TRAINS, TEMPLES, AND HORDES—GOZAIMASU!

Bruce David Wilner

July 2001

ABSTRACT: This essay describes our adventures in exotic

Japan in May 2001. It focuses on the fascinating cultural aspects

of Japan, sometimes at the expense of routine descriptions of this

attraction or that. Frequent sidebars delve into various things

Japanese—subjects as diverse as currency, language, clothing,

the geisha subculture, and proper names. (The sidebars on

the Japanese language are hyperlinked together so that you can navigate

through them—ignoring the rest of the material—if you're

particularly interested.) Selected photographs from our set of 700

or so appear throughout the site. We learned not

only that standard preconceived notions are untrue,

but also that authoritative "corrections" of

those notions are often equally untrue! Please take your time to

enjoy the site, and e-mail your comments to me or to my wife, Cheryl. (She

planned the whole affair; I merely brought my wallet, gullet, and

sarcasm.) Thanks are extended to ![]() (ZhongWen.com) for their

nonpareil library of online Chinese character GIFs and to JASC Paint Shop Pro

for helping me to Japanize them.

(ZhongWen.com) for their

nonpareil library of online Chinese character GIFs and to JASC Paint Shop Pro

for helping me to Japanize them.

SUN |

MON |

TUE |

WED |

THU |

FRI |

SAT |

15 |

16 |

17 |

18 |

19 |

||

20 |

21 |

22 |

23 |

|

||

As long as I can remember, I’ve wanted to go to Japan. My mother was there in 1954 when the place was overrun with American servicemen and just getting there required a twelve-day boat journey from San Francisco (on which, as I seem to recall the story, she sat next to George Burns while watching Dr. Seuss’s The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T, which treats the psychedelic adventures of young Bart, a beanie-topped, saddle-shod boy trying desperately to escape from the Happy Fingers Piano Institute). The images that come to mind are well known: exotic land, east meets west, newborn economic giant; fabulous wealth, rooftop golf courses, and indoor ski lifts; geisha, sumo, and sushi. My exposure to Japanese culture—other than from books—consists of the 1970s Broadway musical, Pacific Overtures, starring Mako; Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Mikado; and a dreadful, late 1950s B-movie, Majin—Monster of Terror, about a daimyo whose atrocities (plus the townspeople’s prayers) cause a colossal stone idol to come to life, establish justice, ensure domestic tranquility, and hammer a giant spike through the guy’s chest. But the facts tell me that, only 150 years after their first large-scale exposure to the West (and 50 years after being annihilated in World War II), Japan has emerged as a technological giant that challenges the United States for global economic supremacy. What will it really be like?

Cheryl has planned for this trip for months. There’s a mystique about Japan that gives the tour companies the idea that they can charge arbitrarily high prices and that suckers will flock to them. We learned in Israel that "the only difference is the hotel," and what difference does that make if you spend all day touring and return to your room with barely enough strength to crawl into bed and turn the lights off? As long as it’s clean, it doesn’t really matter: just recognize that you’re not going to have a luxurious stay in your very own king-size bed. This is not the United States. Nothing is. Deal with it.

Trip day is finally here. We dress and don our passport belts

that fit under our shirts. There was no taxi this time—we

drove ourselves to BWI for American's ![]() 6:00AM shuttle to Kennedy. Naturally, we

start the day with a fuck-up: while I had gone to National

several weeks ago to pick up paper tickets for the long-haul leg of

the flight (Delta from Kennedy to Tokyo Narita), I couldn’t pick up

the BWI-to-Kennedy tickets because Delta had no record of them.

(Cheryl hadn’t told me that they were on American Airlines.)

So, when we got to the airport and the line was already nearly as

big as my ego, I wasn’t happy to hear that the tickets

“had been mailed.” I bitched, yelled, and screamed.

Naturally, Cheryl bore the brunt with patience and grace. The

long and short of it is that we got our tickets and made the

plane. I will never again lose patience with some hapless

customer who seems to be spending forever with the ticket agent

while I’m in that enviable “next” position.

6:00AM shuttle to Kennedy. Naturally, we

start the day with a fuck-up: while I had gone to National

several weeks ago to pick up paper tickets for the long-haul leg of

the flight (Delta from Kennedy to Tokyo Narita), I couldn’t pick up

the BWI-to-Kennedy tickets because Delta had no record of them.

(Cheryl hadn’t told me that they were on American Airlines.)

So, when we got to the airport and the line was already nearly as

big as my ego, I wasn’t happy to hear that the tickets

“had been mailed.” I bitched, yelled, and screamed.

Naturally, Cheryl bore the brunt with patience and grace. The

long and short of it is that we got our tickets and made the

plane. I will never again lose patience with some hapless

customer who seems to be spending forever with the ticket agent

while I’m in that enviable “next” position.

We arrived at JFK with our three

carry-ons (one hand-carry and two backpacks) and had to collect our

huge duffel bag that we had checked through, then schlep the whole

kit and caboodle to the Delta ![]() terminal. Of course, the Port Authority

buses were mighty slow that day, but Cheryl would’t

let me hail a taxi, so we stood there like idiots until

the bus condescended to arrive. Presenting our tickets and

passports to the Delta ticket agent, he noticed

that Cheryl’s surname was “Cohen” on her passport

but “Cohen-Wilner” on her ticket (her surname is now

Wilner, but she is still trying to figure out what her name is

after two years of marriage). This would not do, he said: they

would’t let her into or out of Japan if the names

didn’t match precisely. After typing umpteen cryptic

commands that would have taken one or two mouse clicks on a

properly designed system, Cheryl’s tickets were reissued in

the name “Cohen” to match her passport.

terminal. Of course, the Port Authority

buses were mighty slow that day, but Cheryl would’t

let me hail a taxi, so we stood there like idiots until

the bus condescended to arrive. Presenting our tickets and

passports to the Delta ticket agent, he noticed

that Cheryl’s surname was “Cohen” on her passport

but “Cohen-Wilner” on her ticket (her surname is now

Wilner, but she is still trying to figure out what her name is

after two years of marriage). This would not do, he said: they

would’t let her into or out of Japan if the names

didn’t match precisely. After typing umpteen cryptic

commands that would have taken one or two mouse clicks on a

properly designed system, Cheryl’s tickets were reissued in

the name “Cohen” to match her passport.

The plane ride was uneventful.

I’m not quite sure how I managed to pass thirteen hours

without going completely apeshit. Cheryl befriended some younger

Japanese ladies who gave her advice (Ferengi Rule of Acquisition

#59: “Free advice is seldom cheap”) about what places

to visit. The advice includes the "100 Yen Plaza" in Tokyo and the Tokyo Tower (taller than the

Eiffel Tower that motivated it). I ask them about the Osaka

Aquarium, which would seem to be interesting (it supposedly

showcases a live, fifty-foot whale shark), but they don’t

know what an aquarium is, so I write “ocean animal

shop” (really, “ocean self

move thing shop"

["shop"

because I don’t know the kanji for

"museum"]), admittedly making an error in my rendition

of "animal," and they figure it out. (You'd better get

started immediately learning "self"

["shop"

because I don’t know the kanji for

"museum"]), admittedly making an error in my rendition

of "animal," and they figure it out. (You'd better get

started immediately learning "self"

, "thing"

, "thing"  , and "shop"

, and "shop"

. They occur all

the time in Japanese words and phrases.) That’s lovely, but

they’ve never heard of the aquarium, so they can’t

offer us any useful advice.

. They occur all

the time in Japanese words and phrases.) That’s lovely, but

they’ve never heard of the aquarium, so they can’t

offer us any useful advice.

Diversion on Japanese language: It should be obvious from the start that the Japanese written language is quite a piece of work. We can see that just by considering the first three characters introduced: "self"

, which derives from an abbreviated picture of a nose (because Japanese point to their noses rather than their chests when referring to themselves); "thing"

, which derives from abbreviated pictures of an ox and an elephant (because—believe it or not—an elephant and an ox are both things); and "shop"

, which rather playfully depicts a long-nosed clerk standing behind a counter under a shed. Get the picture? For those who enjoy a puzzle or are mathematically oriented, written Japanese is an absorbing diversion; anyone else should steer clear of it. Next linguistic diversion

The Japanese people are quiet. They sleep readily in this plane while I go out of my mind from the noise and the discomfort. I am a Jap, but the other kind (a Jewish American prince); these folks could sleep through a Judas Priest concert. I find it odd that some Japanese guy is wearing white toe socks (with five independent toe receptacles, like preteen girls wore in the early 1970s) with his cross-strap Birkenstock sandals.

Something happened to Tuesday; I’m not sure what. It has something to do with the International Date Line. We left on Tuesday but arrived on Wednesday. It really excites me to know that our trip home leaves at 3:15PM (the Japanese use 24-hour designations, which delights me but upsets ethnocentric Cheryl) next Wednesday afternoon and arrives at 3:20PM. I guess that means that the plane is only in the air for five minutes!

It’s hard to believe, but the Japanese landscape around the airport consists of trees dotted with buildings. We land and are confronted with JAL planes gaily decorated with characters from Pokemon. I believe that one is a pikachu and the one over there is a charizard. These people are so dorky, as we will find out later on. What they think is cool either was cool thirty years ago at home or was never cool to begin with.

Customs was awfully quick. They asked Cheryl to open the duffel bag because they thought they saw a pipe bomb; it turned out to be a plastic tube in which one can roll up posters or prints for safe, damage-free travel. The officer gave us a big smile and we were Welcome To Japan. There were no luggage-sniffing dogs to be found in this supposedly paranoid country, something that makes me happy since I brought some most interesting substances (including a small emergency supply of OXYCONTIN©) that were not exactly covered by the note that my doctor typed up for me. I figured that they don’t speak English, so whatever looks official should be good enough.

Thanks to a profusion of English signs, we find a Citibank ATM (we had specifically opened accounts at Citibank—which is fairly widespread in Japan—so that we could get money out overseas and thereby save 0.1% on the exchange rate) and take out ¥100,000. There are roughly 125 yen to the dollar, so our withdrawal amounted to roughly $800, but we’ll simplify things by assuming that one yen equals one cent. After successfully negotiating the Citibank ATM, we are experts, so we share our profound knowledge with a visiting Swiss couple who look baffled.

It dawns on us that this airport is chock-full of vending machines and that, in addition to bizarre juices, cold coffee, and odd tea mixes, many of them vend cigarettes. (We had read that some vending machines even offered underwear, but we never encountered any.) We learn later that 60% of adult Japanese smoke cigarettes. This country has the world’s highest life expectancy, so one wonders why they don’t kick the smoking habit and increase their lead. Cigarettes are just so fucking revolting.

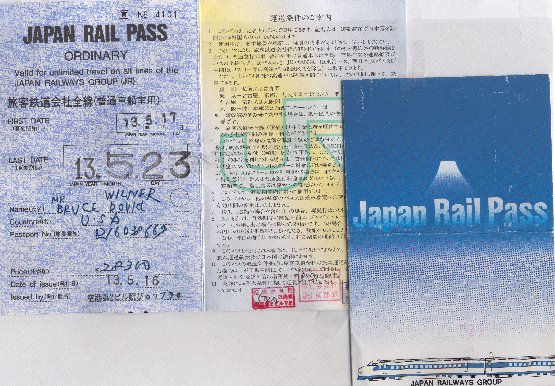

Now it’s time for the train station. We bought Japan Rail ("JR") passes that are only available to foreigners. With such a pass, one can ride anywhere throughout Japan for seven days for a fixed price of about $225 per adult.

Cheryl has done her homework: she knows to ask for the Mount Fuji side of the train and the last seat in the car (behind which, evidently, there’s room for much luggage). The computers are fascinating: they look like those Micros Systems panels you see at Burger King. The man presses keys that are labeled with katakana syllables and then chooses the kanji that pop up from a menu after each keystroke. It is laborious but a brilliant adaptation of our technology to their archaic written language. On the desk behind the clerk, one sees a Victor calculating machine like the ones that were considered quaint in 1970. Before presenting each ticket, the main proclaims "hai!" ("yes!") and then proudly explains his work. Our JR passes and individual reserved seat tickets bear the "year" 13, which, I quickly conclude, refers to the 13th year of the Heisei, Emperor Akihito’s reign (he ascended the throne in 1989). Three years coincide in Japan: the Western year (2001), the Heisei year (13), and the Chinese zodiacal year (the snake, I believe). I waste no time in squirreling away several notes for my coin collection: ¥1000, ¥5000, and ¥10,000 (collectively worth $130). Dates on coins are also indicated in either Heisei year (= year minus 1988) or Showa (= year minus 1925).

Diversion on Japanese currency: The coins in circulation are ¥1, ¥5, ¥10, ¥50, ¥100, and ¥500; the notes are ¥1000, ¥5000, and ¥10,000. Most of the coins bear floral motifs on the reverse, though the ¥10 coin bears a temple on its reverse. Both the ¥5 and the ¥10 show a wreath on the obverse. The ¥5 and ¥50 coins have a hole in the center. All coins are silver-colored except for the ¥5 (gold-colored), ¥10 (copper-colored), and ¥500 (recently changed from silver-colored to gold-colored). The ¥1000 note has a white and turquoise scheme, with some dude on the obverse and a pair of cranes on the reverse. The ¥5000 note has a white and indigo scheme, with another dude on the obverse and Mount Fuji on the reverse. Finally, the ¥10,000 note has a multicolored (but predominantly white and brown) scheme with a traditionally clad dude on the obverse and a pair of Japanese pheasants, or kiji, on the reverse. I kept one of each for my coin collection, where they will sit there, looking unusual and gathering dust, even if they have a combined circulating value over $130.

The toilets at the airport are overwhelmingly Western-style, not Japanese-style. You know what a Western-style toilet is. A Japanese-style toilet consists of a long trench in the ground over which you squat, facing toward the hooded end. It’s actually marginally disgusting.

We ride a reasonably luxurious bus to our hotel. (We had heard that it costs something like $400 for an airport-to-downtown taxi ride, but if you "rough it" by airport bus—requiring you to apply common sense and read plentiful English signs—it costs about $25.) The bus leaves precisely on time, as does every public vehicle in Japan. We pass through "countryside" that reminds me vaguely of the Bronx except that the roofs are strictly Japanese clay tiles. Power lines are everywhere, and golf driving ranges enclosed in thirty-meter mesh walls are almost as common. The driver must stop frequently along the forty-mile trip to pay tolls. The roads are not only narrow here (two lanes each way), but expensive as well: we later learn that the 330-mile trip from Tokyo to Kyoto sets one back more than $100 in tolls. (A new bridge that joins Honshu [the main island] to Shikoku costs $27.) The expressways have dull names, e.g., "Expressway No. 1." The sights are so alien. I am gawking at the kanji on the vehicles and road signs.

(The fact that I can read several hundred kanji

made the trip so much more rewarding: not only did I actually

have a clue what I was looking at—for example, how this truck

bragged with utmost pride that their birds were domestically

produced ["nation inside produce"![]()

![]()

] rather than U.S.

imports—but the signs were so funny because they revealed

the remarkable unoriginality of Japanese business names and the

bizarre ways in which the Japanese mind combines words to convey

abstract ideas—more on that later.) There are relatively few

billboards. We presently pass Tokyo

Disneyland (“Dijunii Ranzo"), which is

right smack up against the next business without so much as a

tree to buffer it. We see white license plates with dark green

text, black license plates with white text, and yellow license

plates with dark green text. (We come to understand all of this

later.) We also see a fair number of very tall Ferris wheels (we

learn that the Japanese are nuts about these, even riding wheels 500

feet tall) and—once we get into the Tokyo conurbation—frightfully

alien architecture (I would learn more than a year later that this is

the Fuji TV headquarters):

] rather than U.S.

imports—but the signs were so funny because they revealed

the remarkable unoriginality of Japanese business names and the

bizarre ways in which the Japanese mind combines words to convey

abstract ideas—more on that later.) There are relatively few

billboards. We presently pass Tokyo

Disneyland (“Dijunii Ranzo"), which is

right smack up against the next business without so much as a

tree to buffer it. We see white license plates with dark green

text, black license plates with white text, and yellow license

plates with dark green text. (We come to understand all of this

later.) We also see a fair number of very tall Ferris wheels (we

learn that the Japanese are nuts about these, even riding wheels 500

feet tall) and—once we get into the Tokyo conurbation—frightfully

alien architecture (I would learn more than a year later that this is

the Fuji TV headquarters):

and the most complex systems of elevated pedestrian walkways that can take you to any corner of a multi-street intersection.

We have to stop at this hotel and that hotel to deliver other guests; this bus isn’t exactly a limousine (of course, an American airport “limousine” is merely a bus that makes multiple stops before yours but happens to have the word “limousine” painted on it). We see that Tokyo’s side streets are quite narrow, with many buildings to match.

Each hotel has immaculately dressed, white-gloved staff who direct the buses around the entrance plaza and back onto the city streets with the precision of an airport tarmac worker. They also bow with the grace of a danseur when you enter or leave their facilities. But it is practiced, studied grace more than innate talent—the same phenomenon we witness in, say, a technically excellent Japanese piano prodigy or her precocious Olympic gymnast countryman.

We discern by driving all over and up and down and in and out that this is one colossal city. The stratospheric shopping malls and endless high-rise complexes are intimidating in the same way that Co-Op City in The Bronx must have been forty years ago. Yet, it seems less crowded and more livable than New York: certainly, it has only twice the population in three times the area. Although the alleys are tight, the main streets are quite wide and often lined with attractive trees.

We get to our hotel, which is near Shiba Koen ("Lawn Park"

) in

Shibaura (Lawn Inlet

) in

Shibaura (Lawn Inlet

)

cho of Minato (Harbor

)

cho of Minato (Harbor  ) ku of Tokyo

("Eastern Capital"

) ku of Tokyo

("Eastern Capital"

), near a large

torii called Daimon (“Big Gate”

), near a large

torii called Daimon (“Big Gate”

)

that affords a peep at the base of the Tokyo Tower. My wife has done

a masterful job of hotel selection: although the place is not opulent

(lobby excepted, of course), the price is right—about $80 per

night—and the location is positively outstanding. Notably, though

the area lacks that grungy Manhattan look, it is way, way downtown.

)

that affords a peep at the base of the Tokyo Tower. My wife has done

a masterful job of hotel selection: although the place is not opulent

(lobby excepted, of course), the price is right—about $80 per

night—and the location is positively outstanding. Notably, though

the area lacks that grungy Manhattan look, it is way, way downtown.

We drew room 1108 on the eleventh

floor in the hotel annex (labeled “separate building"

as opposed to the

"main building" [literally, "root

building"]

as opposed to the

"main building" [literally, "root

building"]

),

so we must enter the hotel, exit the hotel, cross a narrow

street, and enter the annex to get to the elevator that takes us

to our floor. All of the doors are automatic, and they have interesting signs that express "caution: automatic

door" in Japanese fashion (literally, "self move—concentrate mind"

),

so we must enter the hotel, exit the hotel, cross a narrow

street, and enter the annex to get to the elevator that takes us

to our floor. All of the doors are automatic, and they have interesting signs that express "caution: automatic

door" in Japanese fashion (literally, "self move—concentrate mind"

).

).

Diversion on Japanese language: The Japanese have stolen nearly every aspect of their culture from China, and the writing system is no exception. Though Japanese and Chinese are linguistically unrelated, 1945 Chinese characters, known as kanji, form the root of the Japanese written language. These 1945 characters are termed the Joyo Kanji ("customary use Han [viz., Han Chinese] characters"),

. The kanji are quite poorly suited to the Japanese language. Each kanji has two pronunciations: the Chinese-derived on pronunciation and the native Japanese kun pronunciation. Only from experience does one know which pronunciation to use in which contexts. The kanji are augmented by a pair of syllabaries: the angular katakana, used to transliterate foreign words, and the cursive hiragana, used to represent Japanese particles, verb conjugations, etc.—or (in which case they are termed furigana) to aid the reader in identifying exceptional pronunciations of kanji that are neither on nor kun. Roman characters, known as romaji, appear frequently, though they are not part of the Japanese writing system per se. (One sees them, curiously enough, on building signs—for example, the kanji name of a business may be followed by 3F to indicate that it’s on the third floor.)

You can get the gist of a sentence if you can understand the kanji, which are of four types. The simplest are direct pictograms that actually look like the words that they represent—for example, mountain, tree, and sheep. Only a few of these remain in the language. Next are radicals, 217 primitive concept indicators that form the basis of the Chinese dictionary. Two or more pictograms and/or radicals can be combined into co-significs that reflect the synthesis of two concepts: for example, "grain" plus "fire" yields "autumn"

(viz., "the season when one sets fire to the harvested grain"), and "insect" plus "leaf" yields "butterfly"

(viz., "the insect with wings like leaves"), while the same "insect" coupled with "work" means "rainbow"

(which makes perfect sense if you know the Japanese etiologic myth about the origin of the rainbow). The underlying poetry of such combinations is often quite beautiful and philosophic. Finally—and, unfortunately, 90% of the time—a radical forms a phonetic or loan word combination with another character. This is where the shit hits the fan: for example, the radical for "child" (which vaguely looks like a tiny baby bundled up) plus "melon" to its right yields "orphan"

—because orphan is the word that relates to the concept of "child" but sounds (in Chinese, not necessarily in Japanese) like "melon." The schoolchild must memorize 1700 such combinations: there is no shortcut.

Maybe the system isn’t as dreadful as it sounds, since—even though there are only 26 letters in our alphabet—a highly educated English speaker may have memorized 50,000 ways to combine these letters into words. In particular, as cumbersome as it is, the Japanese writing system is less complicated than ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics, which additionally support an alphabetic mode whereby characters represent individual consonants or diphthongs. Almost incredibly, while only 1945 kanji are required to graduate from high school, some 3000 are typically needed to understand a college textbook. Thus, unlike his American counterpart, a Japanese college student is still learning how to read and write Japanese.

Now, the Chinese treasure fine calligraphy. A printed character in a dictionary or book can only capture a fraction of the dynamism of a masterfully handwritten character. The Chinese are so devoted to the beauty of the written word that, ideally, they never chuck handwritten material in the trash, preferring to burn it amid much ritual. It seems ironic, then, that the Japanese (and, recently, the Chinese) have "abbreviated" some characters, simplifying certain stroke sequences and many de rigueur hooks and serifs, resulting in a rather bland, unattractive appearance. One wonders what additional deformations will occur over time and whether what emerges from the kanji a century from now would even be recognizable by today’s reader. Many deformations have already occurred over time, so the pictographic roots of a character are often more plainly evident on a three-thousand-year-old Chinese bronze than in today’s newspaper.

Good introductory discussions can be found in two delightful books: Diane Wolff’s Chinese for Beginners (New York: Barnes & Noble, 1974) and Len Walsh’s Read Japanese Today (Rutland, VT: Charles E. Tuttle, 1984). Kanji Kanji (Tokyo: The East Publications, 1983) offers a less structured, more anecdotal approach but is nevertheless highly informative. The brave of heart can try Bernhard Karlgren’s Analytic Dictionary of Chinese and Sino-Japanese (New York: Dover, 1974) or Father L. Wieger’s Chinese Characters (New York: Dover, 1965), which are enthralling but quite scholarly. Next linguistic diversion or previous

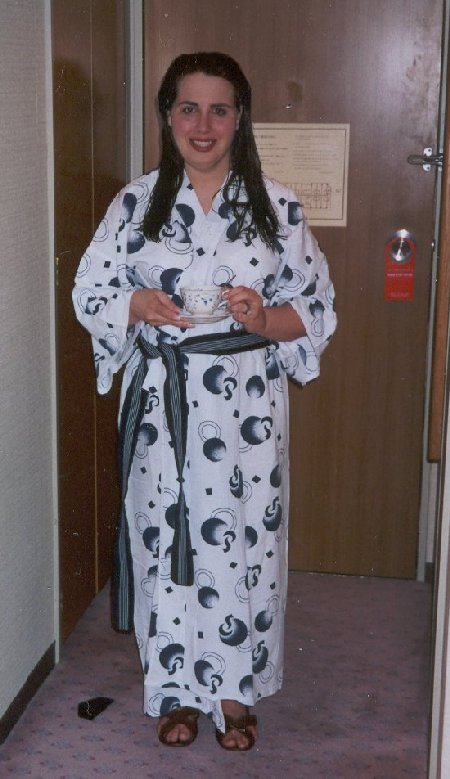

The view from our room is of the next high-rise, which is about twelve feet away. Not since the west side of Manhattan has one seen a lousier view through an ostensibly depression-relieving window. Our room is small and has a low double bed and buckwheat husk pillows like the ones you see on that infomercial. A single blond wood panel that serves as a headboard also controls alarm clock, air conditioning, and radio (choice of three muzak stations). A cheap cotton yukata robe (always patterned in white and blue) and grandpa-style cross-strap "toilet sandals" have thoughtfully been provided for each of us.

(In Japan, one wears shoes that are designed specifically for bathrooms. They have a fixation about foot etiquette: great importance is assigned to feet, even more so than to gonads. Shoes are for "dirty" areas, and socks or bare feet [equivalent in gentility] are for "clean" areas. They haven’t reasoned this out too well, since sharing floors with other barefoot people can spread various diseases, but I guess epidemiological aspects were not of concern when the Imperial Foot Laws were codified.) The toilet is awesome: it has "big" flush and "little" flush modes (that’s all the detail the kanji provides), depending upon what you’ve done, and it has a nice button to press that sprays hot water against your anus with some force in case you’re messy after the gastroenterologic strain of a long flight and Delta Air Lines food.

We never unpack; it’s more fun to fight and scream about what we cannot find and how often we have to unlock and relock our luggage. This occasionally degenerates into stomach-poking and nose-squeezing, but mostly it’s just yelling.

It’s time for dinner. We boldly venture forth, expecting people to point at the funny-looking Caucasian giants, but they don’t do so. I am looking at the cars, and I find that my Lexus ES-300 is a "Toyota Windom" and that the spiffy Lexus LS-430 is just a lowly "Toyota Celsior." They have more varieties of Toyotas and Nissans here than you can shake a stick at. (They all have the steering wheel on the right-hand side, since one drives on the left in Japan. Also—and I’m at a loss to explain this—nearly every car is black, white, or silver—except for a certain fleet of taxis that are all aquamarine.) This is a business area, and people are busily rushing to and fro. Nearly identically clad businessmen who part company on the street bow lightly to one another—they do not shake hands. We see our first koban, or police booth (there are many in Tokyo), and the policeman proudly poses for a photo. You need him to find your way, since very few streets have names: an address consists of a ward (ku), a section of the ward (cho), and three hyphenated numbers that mean who-knows-what. Need to find an address? Ask the policeman (who greets you with "Hai!" ["yes" or "ready"]); he will instantly produce a detailed neighborhood map and provide explicit directions.

Nearly every office building and/or brownstone seems to have a

street-level restaurant. The older-looking ones have streamers or

curtains (noren) hanging down over the entrance that, on a windy day,

slap you squarely in the face. Many businessmen (but evidently

not women!) eat quick dinners at these places, which are

attractively priced (tipping never required). The food is

of quality but not Lucullan. The businessmen at one place also

drink beer merrily and rowdily, particularly at this restaurant

that says "Autumn Field" in Japanese ("Akita"

, like the dog). We are

intimidated by the place, which features throngs of drunken

customers jostling for the attention of the overworked,

rough-looking staffers, so we try another. We drag the

proprietress outside to point to the plastic display models

(whoever makes those models—which are outside nearly every

restaurant in Japan—must be a billionaire) and end up with

delicious shrimp tempura (my wife says it’s the best she

ever had) and a large bowl of tempting beef and soba

(buckwheat noodles) soup for less than nine bucks total.

, like the dog). We are

intimidated by the place, which features throngs of drunken

customers jostling for the attention of the overworked,

rough-looking staffers, so we try another. We drag the

proprietress outside to point to the plastic display models

(whoever makes those models—which are outside nearly every

restaurant in Japan—must be a billionaire) and end up with

delicious shrimp tempura (my wife says it’s the best she

ever had) and a large bowl of tempting beef and soba

(buckwheat noodles) soup for less than nine bucks total.

Let’s take a walk after dinner. We find a small park that

houses the Zojo-ji shrine and a statue of

Jizo, the protector god of deceased and stillborn infants,

whom grieving parents have dressed in the customary bright red bib.

We walk past the imposing Tokyo

Tower and presently see some young man march along and post what

appears to be a prostitute’s business card (which looks for

all the world like a baseball card—without the statistics!)

on a lamppost. A most intriguingly designed fire hydrant

("extinguish fire plug"

) access panel on the sidewalk bears a highly

stylized cartoon of Japanese firemen in regalia reminiscent of samurai:

) access panel on the sidewalk bears a highly

stylized cartoon of Japanese firemen in regalia reminiscent of samurai:

), and the sign on

that fence that clearly intends "keep off the fence"

(by literally stating, "upright enter

prohibit stand"

), and the sign on

that fence that clearly intends "keep off the fence"

(by literally stating, "upright enter

prohibit stand"

), as well as on the

truck over there, which delivers "Forest

Perpetual Ox Milk"

), as well as on the

truck over there, which delivers "Forest

Perpetual Ox Milk"

(it turns out that

"Forest Perpetual"—Morinaga—is the owner's name). (I find it

astonishing that such a modern culture can flourish using a

pictographic system so utterly primitive—"milk"

(it turns out that

"Forest Perpetual"—Morinaga—is the owner's name). (I find it

astonishing that such a modern culture can flourish using a

pictographic system so utterly primitive—"milk"  , for

example, being composed of a mother's hand

, for

example, being composed of a mother's hand  clutching

her infant

clutching

her infant  to her breast

to her breast  —that

it seems scarcely more advanced than the cave paintings of

Altamira and Lascaux!) With such monumental literary

accomplishments under our belts, we head back to the hotel and

hit the sack, utterly exhausted, at 6:00PM.

—that

it seems scarcely more advanced than the cave paintings of

Altamira and Lascaux!) With such monumental literary

accomplishments under our belts, we head back to the hotel and

hit the sack, utterly exhausted, at 6:00PM.

We both awoke completely refreshed at 1:00AM. The coffee machine has a magnetic plug. Isn’t that odd? Groping around over the bed, I discover a Gideon bible (New Testament only) in Japanese and "The Teachings of Buddha" in bilingual Japanese/English. Some of the Buddhist stories—each of which has a moral, of course—are hysterical:

A man hears a voice from a grave that tells him where to find such-and-such treasure. He is terrified and ignores it. His friend, however, carefully attends the voice, which tells him that eight monks will arrive at his house, that he should lead them into a room and conduct such-and-such a ritual, and that they will then turn into gold. He obeys and presently finds himself fantastically wealthy. The first man, jealous at the "luck" of the second man, invites eight monks into his house, locks them in a room, and performs the ritual. The monks get rowdy, break free, and summon the police.

A beautiful woman appears at a man’s house and is welcomed with open arms. She declares herself to be the goddess of wealth. An ugly woman appears next but is turned away. The first woman promptly leaves, indicating that the other woman was none other than her sister, the goddess of poverty, and that only if her sister is also welcome can she stay for any length of time.

One head of a certain two-headed bird observed the other head eating delicious, sweet fruit and became jealous. It decided that it would eat poison to spite the other head, whereupon the whole bird died.

Despite the high-tech toilet, there is no means for drawing

offensive odors away from the bathroom other than our old friend,

time—not even a vent, let alone a fan. We both shower and

notice that a small piece of the mirror remains totally unfogged

(we would see the same thing at our next hotel in Kyoto ["Capital

City"

]). Why can’t

the mirrors at home do this, we wonder?

]). Why can’t

the mirrors at home do this, we wonder?

There’s not much to do at 1:00AM, so we watch CNN live in English and descry a TBS basketball game dubbed in Japanese. I am already starting to sneeze my head off with the alien plant pollens even though I was careful to get my allergy shots before leaving for the trip.

We had read about the

world-famous Tsukiji fish market, so, with nothing better to do,

we marched off into the black. The streets were already alive at

3:30AM with trucks and taxis. We pass the world-renowned Ginza

(“silver mint,” in actuality, “gold similar mint"

![]()

), which looks like a

routine section of Fifth Avenue, though perhaps slightly less

attractive. Rodeo Drive it ain’t. Tsukiji was alive and

kicking with frenzied activity at 4:30AM. The market, not too

different from Hunts Point Terminal Market in the Bronx, was

incredible: an entire city of workers zipping about on this

half-scooter, half-forklift, half-Zamboni (sorry if that’s

150%) contraption and nearly running over our feet; trucks

backing up tight alleys; and hundreds and hundreds of huge tuna

carcasses (they will no doubt become extinct at this rate):

), which looks like a

routine section of Fifth Avenue, though perhaps slightly less

attractive. Rodeo Drive it ain’t. Tsukiji was alive and

kicking with frenzied activity at 4:30AM. The market, not too

different from Hunts Point Terminal Market in the Bronx, was

incredible: an entire city of workers zipping about on this

half-scooter, half-forklift, half-Zamboni (sorry if that’s

150%) contraption and nearly running over our feet; trucks

backing up tight alleys; and hundreds and hundreds of huge tuna

carcasses (they will no doubt become extinct at this rate):

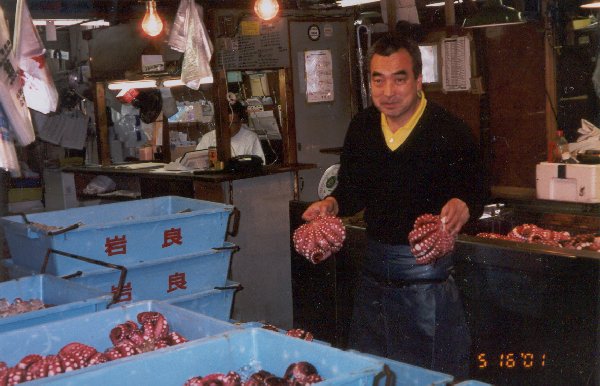

Flash-frozen tuna spill off of trucks right onto the street and are rudely handled with large metal hooks. Stalls sell every kind of seafood imaginable, from fish to clams to scallops to huge prawns to brilliant red octopuses (whose vendor proudly poses for a photo with an octopus in each hand) to spider crabs to (oddly enough) poisonous, inedible-looking stonefish—to whale meat.

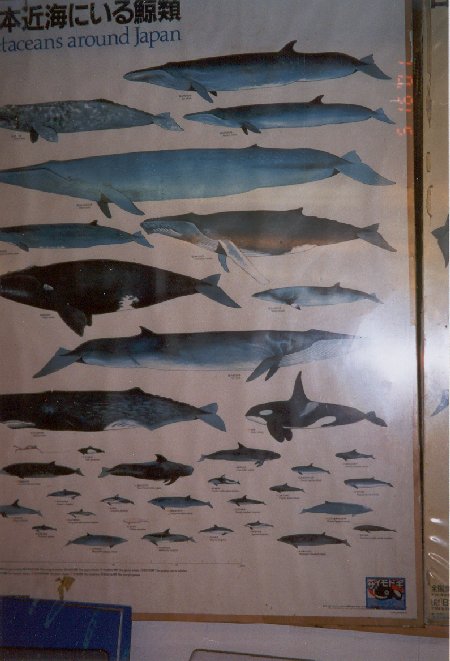

(Never mind the dates digitally imprinted on the photographs, 5/16/01, which contradict the date on which they were taken, 5/17/01—recall that our digital cameras are still operating on Eastern Daylight Savings Time.) The whale shop features two full-color posters of Japanese cetaceans and the choicest cuts thereof:

Leaving the market and entering the satellite city of small shops—outfitted with rude awnings like a Brooklyn fruiterer—we see that the sun is already powerfully ablaze in the sky at 5:00AM, thanks to the fact that there is no daylight savings time in Japan. We stumble across a store that appears to be in violation of every law known to man: he has complete Bengal tiger skins, mounted zebras, and mounted lynxes for sale.

Never mind that: I want to hunt for that sushi place, Sushizanmai, that we passed on the way in. We presently find it and enjoy the best sashimi (raw seafood fillets sans rice or other accoutrements) we have ever tasted. They don’t speak a word of English, and when I try writing Japanese, the owner tells me that this is Chinese, yet he understood it well enough. The house salad consists of tuna chunks in herring roe—Cheryl gives me hers as well inasmuch as she is no fan of any kind of eggs, whether raw or cooked—and the entrees consist of razor clam and eel (for me) and shrimp and salmon (for Cheryl). We are spoiled for the rest of our lives after tasting this overwhelmingly rich, painfully fresh, sinfully delicious seafood that was harvested from the bountiful Pacific literally minutes ago.

Our adventure in Tsukiji ends. We walk back to the hotel, but

it is several miles, so we get tired near the end and hop on the

JR Yamanote line ("mountain hand line"

). I have a staring

contest with the one man on the train who isn’t sleeping,

and I quickly win. We get back to the hotel in one piece at about

7:00AM, well before our first scheduled guided tour, and have

time to duck into the "am pm" convenience store with

its goofy dog’s-head logo and buy a ¥120 gauze surgical mask

(which the Japanese routinely wear over their faces when they

suffer respiratory maladies) just for a lark. The Japanese have a

knack for advertising, but it’s a lousy knack, since the

slogans are so silly. For example, on a lowly can of orange

juice, I find, "We wish to give everyone much more

relaxation—am pm creates the product with the everlasting

desire." We duck into a narrow alley just one block from our

hotel in this bustling business district and find quiet private

houses and an elderly lady who obligingly takes our picture in

front of them. Though it’s only 7:15AM, we feel like

we’ve already had a full day. Jet lag definitely sucks the

big one. At least the sun is shining and the weather is pleasant.

(For nearly the entire trip, we would enjoy days of cloudless

skies and temperatures that ranged from about 60°F to

80°F. Only on the last day of touring did this spell

of gorgeous weather flag.)

). I have a staring

contest with the one man on the train who isn’t sleeping,

and I quickly win. We get back to the hotel in one piece at about

7:00AM, well before our first scheduled guided tour, and have

time to duck into the "am pm" convenience store with

its goofy dog’s-head logo and buy a ¥120 gauze surgical mask

(which the Japanese routinely wear over their faces when they

suffer respiratory maladies) just for a lark. The Japanese have a

knack for advertising, but it’s a lousy knack, since the

slogans are so silly. For example, on a lowly can of orange

juice, I find, "We wish to give everyone much more

relaxation—am pm creates the product with the everlasting

desire." We duck into a narrow alley just one block from our

hotel in this bustling business district and find quiet private

houses and an elderly lady who obligingly takes our picture in

front of them. Though it’s only 7:15AM, we feel like

we’ve already had a full day. Jet lag definitely sucks the

big one. At least the sun is shining and the weather is pleasant.

(For nearly the entire trip, we would enjoy days of cloudless

skies and temperatures that ranged from about 60°F to

80°F. Only on the last day of touring did this spell

of gorgeous weather flag.)

Diversion on Japanese weather: The climate of Tokyo can be compared to that of Virginia: summers are hot, and winters are cool but pleasant. Kyoto is more akin to South Carolina: summers are very hot, and winters are quite moderate. Snow is occasional in Tokyo and rare in Kyoto. They tell me that Hokkaido's weather is more like New England's, and the southern islands' more like Florida's, but I wasn’t there to judge.

It’s time for our first guided tour. (Cheryl lined up a

total of three full-day guided tours [Tokyo, Kyoto, Kamakura]—two with an

evening extension—and one half-day guided tour [Nara], while

we managed the Himeji side trip and other short excursions around

town by ourselves.) All of the guided tours are managed by the

Japan Tourist Bureau, which contracts with a variety of bus

companies. Everywhere we went, we were to bump into the same sets

of buses. We are picked up promptly at our hotel and ferried to

the Hato bus terminal, which is close enough to our hotel (right

by the Hamamatsucho [“beach

pine district" ![]()

—literally,

"water soldier tree public

district"] station on the

Yamanote line) that we could have walked.

—literally,

"water soldier tree public

district"] station on the

Yamanote line) that we could have walked.

(The parenthesized characters on the sign mean "north entrance.")

We are presently assigned to another bus with a pleasant

female tour guide, Yukiko, whose name means "Snow Child"

. She tells us that it

was once very fashionable for women’s given names to end

with –ko, which means "sweet little X,"

but that this is no longer the case.

. She tells us that it

was once very fashionable for women’s given names to end

with –ko, which means "sweet little X,"

but that this is no longer the case.

We drive through various lovely sections of town and are treated to an entertaining lecture about the old and the new. This tour group, in addition to English speakers from the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia, is also peppered with Germans and Dutchmen, so I get an opportunity to try out my passable German and Dutch. Yukiko proudly displays pictures from her own wedding, which include various changes of clothing—starting with a kimono that weighs twenty pounds; is tight to the point of encumbering breathing (we would hear many other guides bitch about the discomfort of the kimono); and costs more than ¥1,000,000. The kimono is accompanied by a traditional wedding hat that is intended to hide the bride’s "horns of jealousy." A kimono is not "proper" unless it is decorated with a mon, or family crest. We conclude that the kimono is dying out, for otherwise why would she show us pictures thereof rather than just let us see one being worn on the street? Cheryl remarks to me that the Japanese seem to have very yellow teeth, and I must admit that this comment is lost on me. Yukiko next tells us that the Japanese follow Shinto when happy (since Shinto favors the here) but Buddhism when sad (since Buddhism addresses the hereafter). It seems quite inappropriate to pick and choose one’s religion based upon the conveniences of the moment, particularly since Shinto is a primitive animistic faith and Buddhism is an advanced polytheistic system. The discussion of the old and the new also touches upon the troubles at the Russian embassy, which we pass: it seems that youngsters frequently picket, based on the fact that Russia occupies one or more of the Kuril Islands north of Japan, and that a network of police spotters is positioned to detect trouble early and secure the embassy when necessary. We again happen past the Tokyo Tower, which is overrun with schoolchildren, who stick heads out of windows and hang from the rafters by their prehensile tails. (Well, perhaps that’s an exaggeration.) The people on the street carry parasols (umbrellas, actually) in the fierce sunlight but do not wear sunglasses. Yukiko tells us that sunglasses are frowned upon. Later, another guide will give us a bullshit explanation about how the superior Japanese eye is not disturbed by brilliant light, whereas the inferior Caucasian eye is photosensitive.

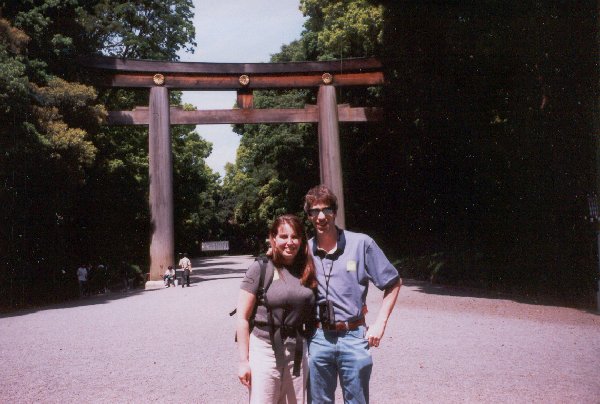

We visit the Meiji shrine, which is the first of many Shinto shrines that we will see. The entrance is marked by a torii built from ancient Japanese cypress trees, which have been the preferred fine building material for many centuries.

The shrine also features stacks of huge sake barrels that are donated to the gods, who evidently like to get drunk.

In fact, the continual drunken stupor of the gods underlies the details of the prayer ritual, which includes bowing twice, clapping twice (to get their attention), orating, and, finally, bowing once. A pot of incense is also provided, and one typically rubs one’s hands in the incense smoke and then on an ailing body part for the reputed sanative effects. Yukiko encourages us to perform one or more of these rites, but I am a Messianic Jew and will not commit idolatry; in fact, it disturbs me that others happy-go-luckily perform the rite as if it’s fun without for a moment considering its implications.

We then drove past the Diet

building, which looks familiar from television:

The juxtaposition of moated castle and megalopolis yielded a unique landscape, both beautiful and ugly, but quintessentially Japan.

It was delightful to walk around the garden and observe the topiary and the carefully tended ponds, but we were not allowed to see any of the palace—other than a vague glimpse of the corner of an eave over yonder. Emperor Akihito, the Heisei emperor, is the 125th in the direct line of descendants from the first emperor, the mythohistorical Jimmu Tenno. Akihito has two sons (both of whom have their own official residences) and a daughter (who lives at the palace with her parents). The wife of the heir apparent, Crown Prince Naruhito, is finally pregnant, and the Japanese people are hoping for a son, who will be second in line to the throne per Japanese rules of primogeniture. If the baby is a boy, his name will end in –hito; if the baby is a girl, her name will end in -ko. In the souvenir shop, I cleverly snap a picture of a beautiful artwork by ducking behind a column while the guards are positioned just so. I wanted to keep as a souvenir the plastic chit with kanji that I was issued upon entrance, but the staff dutifully—indeed, aggressively—collected them upon our exit, so I got jack.

Our next stop is Asakusa Kannon temple; I believe the original name was Senso-ji. We see—to my considerable consternation—that this supposed holy place has turned into a rough-and-ready flea market, leading me to again question the faith of the Japanese.

Some of the faithful are feeding the doves (the guide called them doves, but I call them pigeons, though many languages do not draw any distinction between the two). Others engage in some rite whereby a number is picked at random by shaking sticks (I had a toy like this in the 1960s, called Confucius, as I recall) and a fortune is picked from a drawer bearing that number. If you don’t like the fortune, you put it back and try again! Oh, well: the chicken yakitori procured from a vendor’s stall for ¥500 was the most delicious I’ve ever tasted, the conveniently timed apostasies of the Japanese faithful notwithstanding.

We were taken to a hotel with a stunning panoramic view:

for a supposed "French" lunch, the details of which I scarcely recall. (I only remember that, on the bus, we were asked to choose either a fish, chicken, or beef entrée, whereupon, after we chose one fish and one beef, the guide handed us strips of paper with a cartoon fish and ox, respectively, that we were to set on our plates for the edification of the servers. We felt like we were in nursery school.) We gaze out over the Hama-Rikyuteien—the ancient hunting ground of the shogun—an island of tranquil green (ironically, within earshot of the ear-splitting chaos of the Tsukiji fish market) in the midst of this vibrant city, where Japanese and English signs compete for attention among endless elevated expressways, train lines, and one construction project after another. There may be a recession, but Tokyo’s construction brigades are as busy as those in Reston or Santa Clara were in 1999.

Our ride to and from the hotel took us down several elevated expressways that would have made Robert Moses proud—buildings had obviously been torn down devil-may-care and expressways smashed through. The appearance of tollgates downtown is unsettling and alien. The speed limit on these roads, which are barely better than Brooklyn’s Interborough Parkway, is 100 kph unless otherwise posted (and 80 or 60 is more common in the city). Trucks have three lights in front that light up in proportion to the vehicle’s speed, a convenient aid to police wishing to issue speeding citations. At lunch, Cheryl and I almost break our necks on an unidentified step between our table and the restrooms, since the Japanese do not see fit to post signs warning the unwary to watch his step.

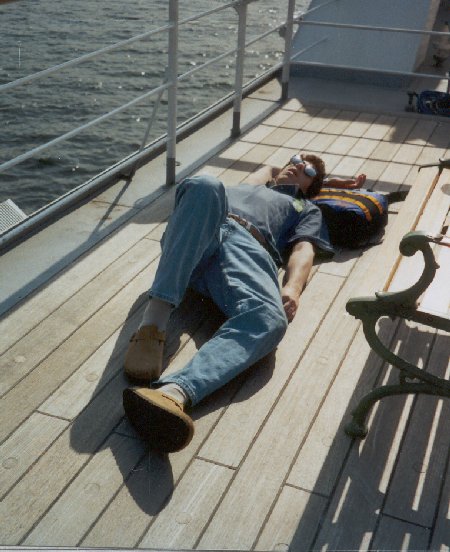

We next took an hour-long cruise

down the Sumida river to sail under the Rainbow Bridge and view

novel architecture manifested in brand-new construction projects

in the Aomi (“blue sea"

) ward east of the

river. (This section, like much of Tokyo,

is built on recently reclaimed landfill.) I had collapsed from

jet lag and spent the entire hour contentedly catnapping in the

sun on the uppermost deck.

) ward east of the

river. (This section, like much of Tokyo,

is built on recently reclaimed landfill.) I had collapsed from

jet lag and spent the entire hour contentedly catnapping in the

sun on the uppermost deck.

Unfortunately, I had to wake up to disembark and then board our tour bus so we could schlep across the Rainbow Bridge (totally fucked up with traffic because of construction in the left lane) to drive around these projects. All I did was worry about whether we would get back to the bus terminal in time to catch our evening tour, which included dinner (oh boy!) and kabuki theater. At least Yukiko gave us a comprehensive lesson on the license plate issue. License plates look like this:

White plates with dark green lettering are for regular vehicles. Black plates with white lettering are for commercial vehicles. Yellow plates with dark green lettering are for low-energy vehicles, and green plates with white lettering are for low-energy commercial vehicles. Pink license plates are for low-energy motorcycles. I think I got all of this correct: it is confusing and haphazard. Low-energy vehicles enjoy certain tax exemptions; otherwise, operating a vehicle in the city is expensive. Though prices may seem cheap compared to what Americans pay, the sales tax exceeds 50% and monthly parking fees are outrageous—not to mention the tolls, which can amount to many thousands of dollars per year. Informative electronic signs pepper the major streets and are automatically updated as weather or traffic conditions change.

All day long, driving all over the city, we only passed two

schools. At one of them, female instructors toting megaphones are

barking instructions at uniformed girls standing barefoot on the

pavement. The guide tells us that this must be some sort of

physical education routine. (Despite the dearth of children, we

did see many, many elderly. The oft-discussed problem of the

aging Japanese society is no joke.) After passing the second

school—late in the afternoon—we drove past numerous

mid-rise housing developments, each apartment advertising its

laundry on a clothesline carefully strung around the satellite

dish. A building that we pass shares its logo (a mother cat

carrying her kitten in her jaws) with a fleet of trucks around

town, and the kanji identifies it as Taku Kyubin, or

“Residential Express Mail” (literally, “house hurry deliver"

).

).

We finally get back to the Hato bus terminal despite the rough traffic and, in clockwork Japanese fashion, are routed onto the next bus, under the care of Daisuke, the only male tour guide we will encounter in our trip. Daisuke conducted us to a delicious sukiyaki with raw egg dinner at a lovely third-floor ryotei (upscale restaurant) just off the Ginza called Suehiro. The restaurant is gorgeously decorated with trees, rock gardens, and traditional tatami rooms (with a space hollowed out under the table to hold your legs so you don’t have to sit cross-legged or [formal style] seiza, which means buttocks resting most uncomfortably on heels) and the dinner was absolutely scrumptious—though my Western appetite was not entirely sated despite two extra helpings of beef.

(I love this picture: my wife is so gorgeous.)

We had read that the Japanese would closely scrutinize our

foot and shoe etiquette, so I’m careful to leave my shoes

pointing toes outward—so I can step into them without

missing a beat upon our exit—and to determine precisely

which floor areas are "clean" (for socks or bare feet)

and which ones a centimeter away are "dirty" (for

street shoes). After having studied so carefully and brought only

pristine socks without the slightest snag, I am sorely

disappointed when it becomes crystal-clear that, despite my

studied savoir faire, our Japanese hosts really don’t

give a fuck about shoes or feet—as long as you have a

pocketful of yen. The dinner of world-renowned Kobe beef (“god’s door ox flesh"

![]()

) costs about $175

here, but I’m sure we had the non-Kobe beef—which, according to the

menu, still sets one back $50 or so for a very modest portion

(per a high-energy, 180-pound Westerner’s standards,

admittedly). Suehiro made me realize that, aside from its dessert

buffet, Sakura Palace in Silver Spring, Maryland (recently

closed, unfortunately), was quite an authentic

Japanese dining experience—except, of course, that Sakura

Palace gives you a Western-size portion that bears a Western-size

price tag. We had a very enjoyable time chatting with a

distinguished issei lady and her half-Japanese, half-Caucasian

adult daughter, both of whom reside in affluent Bergen County,

New Jersey. It was the mother’s first visit to Japan in more

than thirty years and the daughter’s first visit ever, yet

the daughter was having rather an easier time of it than her mom!

) costs about $175

here, but I’m sure we had the non-Kobe beef—which, according to the

menu, still sets one back $50 or so for a very modest portion

(per a high-energy, 180-pound Westerner’s standards,

admittedly). Suehiro made me realize that, aside from its dessert

buffet, Sakura Palace in Silver Spring, Maryland (recently

closed, unfortunately), was quite an authentic

Japanese dining experience—except, of course, that Sakura

Palace gives you a Western-size portion that bears a Western-size

price tag. We had a very enjoyable time chatting with a

distinguished issei lady and her half-Japanese, half-Caucasian

adult daughter, both of whom reside in affluent Bergen County,

New Jersey. It was the mother’s first visit to Japan in more

than thirty years and the daughter’s first visit ever, yet

the daughter was having rather an easier time of it than her mom!

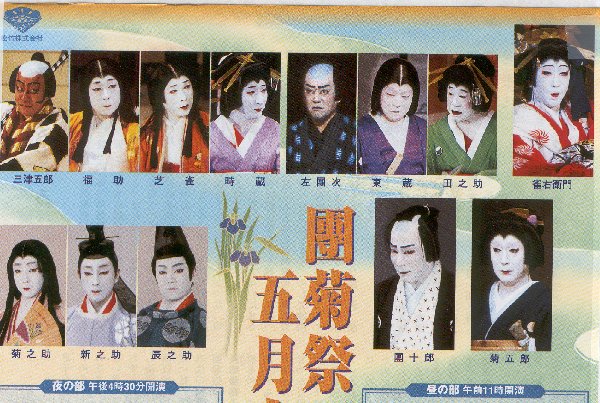

After dinner, we are bundled into the bus and shipped off to the kabuki theater on the Ginza, which looks ancient but was restored after its destruction in World War II.

One can readily discern that people are fanatical about the show: they are dressed to the nines, with some ladies in kimonos. A boxed meal at the theater can be had for about forty bucks. This is an upper-class treat. I guess we’re not upper-class, since our seats are on the third level, which is in the nosebleed section and affords an awful view unless you’re in the front three rows. We are not in the front three rows. I cannot imagine what the view is like from the fourth level.

We are given earphones and a tape recorder that provide us an English narration while the drama plays out. The makeup and costumes are lovely, and it is hard to believe that all of the roles—male and female alike—are portrayed by male actors. (There was a time when women played female roles, but a certain shogun outlawed this based upon some moral argument or other.)

The play treats of some samurai ("temple

man"  , reflective of his honored socio-religious status)

who was tricked out of a treasured heirloom sword and ends up

murdering ten people at a ryokan (Japanese teahouse). The

show is so dreadfully boring that I consider slicing the webbing

between my toes with a linoleum knife for amusement. Now, are my

ears tricking me, or is some guy off to the left and behind us

making peculiar noises? In fact, listening more closely, we find

out that the gentleman—intense-expressioned and immaculately

dressed in a black suit—is shouting "Yomotoya!"

It appears that, much as we would yell "Bravo!" the

Japanese yell an actor’s name when his part is about to

begin or whenever they perceive he is doing an excellent job. (In

actuality, it is his stage name—often the name of a famous

actor from olden days, suffixed with a Roman numeral—not his

real name, as the taped sound track revealed that the actor

was "John Smith yago Yomotoya VII" or some such.

Imagine, for a moment, if Keanu Reeves went by the stage name

"Laurence Olivier XXVI" and we shouted

"Olivier!" whenever he entered the stage.)

, reflective of his honored socio-religious status)

who was tricked out of a treasured heirloom sword and ends up

murdering ten people at a ryokan (Japanese teahouse). The

show is so dreadfully boring that I consider slicing the webbing

between my toes with a linoleum knife for amusement. Now, are my

ears tricking me, or is some guy off to the left and behind us

making peculiar noises? In fact, listening more closely, we find

out that the gentleman—intense-expressioned and immaculately

dressed in a black suit—is shouting "Yomotoya!"

It appears that, much as we would yell "Bravo!" the

Japanese yell an actor’s name when his part is about to

begin or whenever they perceive he is doing an excellent job. (In

actuality, it is his stage name—often the name of a famous

actor from olden days, suffixed with a Roman numeral—not his

real name, as the taped sound track revealed that the actor

was "John Smith yago Yomotoya VII" or some such.

Imagine, for a moment, if Keanu Reeves went by the stage name

"Laurence Olivier XXVI" and we shouted

"Olivier!" whenever he entered the stage.)

I manage to convince Cheryl to leave after an hour of this

torture. The subway ("earth below iron"

![]() —that is to say,

"underground rail") fare card machine

is confusing, but a guard rushes over to help us. My problem was

that, after consulting the Japanese-only map to calculate the

fare and then depositing the requisite coins, I was distracted by

the wrong buttons when I should merely have pressed the button

that displayed in red LEDs the ¥170 that I had fed into the blessed

machine. We believe we need the Hibiya line (or is it the Toei-Asakusa

line?) bound for Daimon, but when an express train (kyuko, literally, "hurry go"

—that is to say,

"underground rail") fare card machine

is confusing, but a guard rushes over to help us. My problem was

that, after consulting the Japanese-only map to calculate the

fare and then depositing the requisite coins, I was distracted by

the wrong buttons when I should merely have pressed the button

that displayed in red LEDs the ¥170 that I had fed into the blessed

machine. We believe we need the Hibiya line (or is it the Toei-Asakusa

line?) bound for Daimon, but when an express train (kyuko, literally, "hurry go"

) happens along, the guard gestures toward its doors

and yells, "Daimon! Daimon!" at us, so we board the

train, presently finding ourselves at Daimon station, one block

from our hotel.

) happens along, the guard gestures toward its doors

and yells, "Daimon! Daimon!" at us, so we board the

train, presently finding ourselves at Daimon station, one block

from our hotel.

Back at the hotel, I’m ready to commit murder after such

a long day without decent sleep the preceding night. We decide to

watch the sumo

championship (basho)

on channel 1. What a fascinating game: the referee, or gyoji,

who looks like a sorcerer in his medieval court costume, waves a

fan most delicately to signal to the two rikishi ("force scholar"

) when to collide.

The winner is signaled by another effeminate movement of the fan,

after which the referee hands some twisted black cords to the

winner—who then leaves the ring and hands the cords to a

second official. I have no idea what the significance of all that

nonsense was. I won’t say much about sumo here, since there are many

books about it, other than to say that the rikishi get so

fat by eating massive quantities of chanko-nabe ("everything stew") and having their intestines

massaged by experts.

) when to collide.

The winner is signaled by another effeminate movement of the fan,

after which the referee hands some twisted black cords to the

winner—who then leaves the ring and hands the cords to a

second official. I have no idea what the significance of all that

nonsense was. I won’t say much about sumo here, since there are many

books about it, other than to say that the rikishi get so

fat by eating massive quantities of chanko-nabe ("everything stew") and having their intestines

massaged by experts.