TRAINS, TEMPLES, AND HORDES—GOZAIMASU! (continued)

Bruce David Wilner

July 2001

Sun |

Mon |

Tue |

Wed |

Thu |

Fri |

Sat |

15 |

16 |

17 |

18 |

19 |

||

20 |

21 |

22 |

23 |

|

||

Today is our free day in Tokyo. Up early, I discover that this country also has its assholes: trying to convert ¥95 in loose change to a ¥100 coin that the vending machines will accept, the desk clerk staunchly refuses—despite my puppy dog eyes—unless I cough up the missing ¥5 (4 cents). You would never see that in America. Just for kicks, we take the hour-long Yamanote ride all around Tokyo to watch the sleepy Japanese commute to work. (Actually, the Yamanote only loops around the city center; it seems that many foreign cities’ subway networks include this type of central loop line, plus numerous diametrical lines that intersect the loop twice.) I’m getting used to having to continually undo my shirt and unzip my passport belt to extricate the JR passes to show to the station attendants. Some actually open the passes and check the date, while others just wave us through. (We always have to show our passes on the way out of the station, since the automatic turnstile scanner always rejects our tickets—which are evidently configured in "foreigner mode.") Many businessmen on the train have earplugs or Walkmen, and everyone seems to have established a quiet psychological bubble around himself. I chat briefly with one gentleman on the subway, largely by scratching out kanji at a fifth-grade level in my notebook, but most of the people do not condescend to try to communicate. (This stands in such stark contrast to America, where people often go out of their way to assist foreigners.)

I’ve finally figured out why they play these stupid ditties at the train station. It is to wake people so that they don’t miss their stops. One frequently heard melody (treble clef, key of A major, 3/2 time signature) is:

while another (treble clef, key of C major, 4/2 time signature) is this:

(Please pardon the peculiar time signatures and notational conventions: Microsoft PowerPoint isn't the most convenient vehicle for conveying musical notation—plus, working from rough notes and memory, I had to steer as best I could around the absence of quarter and eighth rests from my clip art collection.)

Some people are "feet people," my wife says. I’m one of them, so I carefully inspect the subway riders’ shoes (they say a lot about a person, I think) and then northward if I’m interested. I see two people with sand suede Clarks’ Wallabees—I’ve owned one or more pair continuously since 1979—but they’re the cheap new kind made in China for $110, not the classic, top-quality $170 Irish handmades that every upper-middle-class Jewish boy wanted to own when I was in high school (they cost only $60 then, but that was a fortune for the times—more than twice the price of the fanciest sneakers on the market). I see black shoes worn with white socks on the typical businessman, which makes me laugh. I see peculiar-looking orange and yellow Nike sneakers, Fila caps, and the dorkiest T-shirts I’ve ever witnessed (including one that says "Labrador Retriever" but has a silhouette of what looks more like a cocker spaniel, and a Mickey Mouse T-shirt worn by a middle-aged adult whom, I suspect, has no idea what a Mickey Mouse is).

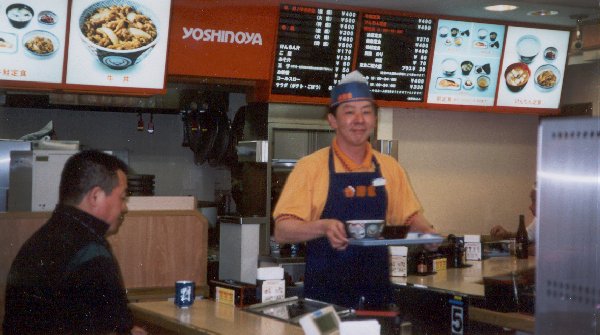

Back from our loop around city by 6:00AM, I stop in at the men’s room in the train station and find that it’s reasonably clean. One surprise is metal bars around a reduced-height urinal, evidently to accommodate the infrequently seen handicapped. It is difficult to find a Japanese-style toilet here, and the guidebooks that warned us to bring our own toilet paper were basically flat-out wrong. (My wife’s perspective is that I’m totally wrong here, since the women’s restrooms were nearly all Japanese-style and she found them basically disgusting.) Out on the streets, the city is wide awake at 6:45AM. We grab a curbside "breakfast" of beef teriyaki plus broiled salmon fillet plus pickles plus rice for two adults for only ¥900 at Yoshinoya.

(Behold how the short-order cook beams with pride for the camera as he presents his fast-food handiwork.) Then it’s back past the ukiyo-e sidewalk decorations and prostitutes’ calling cards to take our old friend, the Yamanote line, back to Ueno Park just northeast of the city center.

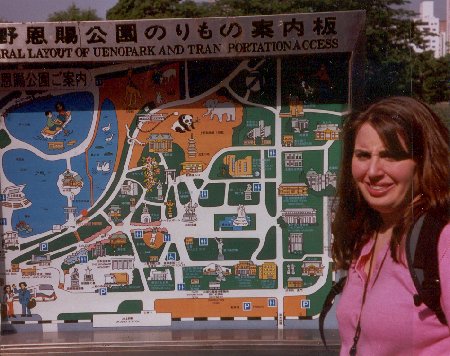

My first impression of Ueno Park is that it tries hard to be like Golden Gate Park—except it isn’t one-tenth as beautiful or as large. There are plazas, fountains, woods, a zoo, several museums, some shrines, tons of vending machines—and lots of homeless (either sleeping on park benches or living in not-too-subtle blue plastic tents scattered among the groves), but the park somehow misses the mark.

Some people are walking (not many run or jog here) and an impromptu Buddhist meditation group of eight souls is sitting lotus-style on the ground listening to taped mantras. I try to befriend some lady’s long-haired dachshund, but he almost bites my head off. In general, the dogs here—nearly all of which are the wallet-sized variety—are not friendly, and people do not pet, make kissy-kissy at, or admire one another’s dogs here as they do at home. We see more stray cats—again, very timid—and an ancient gentleman feeding the pigeons (oops, doves) pieces of bread.

Of course, thanks to our peculiar schedules, we were ready to

rock at the Tokyo National [Art]

Museum (“Eastern Capital Nation Stand

Beautiful Crafts Building"

) at 7:50AM

though it doesn’t open until 9:30AM, so we wander around and

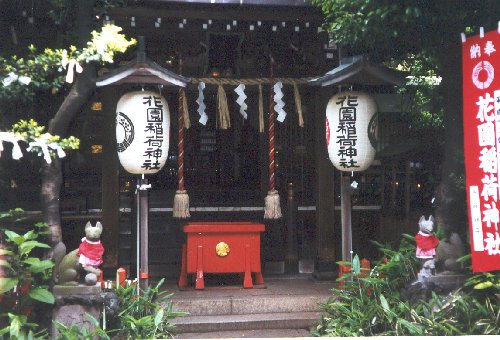

back, finding a lovely shrine dedicated to the fox god Inari:

) at 7:50AM

though it doesn’t open until 9:30AM, so we wander around and

back, finding a lovely shrine dedicated to the fox god Inari:

swan-shaped paddleboats for rent on a lovely, lotus-filled pond (note freaky-looking apartment building in left background):

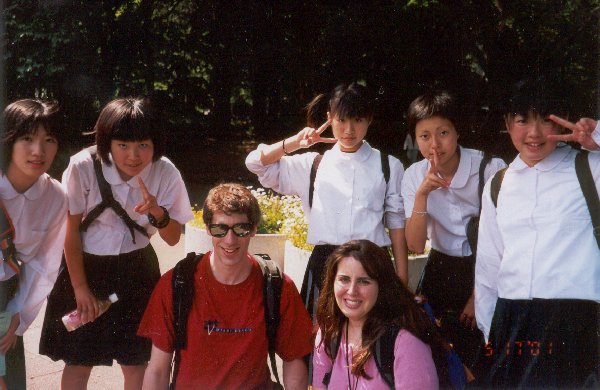

and old people hanging out in the morning sun. Outside the museum, a group of schoolboys (dark blue uniform jacket, dark blue uniform pants, child’s choice of sneakers) was being marshaled by the English teacher, who warmly welcomed us to Tokyo, and an unrelated set of schoolgirls (white and dark blue “sailor suit” style uniform blouse, plaid uniform skirt, child’s choice of sneakers) rushed over to test out their English and ask us to write our names in their books. The girls make 1970-style peace signs with their fingers while posing with us for a group photo, which strikes us as quaint.

A third set of schoolboys is sitting on the ground preparing for their group photos. (Although the school year runs from April to March, senior trips always take place in May.)

Back in the museum, the exhibits were of the first quality, but they were spaced far apart, which is ironic for such a small country. We saw a small but fine collection of ukiyo-e woodblock prints by the most renowned masters (Hokusai, Hiroshige, Utamaro); numerous folding, painted shoji screens, including nipuku-tsui (diptychs) and sanpuku-tsui (triptychs); complete suits of samurai armor with helmets supposedly depicting rabbits’ ears (the rabbit is a symbol of virility, they tell me—which seems logical, at least for a boy rabbit):

breathtaking antique kimonos sewn with real silver and gold (this one depicts mice attacking a carrot):

and tunics woven from shredded tree bark (!), the standard garb of the Ainu, the "native" Caucasian inhabitants of Hokkaido:

The museum doesn't allow flash photography, so I only managed to take the preceding photos (yes, with the flash) by repeatedly apologizing to the guards, “whoops, I’m not sure why that flash went off”—accompanied by fiddling with the camera’s buttons and a perplexed facial expression—until the excuse began to wear thin. Thus, when I got to the rooms containing the plentiful collection of ukiyo-e prints, I dared not snap any more pictures. I'm not sure of the magnitude of this loss: I’ve seen my share of ukiyo-e in New York, Washington—even Cleveland—and I can’t even imagine the wonders of Honolulu’s Michener museum, which houses nearly the entire collections of Hokusai’s Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji and Hiroshige’s Fifty-Three Stations of the Tokaido Road.

(The carrot kimono reminded me of a Japanese ukiyo-e I saw in Cleveland in 1985 or so that was attended by the following legend:

A certain man swore by the benefits of daikon radish. Every morning, he cooked and ate two of them for breakfast. Once, the man’s enemies fell upon him and attacked his homestead. Suddenly, two samurai appeared, who fought with such intensity that the attackers were repelled. "We are the spirits of the daikon," they told the man, "who came to your aid because you believed in us."

I’m still scratching my head over it sixteen years later. Perhaps it’s allied to the reliance upon Popeye« cartoons to convince 1930s American youngsters to eat their spinach.)

After the museum, we’re exhausted from jet lag, so we sit

on a park bench and hit the vending machines. Cheryl gets a Diet

Pepsi, which, she claims, does not taste like the Diet Pepsi at

home, while I buy something called "Refining the

Vegetable" that apparently incorporates apple, pear, and

carrot juice. The combination looked strange, but I bought it

anyway because at least it was 62% fruit

juice

and 38% vegetable juice

and 38% vegetable juice

, not the 10% or 33%

mix that one so often sees. Fortunately, the fruit content is

always clearly—nay, prominently—indicated on the front

of every can, apparently by law. (I discover the value of this

after I return home and purchase a "black cherry" soda

from a vending machine. When it turns out to taste like shit, I

scrutinize the can and eventually find evidence that it contains

0% fruit juice.) Oh, well: at least these kanji are

straightforward—unlike the ones on the duckling-graced sign

seen at every Tokyo construction site:

, not the 10% or 33%

mix that one so often sees. Fortunately, the fruit content is

always clearly—nay, prominently—indicated on the front

of every can, apparently by law. (I discover the value of this

after I return home and purchase a "black cherry" soda

from a vending machine. When it turns out to taste like shit, I

scrutinize the can and eventually find evidence that it contains

0% fruit juice.) Oh, well: at least these kanji are

straightforward—unlike the ones on the duckling-graced sign

seen at every Tokyo construction site:

that proclaim "tranquil complete number one," viz., "safety first!"

We next hop on the Yamanote back to the other side of town

(Shibuya) so that Cheryl can search for her 100-yen store. The

crowds bursting out of the Shibuya train station at lunchtime are

overwhelming. Even in New York, I’ve never seen such hordes

of people. Since we don’t know where to look for the store,

we ask at the police at the conveniently located koban and immediately receive

a detailed neighborhood map and crisp English directions. We

still manage to get lost several times, so we stumble into a

small restaurant on an unnamed street and have delicious plates

of unagi. I am dismayed by the presence in the miso

soup of carp bones united by ribbons of flesh—maybe

they’re trying to choke the gawky foreigners to

death—but we later learn that carp bones are often used in

high-quality soup stocks. While dining, Japanese racism (maybe

just xenophobia) again manifests ever so subtly: a duo of

Japanese ladies who enter the restaurant and are directed to the

table next to us clearly express their preference for that table

way over there. Exiting the restaurant, we see a variety of

interesting scenes. A Red Cross blood drive is discernible by the

appearance of the kanji character for blood  on that large sign between the

megaphone-toting barkers. Two uniformed men are loading an

armored car (an Isuzu Elf, which is about as wide as my left

foot). Another team of barkers, looking awfully silly in their

more-or-less accurate Uncle Sam getups, advertises a (legal?)

American-style casino joint. Finally—and most

surprisingly—we see two dangerous-looking black American

homeboys hanging out. They are discernible at quite a distance by

the steady stream of "fuck" and "mother

fucker" issuing from their mouths. Again, we trip on the

sidewalk umpteen times and nearly dash our brains out, since,

although the concrete is not in the best condition, "Watch

your step" signs are nowhere to be found.

on that large sign between the

megaphone-toting barkers. Two uniformed men are loading an

armored car (an Isuzu Elf, which is about as wide as my left

foot). Another team of barkers, looking awfully silly in their

more-or-less accurate Uncle Sam getups, advertises a (legal?)

American-style casino joint. Finally—and most

surprisingly—we see two dangerous-looking black American

homeboys hanging out. They are discernible at quite a distance by

the steady stream of "fuck" and "mother

fucker" issuing from their mouths. Again, we trip on the

sidewalk umpteen times and nearly dash our brains out, since,

although the concrete is not in the best condition, "Watch

your step" signs are nowhere to be found.

I slip into a manga shop to hunt for a sexy comic. We have heard that these are big business in Japan. It takes no time flat for me to find a book-sized comic that features the most explicit scenes of white girls having physical fun with macho white men, stern Japanese masters, even an American Indian chief. The comic is skillfully slipped into a brown paper cover and into my knapsack. I’m really not much of a fan of explicit magazines, but I had to buy one here as part of my sociological research.

We finally locate the 100-yen store. It is five stories high:

and is barely distinguishable from an American dollar store

(except that these goods cost only ¥100 [$0.80]—which

would lead me to expect inferior quality, except that Tokyo is closer to China). As is typical of

downtown Tokyo establishments, each “floor” has no more

surface area than my earlobe and is connected to its neighbors by

flights of breakneck stairs. Cheryl fills a basket with cheap

gifts while I bitch heartily about how she dragged me all over

Tokyo for this dreck. Here is what she picked up for $20: 2 black

lacquer bowls with tacky gold design; 1 inscrutable

Japanese-looking object with silica gel packs labeled “do

not eat”; 1 bamboo steamer tray labeled “made in

China”; 2 inflatable paper lanterns—one red, one white;

2 packages richly patterned origami paper; 2

God-knows-what with several varieties of colored paper and

metallic ribbon; 1 brown noren curtain (like the ones that hang over the

thresholds of restaurants) with white cherry blossom pattern; 3

wooden parasols (again, “made in China”)—two blue

with floral motif, one white with red kanji reading

"Kyoto”; 1 small red

square cardboard box with gold vine-and-leaf pattern; 1 package

of four chopsticks (two red, two blue); 2 postcards (one of

famous Hokusai print, one of famous Utamaro print); 2 pairs

miniature geta (traditional wooden thong sandal)

ornament—one red, one blue; and 1 hachimaki headband

(like the apprentice chef wears at your neighborhood sushi

place), white with red sun (Japanese flag pattern) flanked by

black kanji that literally read "strive together"![]()

—meaning

"succeed" or "pass"—that express the

learner's aspiration to professional excellence.

—meaning

"succeed" or "pass"—that express the

learner's aspiration to professional excellence.

We then head to Tokyu Hands, which turns out to be a combination of

Pearl Paints and Wal-Mart. (We once again behold the Japanese penchant

for ridiculous names—Tokyu means "Oriental express"

, and only

the good Lord knows what Hands is supposed to convey.) Each of the

store's seven stories is split into three partial levels separated from

one another by a few steps. There are extensive departments for

posters, painting, calligraphy, stationery, dolls, models,

leather craft, paper craft, etc. Looking for nice

Japanese posters, we are surprised to find that Keith Haring and

Roy Liechtenstein posters dominate the selection. The only thing

I find worth buying is a seven-dollar annotated map of Japan with

lots of kanji characters to wrestle with. Cheryl is upset

that I got a sexy comic and a map while she hasn’t yet

gotten the armless kokeshi doll that she says she wants so

badly. This is intriguing, since it’s the first I’ve

heard of such a desire. I tell her that, unbeknownst to her, I

have been settling for certain items because they are

adequate; I have not indulged my heart’s desires. I bought a

map because it looked interesting and was acceptable, not because

I got off the plane saying, "Shit, my life would be complete

if only I could buy a map of Japan in Japanese."

, and only

the good Lord knows what Hands is supposed to convey.) Each of the

store's seven stories is split into three partial levels separated from

one another by a few steps. There are extensive departments for

posters, painting, calligraphy, stationery, dolls, models,

leather craft, paper craft, etc. Looking for nice

Japanese posters, we are surprised to find that Keith Haring and

Roy Liechtenstein posters dominate the selection. The only thing

I find worth buying is a seven-dollar annotated map of Japan with

lots of kanji characters to wrestle with. Cheryl is upset

that I got a sexy comic and a map while she hasn’t yet

gotten the armless kokeshi doll that she says she wants so

badly. This is intriguing, since it’s the first I’ve

heard of such a desire. I tell her that, unbeknownst to her, I

have been settling for certain items because they are

adequate; I have not indulged my heart’s desires. I bought a

map because it looked interesting and was acceptable, not because

I got off the plane saying, "Shit, my life would be complete

if only I could buy a map of Japan in Japanese."

Back on the train, there are more lifeless people. Even if they’re full of personality, all conversation seems to grind to a halt as soon as they set foot on the train. If Cheryl and I laugh, they stare at us. We emerge at a station near the Ginza and decide to visit the Sony Center, which—we have been told—is stunning. There is quite a to-do outside the Sony Center: security officers protect a suited sexagenarian (perhaps the president of Sony) from an onslaught of official press photographers and onlookers while the Asahi beer ad—featuring a life-sized gorilla doll that appears to be climbing the side of the building—looms overhead. Entering the facility, we see a five-level showroom of breathtaking flat panel televisions (Japanese signal only); notebook computers (running Microsoft Windows, of course) that offer the ability to mix and match kanji and romaji filenames; and the most incredibly lifelike video games (which, I’m sure, will seem incredibly non-lifelike two years hence). To the uninitiated, all of this may constitute a technological wonderland, but as a computer maven who designs state-of-the-art network computing devices for a living, I really couldn’t find cause to get excited.

We decide that, if Cheryl wants a Japanese doll, we will look for a nice one, not for some random piece of dreck hawked by a street vendor. We enter a lovely Ginza department store called Mitsukoshi, where the beautiful lady at the reception counter tells us that the Japanese souvenir shop is on level B3. Riding escalators down three levels, we find the souvenir shop. We discover a selection of breathtaking silk-clad porcelain dolls depicting kabuki characters, clad in precisely sewn silken garments. For reasons of practicality (specifically, how to get the puppy home without it shattering), Cheryl chooses a seventy-dollar doll that will fit in a suitcase rather than a thousand-dollar doll that could barely fit inside an adult Galapagos tortoise if you first scooped out its intestines and spleen and such. I also choose a nice black cotton yukata sporting white and gold calligraphy—which will make a unique bathrobe—for about forty dollars. While one staff member takes the greatest care in wrapping our merchandise, another staff member discreetly disappears with our cash and returns with change.

Now, we had heard that one can assemble a free meal on foot by sampling the foodstuffs on the lower levels of the department stores (in this case, levels B1 and B2). This is not true. It may have been true before the recession hit, but the only samples you can get for free nowadays are vegetables, including a wide assortment of fresh and pickled Japanese vegetables and fairly decent Korean-style kimchi. (The Korean food is spicier and more delicious at home.) We hunted high and low for free fish or free meat, but there was none to be found—unless you drive up alongside a farm animal and take a chomp out of its flank.

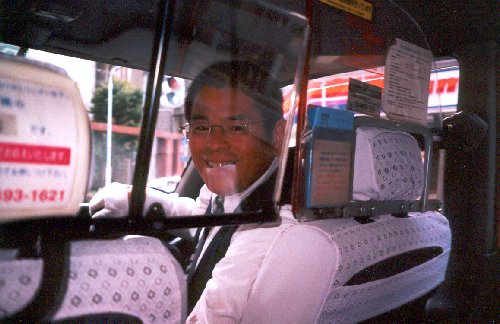

After our lengthy day, tightwad Cheryl consents to allow us to take a taxi back to the hotel through the rush-hour traffic instead of tramping through the trains and subways yet again. The taxi driver, who wears white gloves and has carefully covered the passenger seats with lacy tricot:

only charges ¥820 for a ride of just under two miles.

On the way back to the hotel, we see the first

gas station that we’ve seen—labeled

"rock oil"

, even though gasoline

is obviously not oil, to distinguish the station’s offering

from edible oils. Rather than a stand-alone enterprise (even

Manhattan has room for those), this one is carved out of the

street level of an office building, and gas lines descend from

the ceiling rather like the oil lines at Jiffy Lube. The taxis

are all high-end cars: Toyota Crown Comfort, Nissan President

Royal Saloon, Nissan Cedric. Only the wealthy drive a Mercedes,

which is quite the status symbol here—though not exactly

rare. I only saw one BMW while in Japan.

, even though gasoline

is obviously not oil, to distinguish the station’s offering

from edible oils. Rather than a stand-alone enterprise (even

Manhattan has room for those), this one is carved out of the

street level of an office building, and gas lines descend from

the ceiling rather like the oil lines at Jiffy Lube. The taxis

are all high-end cars: Toyota Crown Comfort, Nissan President

Royal Saloon, Nissan Cedric. Only the wealthy drive a Mercedes,

which is quite the status symbol here—though not exactly

rare. I only saw one BMW while in Japan.

We stop for a quick meal and, for the first time, find the food to be less than superlative. We also notice for the first time that water is not provided unless you ask for it (the default is green tea) and, for that matter, neither is a napkin—which the restaurateur fixes by matter-of-factly marching into the toilet and retrieving crude brown paper towels. (Fancier places did give us a moist cloth hand towel.) To my surprise, I see a Sikh walk past us on the street. (Although I’ve seen Indians, this is the first Sikh, who must draw considerable attention from the Japanese thanks to his prominent turban and his "five Ks"—kara [steel bracelet], kirpan [dagger], kesh [uncut hair], kangha [comb], and kachh [battle briefs]—all of which I learned about in John Bowker’s stunning World Religions [London: Dorling Kindersley, 1997].) After eating, we trudge back to the hotel, dead-tired, at 7:00PM, so we catch a bit of the ongoing sumo match and then hit the rack. Waking at 1:00AM, I popped a few VALIUMę, since I was determined to sleep through the night for once—even if such "sleep" was artificially forced upon me by an anxiolytic—but they didn’t do the trick.

We’re up at 5:00AM again. Cheryl tells me that I’ve been waking her, but my perception is that she is having at least as much trouble sleeping as I am. On the other hand, I’m accustomed to sleeping seven hours per night, whereas she gets nine. I had my first dream, meaning my first decent REM sleep (I always remember my dreams in vivid detail, though I elect not to share them here).

I pick up the phone out of curiosity and note that the dial tone is a broken G, not a steady F-A chord like ours. I am dreaming of a delicious beef-salmon-pickles-rice breakfast at Yoshinoya. The cafe is bustling at 6:00AM when we enter, and we receive a strong "irasshaimase!" greeting both there and at the am pm convenience store where we stop next for some bottled water before hopping on our next tour bus. Like the last one, this tour starts with a hotel lobby pickup and a transfer at the Hato bus terminal at Hamamatsucho. We each get a darling sticker of a Buddha to display on our shirts. Our guide is a young Japanese lady, Naoko, with a delightful sense of humor—indeed, she laughs almost continually, so much so that I begin to question her IQ. We dutifully rally behind her as her green flag, emblazoned with the stirring figures of Donald and Daisy Duck, flutters in the wind. Naoko will guide us through Tokyo station for our train ride to Kamakura, and she counts us continuously (unlike the last several tour guides, apparently) so that we don’t end up appropriated, sliced, and vinegared on a bed of rice. Now, I knew that yon is used instead of shi for "four," since shi also means "death," but I did not know until today that nana is used for "seven" instead of shichi. The explanation is a simple one: ichi (one) and shichi are too hard to distinguish over the phone. (Germans do the same sort of thing, using zwo for "two" to steer clear of confusion between the rhyming zwei and drei.)

Heading to Kamakura on the Pacific coast by train, we again see power lines absolutely everywhere. The proliferation of above-ground power lines is testimony to Japan’s ever-present earthquake risk, which makes underground line installation unjustifiable. Passing through Yokohama and down to Kamakura, everything has a 1940s look—except for that whitewashed goddess, whose head stands out among the trees. Every free-standing iron structure over 150 meters tall—just like the Tokyo tower—is painted white and vermilion per aviation law.

We get off the train at Hase

(“long valley"

). The

pronunciation "Hase" doesn’t match the kanji,

so hiragana (it’s called furigana in this

case) is supplied so that even adults can figure out how to

pronounce it. Although the houses are right up against the

road—and, of course, tiny—they still cost $300,000. In

Japan, we are told, it is desirable to be near the tracks because

of the extreme convenience in this commuting-happy nation. I find

the noise to be a detriment, to which Naoko says, "If you

don’t like noise, then you cannot live in Japan."

). The

pronunciation "Hase" doesn’t match the kanji,

so hiragana (it’s called furigana in this

case) is supplied so that even adults can figure out how to

pronounce it. Although the houses are right up against the

road—and, of course, tiny—they still cost $300,000. In

Japan, we are told, it is desirable to be near the tracks because

of the extreme convenience in this commuting-happy nation. I find

the noise to be a detriment, to which Naoko says, "If you

don’t like noise, then you cannot live in Japan."

We schlepped first to the colossal Buddha image. I have seen

my mother’s pictures of it, serenely meditating under a

brilliant yellow sky—evidence of the meteor that had shortly

before vaporized the dinosaurs and thrown their particulates and

other ejecta into orbit—but the real McCoy was quite

imposing. The stele in front of the Buddha, on which is carved

the original Chinese form of the character for "country"  instead of the Japanese form

instead of the Japanese form  , gives only the merest hint of the age of

the colossus, which is on the order of 750 years. There is

considerable symbolism in Buddha’s (Gautama Siddhartha was the prince’s real name)

posture, his expression, the gesture of his hands (mudra),

and so forth. You can crawl inside the statue for ¥200 per

person, or ¥100 per nostril, and we do so. After this, we march

through the city streets—mysteriously seeing chicken images

just about everywhere—and up to the Hase Kannon temple.

(They tell me that my "chicken" is actually a

dove—the icon of the city, in which shape famous Kamakura

cookies are vended—but I disagree.) Along these streets, I

see my very first plate (a plastic model, actually) of tonkatsu—breaded

pork cutlet—which, we had been told, is so common in Japan.

Now, Hase Kannon temple was just another temple, with thousands

of red-bibbed Jizo

images aside from the standard statuary, but it also incorporates

some interesting (if tight) gardens and a passageway through a

cavern that is marked "caution—low headroom"

(actually, "head

above—concentrate mind"

, gives only the merest hint of the age of

the colossus, which is on the order of 750 years. There is

considerable symbolism in Buddha’s (Gautama Siddhartha was the prince’s real name)

posture, his expression, the gesture of his hands (mudra),

and so forth. You can crawl inside the statue for ¥200 per

person, or ¥100 per nostril, and we do so. After this, we march

through the city streets—mysteriously seeing chicken images

just about everywhere—and up to the Hase Kannon temple.

(They tell me that my "chicken" is actually a

dove—the icon of the city, in which shape famous Kamakura

cookies are vended—but I disagree.) Along these streets, I

see my very first plate (a plastic model, actually) of tonkatsu—breaded

pork cutlet—which, we had been told, is so common in Japan.

Now, Hase Kannon temple was just another temple, with thousands

of red-bibbed Jizo

images aside from the standard statuary, but it also incorporates

some interesting (if tight) gardens and a passageway through a

cavern that is marked "caution—low headroom"

(actually, "head

above—concentrate mind"

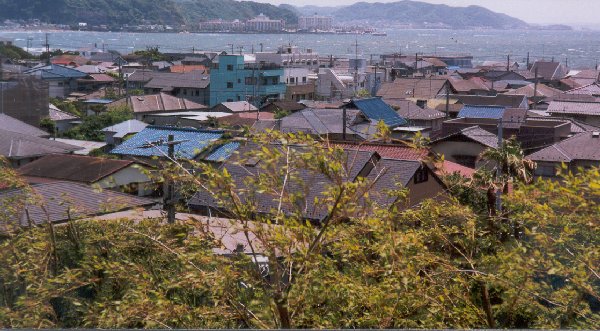

). The elevation of

the temple complex affords picturesque views of this hilly

seaside town that hugs the lunular shoreline, and we note that

houses are packed one atop the other right up to the water’s

edge. Across the inlet, there appear to be some

"luxury" high-rises. I could have gotten a better view

had I fed coins into that free-standing telescope thing at the

edge of the cliff for a quick peek. (These are the same

telescopes that I used to see at the beach at Sunken Meadow when

I was a little boy. I would ask my father for pennies to feed

into them so I could see across Long Island Sound to Connecticut

while eating my Cracker Jack«—relishing the caramel-coated

popcorn and carefully trashing the peanuts while scoping for my

secret toy surprise.)

). The elevation of

the temple complex affords picturesque views of this hilly

seaside town that hugs the lunular shoreline, and we note that

houses are packed one atop the other right up to the water’s

edge. Across the inlet, there appear to be some

"luxury" high-rises. I could have gotten a better view

had I fed coins into that free-standing telescope thing at the

edge of the cliff for a quick peek. (These are the same

telescopes that I used to see at the beach at Sunken Meadow when

I was a little boy. I would ask my father for pennies to feed

into them so I could see across Long Island Sound to Connecticut

while eating my Cracker Jack«—relishing the caramel-coated

popcorn and carefully trashing the peanuts while scoping for my

secret toy surprise.)

Then it’s off to lunch at a "Spanish" restaurant. The owner is a Japanese who visited Spain, not a Spaniard, so it does not compare to the brilliant Las Tapas in "Old Town" Alexandria, Virginia. It looks authentic enough, with its de rigueur bullfight posters and decorative flasks of fine Spanish wine. Once the food arrives, we start to really wonder what part of Spain the owner visited, since the meal started with bread and butter and moved on to pasta cacciatore; chicken breast with oregano; and lowly yellow cake. At least the company was pleasant: we sat with an older nisei couple from Los Angeles who were very chatty and educated. We soon boarded another train. Indeed, we got on and off the local railroad a number of times, and I honestly don’t recall which temple was at which station. I only remember that my feet were very tired despite my very comfortable suede Birkenstock clogs, which were thoughtfully designed with anatomical precision for the discriminating yuppie foot. The train, oddly enough, featured a dolphin logo, which is no doubt reminiscent of the dolphin’s legendary efficiency as a means of land transportation.

Our subsequent trek brought us to another shrine. This one is

called Tsurugaoka Hachiman-gu, and the path leading to it

occupied a parkway down the middle of the main street of the

village. The entrance is marked by the standard torii archway, flanked

by a pair of Chinese lion dogs (the komainu with open mouth

and its close-mouthed karashishi partner). We are told that

this shrine is a popular springtime and autumn destination. To our

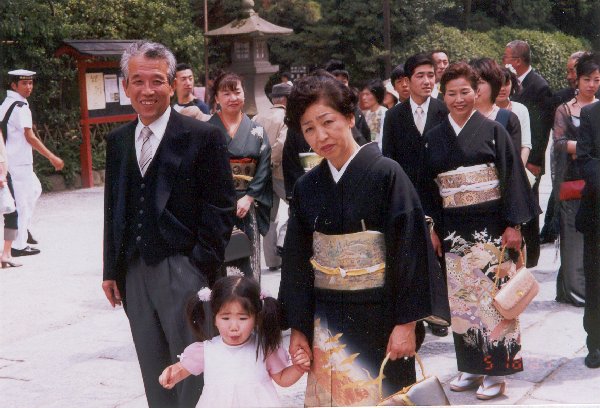

delight, we see the bride and groom in a Shinto wedding being carted by jinrikisha

(“man power vehicle"

![]() ) to the shrine.

) to the shrine.

Bold as a shaygets, I stand with the wedding photographers and snap pictures of the spectacularly attired wedding party (the groom is careful to make the "peace sign" for his photo):

while Cheryl shoots the splendid kimonos sported by female wedding guests.

The shrine incorporates the usual metal rack on which people

hang prayers inscribed on postcard-sized ema tablets

("picture horses"

, so named because the

faithful originally presented live horses to the temple before

switching to pictures of horses—and, nowadays, the pictures

don’t even show horses). The grounds around the shrine are

beautiful, featuring ponds that are home to ornamental koi

carp and small turtles; islands connected to the mainland by

creaky wooden bridges; bamboo, weeping willow, and water lilies.

Although the koi are solid black or golden orange, Naoko

tells us that these are every bit as valuable as the multicolored

koi that many collectors prize. Among the crowds here, we

stumble across a group of Japanese navy recruits.

, so named because the

faithful originally presented live horses to the temple before

switching to pictures of horses—and, nowadays, the pictures

don’t even show horses). The grounds around the shrine are

beautiful, featuring ponds that are home to ornamental koi

carp and small turtles; islands connected to the mainland by

creaky wooden bridges; bamboo, weeping willow, and water lilies.

Although the koi are solid black or golden orange, Naoko

tells us that these are every bit as valuable as the multicolored

koi that many collectors prize. Among the crowds here, we

stumble across a group of Japanese navy recruits.

We have some free time on Kamakura’s principal shopping

street before we return to Tokyo.

The shops vend your usual tourist tchatchkes, but we still find

some lovely painted shoji (folding screens) to buy.

Heading back to the train, we note that people stand patiently in

line to enter the train, waiting until everyone is off the

train before advancing. I was taught to say orimasu if I

must dash into or out of the train, but I haven’t really

needed to use it, though I use it anyway to show off my proficiency.

Down here—unlike in Tokyo—signage

in English is quite limited, so my knowledge of kanji

is essential, not merely handy. The signs include a most peculiar

one (entirely consonant with the predilection of the Japanese for

choosing the poorest names for businesses) that marks an

establishment as a branch of the famous "Not Two Houses"

chain.

chain.

Naoko is an old hand on these trains. When she shows us a

diagram of the train network that serves the Tokyo-Yokohama metropolitan area, we almost

faint. She jokes, “Do you think it’s too complicated? I

don’t think so!” We tell her about how we bought JR

rail passes for $225, and she congratulates us on our research

and foresight: a native can pay that much for a single round-trip

ride on the shinkansen, or “bullet train” (it actually means,

quite simply, “new trunk line”

).

Naoko tells us that many of the train lines are seventy years old and that

they have become a vital link to the capital—the only place to

live if you really want to be a mainstream economic

success.

).

Naoko tells us that many of the train lines are seventy years old and that

they have become a vital link to the capital—the only place to

live if you really want to be a mainstream economic

success.

Diversion on Japanese language: The rules are broken all the time. Even though hiragana is used for Japanese endings and katakana for foreign words, the electronic signboard in the train uses katakana. Why? Because it’s easier to display the simple, angular shapes on a low-resolution LED screen. Learning more characters, I find that the "water" radical plus "soldier" phonetic means "beach"

, which is the hama in Yokohama. We also find that, even though Japanese city names are two or three characters long, we often use only one character as a shortcut for the name. So, for example, the street that I thought said "Capital Beach Boulevard" actually says "Tokyo-Yokohama Boulevard.” The elevator signage, which should be simple, harbors even more surprises: the kanji for "name" represents "individual," so "capacity 11 persons" is expressed as "firm (i.e., strictly) membership 11 names"

, while "no smoking" is expressed as "tobacco prohibit"

.

The one thing that facilitates learning is that nearly every name—whether of places or of people—is nature-oriented and simplistic, for example, the Aomori ("Blue Forest"

), Yamaguchi ("Mountain Pass"

), and Hokkaido (“North Sea Way"

) prefectures (akin to U.S. states). Sections of Tokyo include Chiba (“Thousand Leaves"

), Ojima ("Big Island"

), Hakusan ("White Mountain"

), and Morishita ("Lower Forest"

). No one can tell me why two sections of Tokyo are called Harajuku (“Field Hotel"

) and Shinjuku ("New Hotel"

)—when they have no more or fewer hotels than any other section—or why Meguro ("Eye Black"

) is called that. Next linguistic diversion or previous

Cheryl has a crazy idea: she wants to head down to the Asakusa Kannon temple to see the Sanja Matsuri festival, where literally millions of crazed worshipers will be toting portable shrines through the streets on palanquins. I convince her that this is asking for trouble and that we should skip it, contenting ourselves instead with a quick dinner and a meander down a mercantile alley to check out the motorcycles parked on the sidewalk and the stray cats climbing trees to hunt for birds. The shops in the alley seem a bit pricey: I can’t imagine why this seemingly run-of-the-mill bicycle should go for $3,000. I’ll be sure to think about it while lying in our tiny bed, inspecting the backs of my eyelids.