’s Citadel,

and Miami’s Vizcaya. Here's a bit more detail of the masterful

wooden joinery and roofing tile structure, which conceals seven

levels in what looks from the outside like five:

They illuminate the place with huge floodlights

at night, which must look very dramatic, and I’m told that

the titanic electric bill is actually an identifiable (i.e.,

non-trivial) component of the average Japanese citizen’s

income tax.

We pay ¥1200 for admission for two and ask for

an English-speaking guide (no signs announce their availability,

so we’re fortunate that Cheryl boned up on the place).

Yoshimi, a short, pudgy, cheerful lady, shows up almost

instantly, and it’s apparent that we will receive a most

private tour. (In retrospect, I wonder how Yoshimi could be so

squat, since the amount of exercise she gets daily by marching

all over this place is astonishing.) Yoshimi tells us that the

tour should take ninety minutes, but we know that, with my

questioning mind, she’s in for about twice that long. Just

inside the entrance gate is a stunning collection of bonsai. For

the next three hours, we tramp up and down hallways, up seven

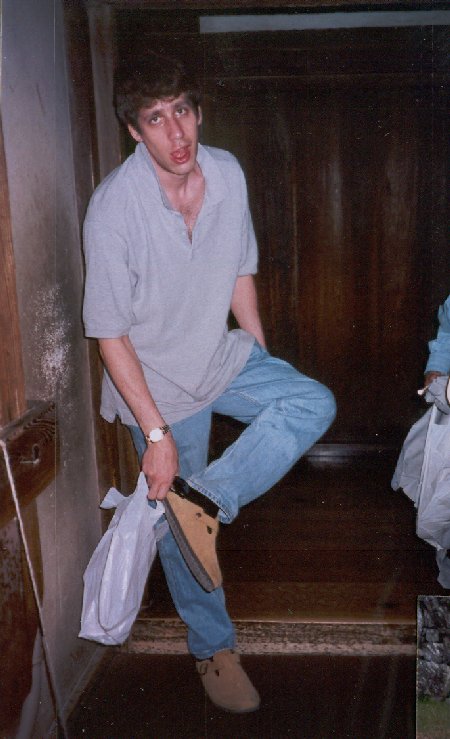

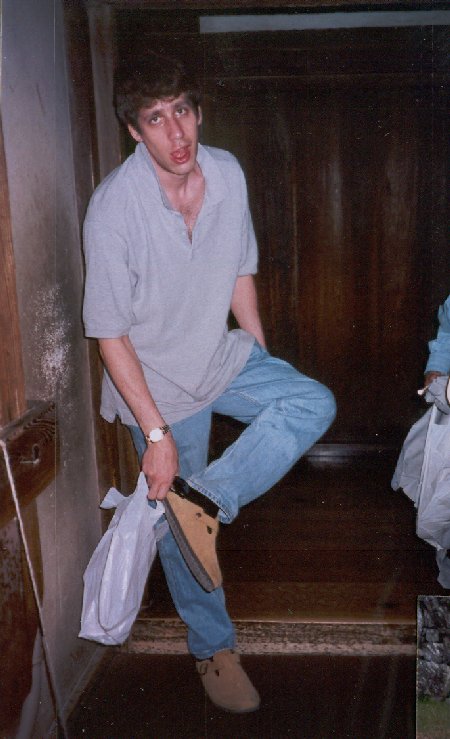

levels of the steepest stairs, constantly taking off shoes

(relegating them to plastic bags that we carry with us, rather

than leaving them on shelves) and putting on shoes so as not to

damage fine wooden floors. (I'm glad I wore clogs, since they slip on and

off my feet instantaneously without having to fuss with laces. The

evident Japanese fixation with constantly doffing and donning shoes

makes it crystal-clear why the thong sandal and its derivatives became

the mainstay of the Japanese footwear armory.)

The fortress is spellbinding not only for its

architecture (Japanese cypress above with skillful

tenon-and-mortise joinery, stone below) and the anecdotes that it

conjures up, but also for the fact that it is a living museum of

constantly changing art, artifact, and textile exhibits.

The castle is ingeniously designed with

dead-ends, hidden levels, slippery walls, and deadfalls, and it

is set within gorgeous wooded grounds that overflow with tsutsuji

(azalea) trees. Although living accommodations are crude in the

donjon—since it was used for defense—the women’s

quarters in the west bailey are quite pleasant by medieval

Japanese standards. It is interesting to learn, upon seeing gun

ports in the castle wall, that samurai did not depend exclusively

on swords: indeed, the various daimyo had

purchased some 200,000 muskets from the Portuguese by the early

1600s. Himeji-jo was

built during a period of history in which building materials were

hard to come by, so stone came from wherever. I mean literally wherever: one can descry both tombstones and kofun

(cists) in the wall, rudely appropriated from cemeteries with

their owners’ inscriptions still in place. There is also,

clearly marked, some desperately poor old lady’s millstone.

When she heard that the daimyo needed

stones to build his fortress, she donated the cherished

millstone—even though it left her without the wherewithal to

feed herself. She received no monetary reward, but the daimyo

was very grateful. (They probably recorded the deed on her

tombstone, which was subsequently recycled into the castle wall!)

Diversion on Japanese language:

I have been having more fun spotting kanji co-significs

on signs. In particular, nail is "metal post"

and pillar

is "master

tree"

and pillar

is "master

tree"

.

"Guest" is "roof legs mouth"

.

"Guest" is "roof legs mouth"  , hotel is

"roof hundred

men"

, hotel is

"roof hundred

men"  , and

"kiln" is "enclose pottery"

, and

"kiln" is "enclose pottery"  . Gleaned from

the stag aggression warning at Nara: "sex" is

"heart birth"

. Gleaned from

the stag aggression warning at Nara: "sex" is

"heart birth"  . (The left-hand radical in this character

is a very streamlined version of the stand-alone character for

"heart"

. (The left-hand radical in this character

is a very streamlined version of the stand-alone character for

"heart"  , which—to me—establishes a striking minimalistic likeness of

the human heart in only four brush strokes.) Shifting

gears, "ankle" is given by "foot fruit"

, which—to me—establishes a striking minimalistic likeness of

the human heart in only four brush strokes.) Shifting

gears, "ankle" is given by "foot fruit"

(viz.,

the round protuberance of the human foot). As was remarked

earlier, however, one cannot make sense of the overwhelming

majority of kanji in this fashion: no amount of creative

analysis can explain, e.g., why a "nun" is a

"corpse spoon"

(viz.,

the round protuberance of the human foot). As was remarked

earlier, however, one cannot make sense of the overwhelming

majority of kanji in this fashion: no amount of creative

analysis can explain, e.g., why a "nun" is a

"corpse spoon"  —nor will mastering

that fact help you remember that "water nun"

—nor will mastering

that fact help you remember that "water nun"

means "mud," even if the presence of the water

radical reveals that the word bears some relationship

to water.

Next linguistic diversion or

previous

means "mud," even if the presence of the water

radical reveals that the word bears some relationship

to water.

Next linguistic diversion or

previous

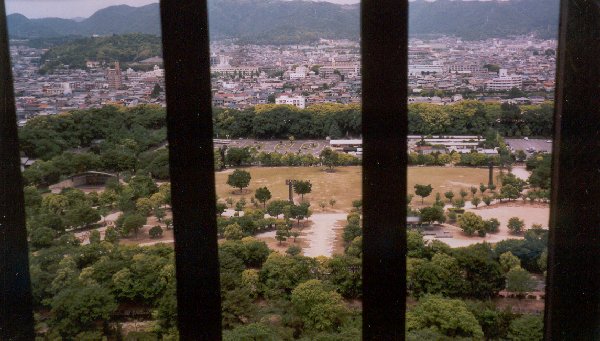

We encounter more racism here. Some people on

the castle steps mock us (one can detect mockery in any

language), and the guide quickly puts them in their place. Later,

when I offer to help an ancient lady negotiate the steep steps

(and I do mean steep—perhaps 65°) to enjoy the panoramic

top-floor view of the surrounding areas of Hyogo prefecture ("Soldier Garage"

,

viz., "Barracks"—perhaps an odd name for a major

political division, but clearly no more odd than "Snowy" [=

Nevada]):

,

viz., "Barracks"—perhaps an odd name for a major

political division, but clearly no more odd than "Snowy" [=

Nevada]):

she patently refuses. She would evidently rather

tumble to her death than have a Caucasian assist her. Now, in Tokyo, there was some limited

racism, but I was never mocked. It would appear that Kyoto and

environs is rather more ethnocentric than Tokyo.

Diversion on Japanese language: I

detected another, most fascinating, manifestation of Kyotoan

atavism, which is a bedfellow of ethnocentrism. Japanese

was long written in vertical lines of text, the reader scanning

subsequent lines from right to left, but has more recently

appeared as horizontal lines of text, the reader scanning subsequent

lines from top to bottom—the way most European

languages are read. (These styles are referred to as washiki [Japanese style, literally,

"harmony style"] and yoshiki [Western style, literally, "Atlantic

style," both of which were introduced in kanji

earlier].) Though every sign in Tokyo was writtem yoshiki,

many signs in Kyoto were written washiki.

Next linguistic diversion or

previous

There is a stone well on the castle grounds

that has its very own Japanese ghost story. A samurai was once

plotting to kill the daimyo who owned

the castle. A maiden discovered the plot and informed the lord.

The samurai, thinking quickly, stole a valuable dish and

frivolously accused the maiden of stealing it. When she was

absolved, the samurai vowed revenge, tortured her to death, and

threw her body into the well. Thereafter, her ghost rose from the

depths every night to count the dishes—until a small Shinto

shrine was built to quiet her restless spirit. My evil mind longs

for details on how the samurai tortured the maiden, but I quickly

conclude that the Portuguese Jesuit missionaries surely

introduced the entire arsenal of the Spanish Inquisition into

Japan, so we needn’t worry about insufficient technology

hampering the samurai’s sadistic creativity.

On the way out, I mention the moss garden at

Saiho-ji to Yoshimi

and ask why I cannot find it in any tour books. I still remember

the caption of National Geographic’s photo of it in Majestic Island Worlds (R. M. Crum, ed.;

1987), which was enough to make one drool: "Twisted maples,

a secluded pond, and more than 120 kinds of mosses adorn Kyoto’s Saiho-ji, or moss

temple … Ornamental koi, or

carp, flash in an azalea-edged pond." Yoshimi tells us that

not even a Japanese person is allowed there unless he applies for

permission and is accompanied by a distinguished foreign visitor,

and it is strictly off-limits to tour groups—that’s why

it still exhibits such paralyzing beauty. There isn’t a

thing that Yoshimi forgets to tell us—other than the most

obvious thing of all (that we knew anyway from the guidebook):

Himeji-jo is

popularly referred to as the “white egret castle”

because of its color and the graceful, winged profile of its

eaves. It may—or may not—be coincidental that the kanji for "egret" incorporates the

character for "path" that is also part of the kanji

for Himeji ("princess

path"

because of its color and the graceful, winged profile of its

eaves. It may—or may not—be coincidental that the kanji for "egret" incorporates the

character for "path" that is also part of the kanji

for Himeji ("princess

path"

).

(The fact that a "popular" name includes the word

"egret" reveals how educated the Japanese are: what

site in the U.S. would be referred to in slang by a word that

three-fourths of the adults probably don’t know?)

Egret-related omissions aside, we were so blown away by

Yoshimi’s expertise and enthusiasm that we offered her a

¥2000 tip, but she declined, saying that she’s not permitted

to accept it or some other pathetic excuse.

).

(The fact that a "popular" name includes the word

"egret" reveals how educated the Japanese are: what

site in the U.S. would be referred to in slang by a word that

three-fourths of the adults probably don’t know?)

Egret-related omissions aside, we were so blown away by

Yoshimi’s expertise and enthusiasm that we offered her a

¥2000 tip, but she declined, saying that she’s not permitted

to accept it or some other pathetic excuse.

We schlep back to the train station, the better

part of a mile. The gentleman next to me waiting for the

shinkansen back to Kyoto

gets his e-mail on his cell phone in kanji,

which I find amazing. On the ride back, we see the usual farm

next to factory next to high-rise next to cemetery next to

convenience store in haphazard manner. Welcome to Japan. Our

tickets once again won’t let us out of the station, so we

must extricate our JR passes to show to the station attendant. We

arrive back at Kintetsu station dead-tired at 3:00PM, just in

time to see another massive school group—including two boys

playing shogi readying for a train trip to God knows where. Shogi

is Japanese chess, played on a 9x9 board, with all the pieces the

same shape (as well as the same color!) but labeled with kanji

indications of their ranks and "color." (Try to imagine

playing chess with checkers that are labeled K, Q, R, and

so on rather than being artfully shaped like horses and castles

and such that enable one to visually grasp the

position—not a pleasant prospect!)

Now, Cheryl still wants to find her kokeshi

doll, so we hunt for the famous "The Cube" mall. We

pass a Roy Liechtenstein poster, and I find it humorous that his

name (Roi Likutensutainu) is spelled out in katakana. It

turns out that "The Cube" is merely the basement level

of this station complex, and the eight or so shops vend the same

junky gifts as any other place—fans, scrolls, dolls, lacquer

boxes, shoddy kimonos, etc. Hunting through Isetan for a kokeshi,

we find an ostensible Chinese restaurant on the top floor and

decide to have a leisurely early dinner. The place looks

lovely—although the décor is a bit Spartan and those guys

are smoking (terrific, they’re getting ready to

leave)—and the menu overflows with mouth-watering

photographs of the dishes. I try to order a plum wine, since I

know the kanji for both "plum" and

"wine," but the Japanese are evidently so

memorization-oriented that, if a Westerner makes the slightest

error in composing or combining characters, they just stare at

the glyphs, clueless. I therefore decide to forgo the wine and

instead focus on entrees. The dishes are fresh and delicious,

of absolutely superb quality—mine is sautéed abalone with mushrooms;

Cheryl’s is a beef and scallops medley with

broccoli—but the portions are barely adequate for an

elementary school luncheon, so I can’t fathom why the bill

came to almost $50.

Diversion on Japanese language:

Hunting for more co-significs, I find that oak is "elephant tree"

(viz., the tree whose trunk is

gnarled like an elephant) and that princess is "official woman"

(viz., the tree whose trunk is

gnarled like an elephant) and that princess is "official woman"

. We learned earlier that many place names

and personal names are simple nature-oriented compounds,

and the same is evidently true of major Japanese

corporations: Honda means simply "main paddy"

. We learned earlier that many place names

and personal names are simple nature-oriented compounds,

and the same is evidently true of major Japanese

corporations: Honda means simply "main paddy"

, while

Mitsubishi means "three water chestnuts"

, while

Mitsubishi means "three water chestnuts"

.

Next linguistic diversion or

previous

.

Next linguistic diversion or

previous

We are back at the hotel, and I’m ready to

collapse. The prices here are so pathetic: a piece of cheesecake

peculiarly labeled "rare cheese" costs twelve dollars,

while a strawberry tart the size of my big toe sets you back more

than a sawbuck.

No more adventures tonight, dear. I’m so

utterly exhausted that I can barely stand on my feet. At 5:30PM

and 6:00PM they play Japanese cartoons. The animation is of

excellent quality, but I’m unable to follow the plot, which

involves what looks like a Revolutionary War hero rowing his

sweetheart in a boat while three animals—including a talking

camel—hike along the mountain road that follows the river

just overhead. I head downstairs for a light supper, which

consists of a few sweet treats from Mr. Donut plus a Diet Coke

(for Cheryl) and an apple-pear-carrot juice (for me) procured

from—guess what—a vending machine down the block, then

it’s "lights out" at 7:30PM.

Onward

—we used to

call him Gigantor when he played on American TV in the

1960s), but I strike out. Since we know that the shinkansen

platforms won’t open until 5:30AM, we content ourselves with

our old friend Shihab Rattansi on CNN news (at least it’s in

English; the other choices are French news and German news). I

also watch a Japanese chemistry ("change

study"

—we used to

call him Gigantor when he played on American TV in the

1960s), but I strike out. Since we know that the shinkansen

platforms won’t open until 5:30AM, we content ourselves with

our old friend Shihab Rattansi on CNN news (at least it’s in

English; the other choices are French news and German news). I

also watch a Japanese chemistry ("change

study"

—peculiarly

enough, not "change science"

—peculiarly

enough, not "change science"

—but akin to

the "ancient study"

—but akin to

the "ancient study"

that means

"archaeology") lesson on channel 4, an evident game

show on another station, and photos of old Japanese rural

life—set to hokey music—on yet another.

that means

"archaeology") lesson on channel 4, an evident game

show on another station, and photos of old Japanese rural

life—set to hokey music—on yet another.

), "center"

), "center"  , and "window" (literally, "side"

, and "window" (literally, "side"  —the character makes no reference to

glass). There is no carpet. The seats recline, and entire racks of

seats can be rotated to form conversational groups for four or

six persons. The luggage racks overhead ingeniously slope

downward toward the walls so that luggage won’t spill when

the train lists. Cheryl was careful to choose seats that are in

the last row of the car (behind which there is a generous area

for our large suite of luggage) and on the Mount Fuji side

(hoping for a view thereof). There are entrances at both the

front and rear of each car, and markings on the platform indicate

precisely where each set of doors will open. Every other

car has washrooms (both Japanese and Western) and a urinal with a

peculiar see-through window. I wonder about the first-class

"green car" but don’t get to see it yet.

—the character makes no reference to

glass). There is no carpet. The seats recline, and entire racks of

seats can be rotated to form conversational groups for four or

six persons. The luggage racks overhead ingeniously slope

downward toward the walls so that luggage won’t spill when

the train lists. Cheryl was careful to choose seats that are in

the last row of the car (behind which there is a generous area

for our large suite of luggage) and on the Mount Fuji side

(hoping for a view thereof). There are entrances at both the

front and rear of each car, and markings on the platform indicate

precisely where each set of doors will open. Every other

car has washrooms (both Japanese and Western) and a urinal with a

peculiar see-through window. I wonder about the first-class

"green car" but don’t get to see it yet.

? The answer

is that square + face means "direction" or

"toward." The washrooms are marked

"harmonious style" (literally, "rice-in-mouth style"

? The answer

is that square + face means "direction" or

"toward." The washrooms are marked

"harmonious style" (literally, "rice-in-mouth style"

)—meaning simply "Japanese

style"—or "Western style" (literally,

"Atlantic

style"

)—meaning simply "Japanese

style"—or "Western style" (literally,

"Atlantic

style"

. Is that

it? I think so. No, wait a minute: I think it’s that

mountain over there. All of this speculation ends abruptly when

we happen upon Fuji. There can be no mistake. This magnificent

snow-capped volcano fills the entire sky. Though the vistas have

largely been spoiled by power lines, this isn’t the case

here (probably because power lines don’t reach the

12,388-foot level). The gentleman in front of us tells us that we

are quite lucky to obtain such a fine view of Fuji, since

it’s usually shrouded in mists and fog. (Of course, the

pictures in books show empty fields near Fuji, not suburbs. They

must have been taken from the rural north of Honshu, not from the Tokaido [“Pacific

Way,” literally, “Eastern

Ocean Way"

. Is that